OUT OF ONE WALL: POLIT-SHEER-FORM, 5 YEARS ON

| August 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 4

Polit-Sheer-Form, which marks its fifth birthday this fall, has been a steady presence on the Chinese art scene of these dramatic years. Coming together at regular intervals for debate and a trip or two to the bathhouse, Hong Hao, Leng Lin, Liu Jianhua, Song Dong, and Xiao Yu ponder what it means to belong to the last Chinese generation, born in the mid- to late 1960s, who remember actually existing socialism. LEAP editor Philip Tinari sat down with Polit-Sheer-Form “secretary” (and Pace Beijing president) Leng Lin over lunch in 798 last month.

PHILIP TINARI (PT): Can you first talk about the origins of “Polit-Sheer-Form”?

LENG LIN (LL): Back in the 1990s, when I was still working at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, there were fierce debates going on in the academy and the art world in China over multiculturalism. To me it was obvious that these debates, which were largely Western in origin, did not account for the distinct subjectivities produced by the different social frameworks of socialism and capitalism. But at that time China wanted to “enter the world” and the desire to contribute something to the global conversation was quite strong. In the previous era the emphasis was on using socialism to attain communism and save the world; we had a Marxist-socialist view of the world and this meant certainty in the direction of mankind. But what did China have to offer the world in the 1990s? For me it was less about recognition and identity politics than we could actually contribute, and that seemed to be a consciousness shaped by these earlier political experiences. Collective idealism dies hard after all. So in 1996, I held a conference at CASS with sixteen artists attending, and this idea emerged to do an exhibition on the new socialism.

PT: So the project was actually in planning for nearly a decade before it finally appeared in 2005?

LL: Yes. We had our conference, but the exhibition never came to fruition. Making exhibitions in China back then was not an easy proposition. There were no venues, and no money. Later, I moved to Berlin. Song Dong was always passing through, and we would discuss. He was one of the artists included in that original conference. In Berlin, I just happened to see an exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof about the idea of the “Wall,” a ten-year retrospective of art from Eastern Europe [“Quobo: Kunst in Berlin 1989-1999” ed.] It left a deep impression, because I was already thinking in that direction. I tend to think a lot about how in China, some things have changed but others have remained the same. I took a bunch of notes at that exhibition, and never let go of the idea.

After I had started Beijing Commune in early 2005, I had the opportunity to program it, and that was exactly as the market was beginning to take off, so the idea of doing something against the market seemed interesting. Somewhere around that time, all conversation turned to who was selling well; artists stopped talking about art. With the onset of these commercial interests, artists became more and more individualized. I thought it was important to bring back the collective, to interrogate its true value, to ask why so many collectives had become so weak. Although I had a gallery, there were no funds to work with, so I approached Uli Sigg, described the situation, why we wanted to do this. I stressed that Chinese art could not just move in this one market-driven direction; I told him I wanted to put the brakes on. He agreed with the idea and pledged his support.

PT: So presumably by that time the members of Polit-Sheer-Form had already come together. How did that happen specifically?

LL: In May of 2005, when the first exhibition opened at Beijing Commune, I was already thinking ahead to the third. I had separate discussions with Song Dong, Xiao Yu, Liu Jianhua, and Hong Hao. We knew we wanted to do something together, but weren’t sure what. And we didn’t really know each other very well, so our first meeting, in the gallery, was quite awkward. It was the middle of July. I set out five chairs. There was a round of self-introductions followed by a lot of silence. Everyone had come with a sense of enthusiasm, but no one knew what to say. Then we all went to dinner, and people loosened up.

PT: You had different a different relationship with each of the others. You knew them through different channels, then brought them together. Are you the center of the group?

LL: We are just five guys, there is no center. I met each of them very early on; I was the only one who knew every other. But we came together with the express purpose of doing a collective exhibition, explicitly devoid of individual style. As we sat there talking that first night—we were on the roof of Song Dong’s house near Houhai, after dinner— someone, I forget who, mentioned a place called Nanjiecun, in Henan province, where socialism is still actually existing. We all got very excited, hopped online, looked it up, and decided that very night to take a trip there together. We hatched other plans to visit factories, villages, North Korea. It was never clear exactly what we would do in these places, but we went. And on the road we would eat together, conversing the whole time. In these discussions we came up with a new concept: “the politics of pure forms,” or as we later called it in English, “Polit-Sheer-Form.”

We are the post-Cultural Revolution generation; we were too young to be conscious of the brutality of the social change going on then, we just knew there were always meetings to attend, a collective life to be lived. Collectivity is often ignored, but we still hanker for that collective life; you see it in the way Chinese of my generation are so happy to eat in large groups. It has to do with being born in the 1960s. The form of the political movement retains a strong hold on us, albeit entirely stripped of political content. Chinese society since 1949 is defined by its political nature; this is a special characteristic of our nation. We wanted to ask what forms can be extracted from these politics, and if they were of any value.

PT: What do you mean by introducing the word “sheer” into this idea of political form?

LL: “Sheer” refers to form. Political forms generally have content, but this form of ours does not. We have no real goals, political or otherwise. Making an exhibition is not even the important thing; our goal is just to spend time together, to converse and debate, and thus to come to our own feeling of history. Developing this shared consciousness became a goal in itself. We eat, watch football—the point is that we don’t have to go it alone, as a collective we enjoy things that get left out when the emphasis is entirely on individualism. Most artists and art groups pursue “perfection,” but we believe that this is futile. As a group we are trying to escape, not embrace, utilitarian ideas. When we come together we forget everything, and suddenly our minds are clearer, we are willing to share ideas, which continue to brew among us.

PT: The first exhibition you did together—simply building a big blue wall in the gallery space—how did that come about?

LL: We took a picture together at a steel mill in Beijing, as a record of our trip to this factory. When we took it, we didn’t feel anything at all. Later on, one night after dinner, we looked at that photo using a projector and realized that there was a lake in the frame. We blew it up and realized that the “blue” of that lake suggested no direction, and thus that it was totally abstruse. There was nothing you could say about it, no information you could attach to it. So we built a wall and covered it with this image. It contained so many different meanings. We wanted to emphasize its literal presence, not the Cold War metaphorical connotations of the idea of the “wall.”

PT: In 2008, the group did its most ambitious exhibition to date, called “Library.” Can you talk a bit about the ideas behind that exhibition, and where it fits into the group’s practice?

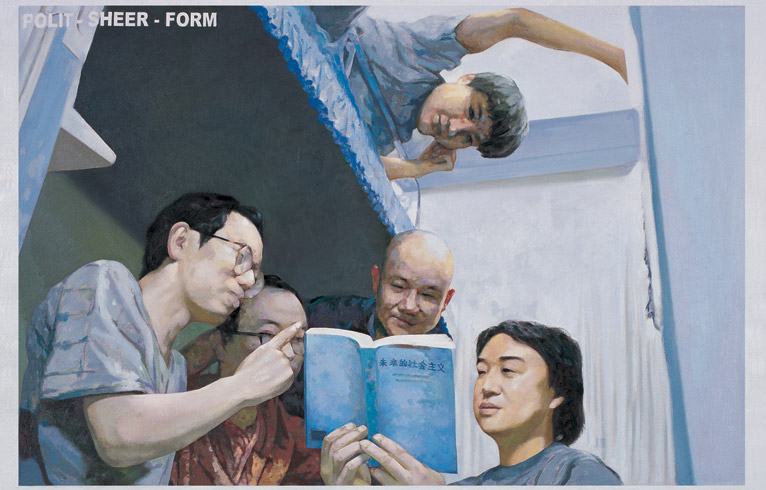

LL: As I mentioned, we had one early experience of traveling together to Nanjiecun, the site of still existing socialism. Obviously this implies a lot of successes and failures, and we were interested in looking at those. We went by train, and we brought books on the way. We had this idea then to all read the same book and use it to debate questions of politics and society. We settled on an older volume edited by the Central Translation Press called The Future of Socialism, which included articles mostly by foreign leftists and Communist leaders, such as Gorbachev. The painting exhibition we did in 2007 actually included an image of us all reading this book on the train. That was not the only time we read together. Another time we had a discussion with [MoMA curator] Barbara London’s husband, a scholar who ended up sending us a whole pile of books including Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations.

The “Library” exhibition grew out of that experience. We printed ten thousand blue books with “Polit-Sheer-Form” and a unique edition number on the spine, and placed them on twenty-five blue bookshelves. Every page in every book was blue, but the blue was very explicitly printed; we did not just choose blue paper. We dubbed this blue, the same one we used in our first work, Only One Wall, “Polit-Sheer-Blue.” Blue for us represents a fathomless, unending exploration. Another valence is that in China we used to talk about “oceanic civilization” (haiyang wenming)—i.e. the world outside China—in opposition to our own “continental civilization” (dalu wenming). The former represented openness and progress. So using this words that are used directly in Western languages. Their meter and cadence is not far off of “Polit-Sheer-Form,” so somehow we came up with this idea of a slogan: “Tofu, Kung-Fu, Polit-Sheer-Form.” This inspired us to make a film, a commercial really, as a way of explaining this funny slogan. It was propaganda for a meaningless idea, but it also looked at the relation between the local and the global, and so it had a lot of subtitles.

PT: After working together for five years, do members of the group ever feel they have to compromise or give up ground to others in the name of the collective?

LL: We don’t compromise; compromise is too painful. We just appreciate. In the process of debate, we discover each others shortcomings and strengths, and use those.

PT: You mentioned the experience of your generation, defined by the psychological aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. Now that this generation has more or less assumed power throughout the country, do you think that there is a shared generational consciousness manifest in the society at large?

LL: I think so. And I think there are elements of this shared consciousness that need to be activated or awakened, because often they have been repressed by the swift development of the country. The five of us attempt to awaken these ignored things for each other. We know that there is something collective beneath our individuality.

PT: Does this make for a sort of anxiety?

LL: I wouldn’t quite call it that. There’s no time for anxiety; the society is developing too quickly. But we are not looking to discuss the problems of a generation, we are more interested in finding particular elements of our collective experience, perhaps those that have been forgotten and repressed, and seeing what we can draw from these that might be relevant to others—of our generation, throughout China, and in the world generally.

PT: And for you that is mainly the idea of the empty rhetorical and ideological forms left over when the content has been evacuated?

LL: Yes, and for us the best way to get at these forms is simply by spending time together, eating, drinking, and goofing off.