GREAT PERFORMANCES

| October 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 5

“Great Performances” looks like an art historical exhibit. Curator Leng Lin puts together works derived from a variety of fields—including video, installation, photography, painting, and performance art—in order to depict a subject that, in turn, transcends all of these categorizations: the “performance” factor that can be extracted from each of them. He uses this subject as a means of probing the nature of art practice since the nineties, and invites a certain degree of public discussion in doing so. This goes especially for the art market: at a time when the Chinese contemporary art market still places importance on the differentiation and segregation of media, and conservatively tends towards easel painting, the fact that a gallery of considerable influence has mounted such a self-consciously problematic exhibition unavoidably gives rise to certain expectations.

As for its relevance to the public, the popularizing effect of an exhibition like this cannot be ignored. Budding art collectors of this century quite possibly do not understand, nor really care about, what artists were up to in the nineties. But now, they can see that artists such as Zhang Huan, who has since become a fashionable new favorite, was only one member of a group of pioneering artists in the nineties, even if he has since been made into a star. Only with this kind of historical perspective can we clearly see what artists were doing and clearly discern their value, rather than their price; in reality, Zhang Huan’s best work to date remains To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond, (featured in this exhibition), and yet even though his subsequent works arguably reveal no further artistic growth, the prices assigned to them would speak differently.

In a short foreword to the exhibition, Leng Lin elevates “performance” to the significance of a cultural subject. Here, “performance” is no longer merely an artistic language or method; it is emblematic of the self-consciousness constituting contemporary art today. It appears as if the line of critique formulated by Leng Lin in the nineties has not changed. “Performance” is related to self-revelation, an “It’s Me” (to borrow the title of Leng’s pathbreaking 1998 exhibition) attitude. It is associated with a kind of construction that positions the artist as a subject in the context of history and reality—a kind of construction that will play a foundational function in Chinese contemporary culture. However, if the notion of “performance” can indeed assume significance of this immensity, if it can serve as such an overarching subject heading, then where is the limit? At the point where an overuse of pigment can turn into “the performance of pigment,” what will be left that cannot be summed up as “performance?”

In light of this, it seems advisable to apply the word “performance” with caution, and to do the same when assigning it the modifying adjective “great.” Indeed, Zhao Bandi demonstrates this degree of superlative in performance. Everything Zhao does becomes performance. His artistic practice is indistinct from his real life: performance is the self, and therefore the self is performance. This is a form of thorough self-definition; it is a “self-heroism,” radical to the point that no one knows what he is doing, other than constructing a symbol of self-image.

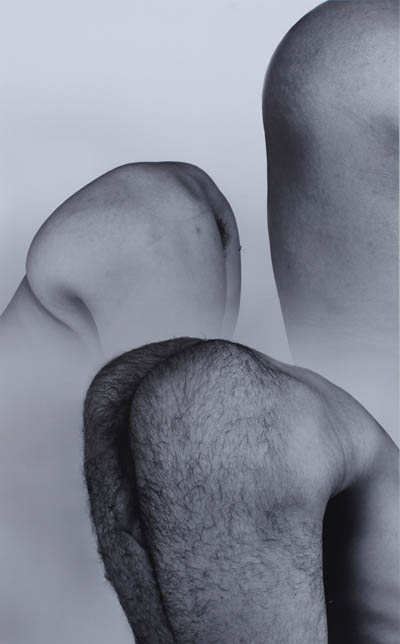

Of course, Zhao Bandi is an extreme case. “Performance” is more often an artistic medium unto itself. For He Yunchang, it is a way to add intensity and difficulty to creative work, or to use Liu Xiaodong’s phrase, a way to hinder habit forming. Here, “performance” is not about playing dress-up; it is the elimination of pre-fabricated falsehoods through active enactment, with the aim of critiquing the unconscious performances of social “reality.” “Performance” is about revealing and embodying the features of subject, body, consciousness, medium, and so on, and leaving the audience with a true sense of their existence. Bao Dong