WANG TAOCHENG: I TAKE MYSELF VERY SERIOUSLY

| October 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 5

In the China Pavilion of the Shanghai Expo, the image of Qingming Festival—the twelfth-century work of Zhang Zeduan of the Northern Song—is projected onto the wall. By now, this famous painting has played itself out as a popular, massive, dynamic ink creation—throughout the course of Chinese art history, Zhang’s depiction of the Bianjing city marketplace eight hundred years ago has served as a classic portrayal of ancient city life; more often than not, it has been the archetype that people of each period have sought out in their own recollections. But circumstances change with the passage of time, and the indubitable obsolescence of this grand scroll depiction of the northern folk of old has been exposed by the work of a contemporary artist in the present Shanghai.

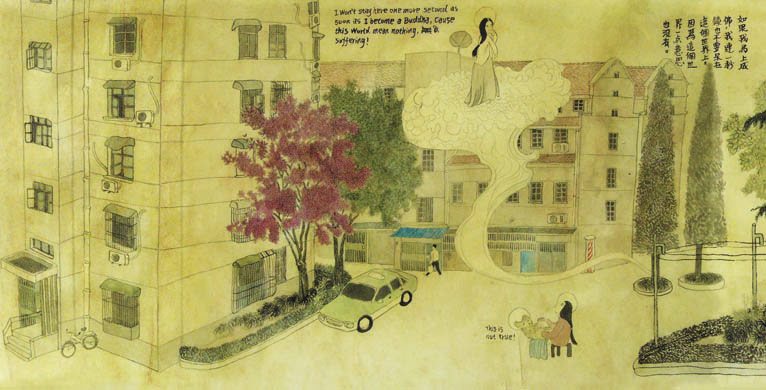

The soul of Shanghai is under the Expo’s many national flags, in an alleyway—this is the place where Wang Taocheng has settled. The artist’s hometown, Chengdu, is a place rich with the aura of an old city marketplace, where neighborhood gossip spreads from one street corner mahjong table to another, and where residents take themselves more seriously than anything else. As far as they are concerned, their little town-bound existence is a very serious matter, and infighting schemes and intrigues classify as soul-stirring events. Though born in the eighties, Wang Taocheng is skilled when it comes to picking up on these critical trivialities; whether out of the plot of a film or the reality of neighborhood trifles, he can take a tableau of petty arguments and transform it into the squeakings and squawkings of the lively original scene. His use of ink gives his paintings even more of an old-fashioned sensibility, one that surpasses his age. The medium also gives each scene that feeling of that humidity so unique to the south, in such an intimate way that viewing becomes traveling.

Wang Taocheng’s own image appears in each of one of his creations—his handlebar mustache or his ambiguously feminine face occasionally ride along the clouds and mount the mists with the charm of a bodhisattva in a Sui or Tang mural. It is from this position of omnipotence that he flies from window ledge to window ledge in his paintings, poised in his voyeurism and earnest in his story-telling. He positions himself in thin air, extending his senses as far as possible beyond the self so as to learn about the objects of his work; Wang plays a role that transcends male or female, reality or fantasy. People who focus in on the trifles do not care who they are themselves, they just stick their noses into the lives of others. The ability to sneak into everybody else’s life, then, becomes the ultimate kind of transformation.

In the dim gallery, the viewer can take a pushan (palm leaf fan) and a flashlight from the table, and instantly assume the role of an idle outsider poking around after the latest news. Gossip is spread across the table, and rising out of the pile are the twelve seasoned town gossip providers on whom curious people depend. By the dim light of flashlights it is actually possible to examine, and in turn to become the person who lives to converse.

Presumably, Zhang Zeduan also had a deep reaching understanding of the trifles of the city marketplace when he painted Qingming Festival. Choosing not to depict that scene would have meant not doing enough to express the joy of its trivialities. Whether it is Zhang Zeduan’s north or Wang Taocheng’s south, ancient or contemporary, both are about the refreshing experience of strolling through the streets. The beauty of the Chinese city exists most in those public spaces where people can enjoy one another’s lives—and where their lives and the lives of those around them are watched by a transparent person who represents the whole event, riding the clouds, mounting the mists, and spreading his wings. Li Qi