ALTERNATIVE SPACES, ALTERNATIVE STRATEGIES

| December 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 6

A particular and much remarked upon characteristic of the Chinese art scene is the hyper-commercialized, gallery-based system. By and large an import from the West, the Chinese gallery system over the last ten years has swiftly matured, serving as an important point of connection between Chinese artists and the outside art worlds. For better or worse, the galleries and the commercial systems they embody dominate the Chinese art world, with the phenomenon of discrete art districts (such as Beijing’s 798 and Caochangdi, or Shanghai’s M50) developing as the most visible manifestation of a state-sponsored recognition of the economic and cultural power of contemporary art.

However, this development has seemingly come at the expense of critical engagement and relevance to its greater social context. There is a great risk of failing to move beyond or advance due to this juggernaut of industrialized contemporary art. This situation seems to be a symptom of China as an active but juvenile participant in the international art scene: the development of a mature art system incorporating a productive sense of self-criticism has simply not had time to develop here.

And yet a number of artists and organizations have looked for ways out of this impasse. By consciously straddling the divisions between the art organization, artwork, and society, they play with the same concerns but push meanings and boundaries in unlikely directions. Given their positions of relative and flexible autonomy from the systems they are addressing, they are also able to critique without suffering fatal consequences. In a certain and very real respect, their capital is intellectual and social rather than financial, and if they are inclined to critique the gallery, museum, artist or society by playing out its roles, they are given more leeway in that respect.

These “spaces”—although only some of them have a tangible, permanent space—are putting methodologies into place that are in dialogue with and in criticism of the existing systems. They are a set of people and organizations who are fully aware of how their activities sit in relation to the less critical sectors of the (Chinese) art world, and hence serve up work and actions that try to break through the issues and problems arising from such an art world and the larger society of which it is a part.

Although suitable as a point of departure, “alternative” is a misnomer for these spaces. That word is commonly understood to be “in opposition,” but these artists and curators think of it as “in addition.” They are not trying to be “alternative” for the mere sake of difference, but to go beyond these things they find fault with, one of which may be the very concept of “alternative” itself.

For instance, the use of this term is not necessarily about anti-commercialization per se, but more specifically in confrontation with the kind of uncritical commercialization of the current Chinese art world. These organizations are an “addition” to the forms of galleries that seem so inflexible: unable to deal with certain types of work, only allowing certain channels and forms of activity within their walls.

A common tactic is for them to ostensibly position themselves outside the gallery system while maintaining a connection to it for their own purposes; dipping into and out of the various art structures as they see necessary. In many cases galleries, formal exhibitions, and traditional art structures are simply unnecessary to them. Not actively “anti-,” but happy to pick and choose moments of inclusion and exclusion wherever possible on their own terms. Their actions are often characterized by a sense of subtlety and invisibility as a way of countering overbearing systems and structures.

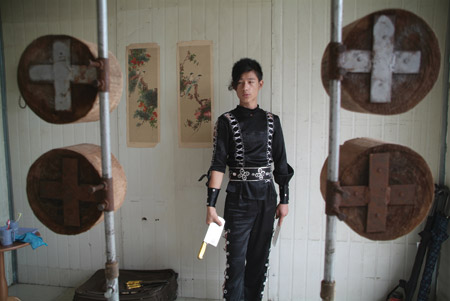

Just to list a few examples: HomeShop brings shop-front practices to the hutong context and promotes social activities that occur near its location in a local neighborhood setting, thereby “crystallizing” events out of daily activities. The Donkey Institute of Contemporary Art brings the art context directly to a moving public, redefining it in a mobile format. Artist Chen Xinpeng’s tent for last year’s mobile “Cou Huo” exhibition organized by Red Box Studio also carries his activities to non-art areas, with structures to facilitate pop-up shows and spectacular practices, open to art and non-art activities. Ma Yongfeng and his “forget art” collective rework ideas of minimalism and conceptual practices, playfully confronting institutionalized art formats in China, including a recent exhibition in a bathhouse. And Emi Uemura opens up discussion in the specific context of China’s food and agricultural realities, taking on social concerns in the particular situation in which she finds herself.

Talking to these artists and curators, recurring motifs are their practices as facilitators and platforms for the art-making process—the suggestion being that these are difficult or impossible to find with existing institutions and methods. Behind these activities lies a looming feeling that art is now increasingly recognized and naturalized as a production system, on the same level as any other system of production, and not automatically privileged. They are wary of these systematic forces of commoditization and commercialization. They do not hold Art in such reverence as in the past, but take it rather as a domain to be only selectively employed.

These methods and practices are common in the international art historical context. They rehearse fundamental issues with the privileged position of art as seen in strands of Western art history. But where they transcend these is in the artists’ relationship to the specific conditions in China—they are original in this respect. In China, these positions are relatively new approaches to making art, and in this context new possibilities for the future of art are created, possibilities which will need to be addressed by these artists and their peers. These possibilities do not simply play into existing systems, and by their immateriality or impermanence act to gain space without production as such.

The works can seem to be distancing, maintaining a relationship which does not fully subscribe to or get subsumed by any particular end. This idea (of the semi-formed action with no particular aim or expected conclusion, which has a political inflection simply in its avoidance of common forms of political activity) seems to be particularly appropriate in this situation defined by appearance. And, as has been seen in these practices elsewhere, it must be forever delayed in its path to production—its futility is potentially unending, though “delay” and “futility” are central to its potential for action.

The spaces profiled in the following pages play a vital role in developing art systems with larger implications, starting at the level of localized production. The production of these “alternatives” addresses perceived problems or deficiencies in the system. Their existence is an important aspect in the critique of art and the critique of its dissemination. Experiments and new forms of presentation are important to provide depth and perspective to the art world and to take it away from an over-reliance on a limited and limiting way of dealing with art and the locations in which to experience it. What might be called a “healthy art ecosystem” supports these multiples avenues of experience, providing the checks and balances that prevent one section of the system from presenting a distorted vision of art and its value, as has become the case in the Chinese art scene.