BACK IN THE DAY: ALTERNATIVE SPACES IN THE EARLY YEARS

| December 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 6

CHEN HUI-CHIAO

Taipei/IT Park

Initially, the motivation behind IT Park came from the artists and students who would return from studying abroad full of thoughts and ideas, but without a place to unleash their creativity. At the time, there was virtually no space for modern art exhibition or performance. I wanted a space simply to meet and discuss with others, a space where everybody could bring out their yet unripened ideas and artworks, inspire one another, and probe all the possibilities art affords. Using the name “park” was my attempt at relaying its relaxed and open nature.

Since its inception, IT Park has been concerned with creating a “spiritual place,” rather than with how to socialize art. We’ve never poured much energy into so-called strategic problems. We are simply persistent in what we do.

In 1994, we turned the four year-old foyer café into a bar. As previously mentioned, “discussing art” was our initial motivation, which grew out of our own experience: we often went to other spaces’ exhibitions but would never stay long, as it was never possible to strike up any interaction with the actual artists. But if you have a bar or café, it changes everything; that kind of interaction and more becomes possible. The bar stayed open for six years, during which visitors included artists, critics, designers, celebrities and all other sorts of people from the in-crowd. Here in Taipei, IT has always been a fashionable space. And although it was so immensely popular, this localized excitement and enthusiasm for art eventually thinned out, only to be replaced by high-density international information flows.

As an alternative space, IT Park early on was, relatively speaking, marginal and atypical. This was especially true for the purity with which it attached importance to artists’ creative attitudes. Entering our second decade—now, the bar has been demolished, and we’ve already encountered every sort of operational difficulty—IT Park’s importance to the development of Taiwanese contemporary art has gradually revealed itself. Following the art world’s trend towards globalization, IT Park evolved into an important channel through which international art professionals would come in search of new artists.*

Each of these periods has been important for IT Park, as each represents the maturation process of different generations. Any single exhibition or artist can represent the standpoint of IT Park, which is a space where the artist calls the shots.

From IT’s founding up until today, our greatest source of exasperation has been the temporalization of space, and the spatialization of time. The emergence of transient things and artistic symbols here all force us to ponder, to learn, to seek an explanation for the essence of meaning. You can’t necessarily stand at the peak of an era forever, but nor can you abandon it, either.

*This paragraph is in reference to an essay by Jason Chia-Chi Wang, “The Alternative Contemporary Art Space That Can’t be Replaced—In Commemoration of the 20th Anniversary of IT Park.”

Chen Hui-Chiao is an artist and the founder and director of IT Park.

INTERVIEW: Aimee Lin / TRANSLATION: Michael Einar Engstrom

Chen Tong

Guangzhou/Borges Libreria Institute for Contemporary Art

At the end of 1993, Borges Libreria was founded on the campus of the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, with the idea of providing an outlet for the dissemination of contemporary culture. As an artist, not a businessman, I saw the bookstore as a work of art. Like the semi trucks we see hauling other, smaller cars on the highway, its actual function is to distribute other works.

Unlike other bookstores that on occasion held cultural events, our motivation for doing so had nothing to do with increasing book sales, nor with bettering our reputation. We held events for the sake of holding events. And so, when my economic circumstances changed in 2007, the artistic function of Borges Libreria became independent from the bookstore itself. Now, as the word “contemporary” is ever more wonderful and fashionable, we have changed the name to “Borges Libreria Contemporary Art Institute.” Publishing is our main task. We don’t hold many exhibitions, and when we do, it’s not to promote artists, but to give those around us the right kind of influence. We use literary methods to do art, and artistic methods to do literature: narrative becomes inevitable, and the conceptual becomes necessary. Simply put, that’s all there is to it.

As lovers of the French novel, we planned to publish many works from the French publishing house Editions de Minuit. Our publishing work is quite solid. On site, people can not only find interesting books, but they can also frequently encounter writers, such as Jean-Philippe Toussaint, who collaborates with us on a number of fronts, including filming movies. Recently we held a special event, Robbe-Grillet et l’Art, with the objective of rejecting the re-emergence of modernism. The danger of such a re-emergence is that it turns art into a tool, and even assumes the face of contemplation. We discovered this tendency in contemporary art, and felt that Robbe-Grillet’s work aimed to address it.

In the so-called artistic ecology of Guangzhou, we have always played a unique role. We are not under the influence of any organizations, nor do we have the power to influence others (indeed, we are the only ones to actually call ourselves an “institute”). Our relation to this city is not particularly strong, yet we have, to a certain extent, contaminated its personality. As long as the city tolerates us, and we rely on ourselves to think and analyze, we will continue to develop with quality as our priority.

Nothing about the work we do or projects we run has anything to do with the contemporary art market, but at the same time, we don’t spurn any form of commerce. Nowadays, we are more cautious about choosing our endeavors than we were in the past. At the very least, we ensure that a project’s corresponding publication has value, and that the corresponding dialogue is deep and meaningful. In people’s eyes, we are doing the same things over and over, to little or no effect. However, we find joy in this, in “obtaining half the result for twice as much effort.”

Chen Tong is an artist, writer, and founder of the Borges Libreria Institute for Contemporary Art.

INTERVIEW: Shen Ruiyun / TRANSLATION: Michael Einar Engstrom

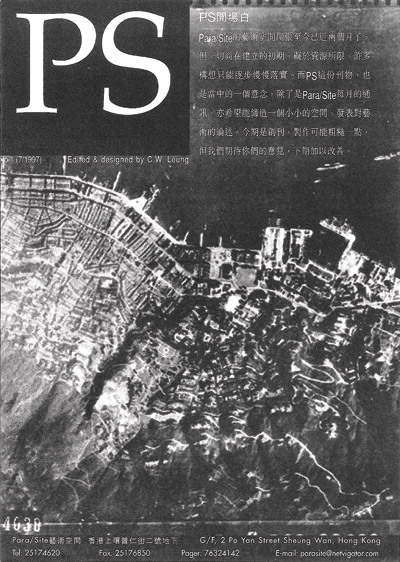

Leung Chi Wo

Hong Kong / Para/Site Art Space

Spontaneously organized and founded by artists in 1996, Para/Site was originally intended to give artists a space to create and exhibit their works freely. At present, Para/Site’s purpose is to promote Hong Kong contemporary art by exhibiting it alongside international contemporary art. In 2000 Para/Site was officially registered as a non-profit organization, which by law required us to establish a board of directors. At the beginning, the board was composed of artists and friends from cultural circles, but in 2004 we added professionals from all sorts of fields, including architects, educators, and collectors. The exhibitions in Para/Site are all organized by professional curators with a term of three years. It is in preserving the diversity of its staff that our space retains its vitality.

Early on, Para/Site was not run in a professional manner, but it was nevertheless flexible. We took every opportunity we had and embraced it, as everybody’s connections were different and thus engendered different effects. Para/Site member Ho Wai Chi was originally in environmentalism, having worked for Greenpeace; his knowledge of non-profit organizations and their management contributed greatly to the smooth functioning of Para/Site. My interest in international exchange and in networking has broadened a bit, which has had an impact on some of our projects. In short, multi-faceted collaboration has enriched the dynamics of our organization.

Sponsored by Hanart TZ Gallery, our satellite space Para/Site Central is the smallest art space in Hong Kong, at about the size of a bookcase. While it might not function well as a space for exhibitions, we stressed its flexibility—as far as creation goes, the space is neither good nor bad. Living in Hong Kong, we place a great focus on intimacy with space.

Decision-making at Para/Site has varied with time. At the beginning, artists made decisions on their own. Later on, the artists voiced their ideas, and others carried them out. Artists stepped back from the front lines to play strategic roles on the board of directors. Planning and logistics are now executed by a group of professional, passionate, socially committed individuals from all levels of society. As an artist, I feel that I have grown up with Para/Site, and that my career has developed thanks to its presence. At the end of 2003, we artists had become so busy that we considered closing the space down. However, we realized that through its existence alone, Para/Site could be useful to many others. We realized that it could continue to act as a valuable source of information for more and more artists, and give them quality conditions in which to exhibit their work. And so, we decided that Para/Site should go on, but in the form of a non-profit, with a professional director. When a space undergoes its growth process, there’s really nothing bad or good to be said. It’s better to say, simply, that at different stages, it does different things.

Leung Chi Wo is an artist, university professor, founder and former director of Para/Site.

INTERVIEW: Shen Ruiyun / TRANSLATION: Michael Einar Engstrom

Davide Quadrio

Shanghai/BizArt Art Center

I am preparing to write a book about BizArt, but not all by myself. I will invite other people to contribute as well, to make an honest analysis of what, against the cultural backdrop of China, an arts organization really is. I feel very proud: after so much time, we are still the only organization that hasn’t sold a single artwork, nor have we ever asked artists to hand over works in exchange for holding exhibitions. Here in China, I believe that this kind of approach is pretty ruthless.

From 1998-2000, BizArt was just a temporary venue, without a strong sense for exhibition planning. In 1998, I met Hans van Dijk, who helped me think many things through. The next year, in 1999, we put together an exhibition of Gao Shiming and Gao Shiqiang’s work. 2000-2006 was a truly interesting period. In 2000, Zheng Guogu had a solo show, a very interesting exhibition of Lomography. And when Tehching Hsieh came to Shanghai, BizArt took him in, thus starting an artist-in-residence program. Likewise, we organized lectures for Fei Dawei just after his return from France. Funny to think this is all a decade ago already.

In 2001, Xu Zhen joined our team. We had a lot of interesting solo exhibitions. Thereafter, we started to work with academies abroad. At that time, it was awfully radical for a private Chinese organization to work with any major foreign organization. The itinerant “Homeport” project [which staged interventions in a handful of world cities including Shanghai] marked the first time that contemporary art made use of public space, placing works in Fuxing Park. Many artists, including Yang Zhenzhong, Xu Zhen, Song Tao, Liang Yue, and Ni Jun, had their first solo exhibitions at BizArt. Later on we started to hold exhibitions in other places in Asia, such as Korea and Thailand.

At that time we didn’t have a clear purpose; we simply wanted to do something with art. Another motivating factor was a desire to attract people’s attention, and show them that art isn’t only about painting and sculpture. Perhaps it’s a bit of an exaggeration, but I believe that if what you do hasn’t yet been done by others, then essentially you are helping push the times forward. But these thoughts are all in retrospect, whereas then we were just taking things one step at a time. Finances were a pain, then, too. During the SARS epidemic, we didn’t hold a single exhibition. We had no money left in the bank. Naturally, I was extremely worried. Then Xu Zhen called me, and proposed we have a meeting. At the meeting he suggested that we could rent out the space, leaving ourselves enough room for a small office. He maintained that we could all go find jobs to make ourselves a little money, but that the space itself mustn’t cease to exist, that it must go on. BizArt’s idealism early on has always played a big role in what we do. That held true all the way through 2004 and 2005.

After 2006, the Chinese art market got hot, and just about everything changed. I feel that our work has started to repeat itself, that it will never again be so forward-thinking.

Davide Quadrio is the founder and director of BizArt Art Center, and the founder of Arthub.

INTERVIEW: Aimee Lin / TRANSLATION: Michael Einar Engstrom

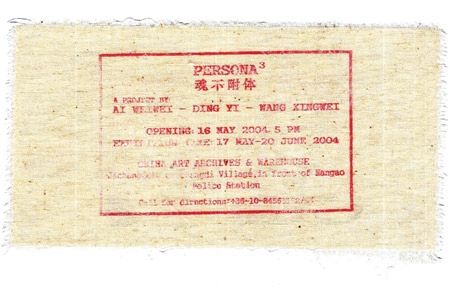

AI WEIWEI

Beijing/China Art Archives and Warehouse

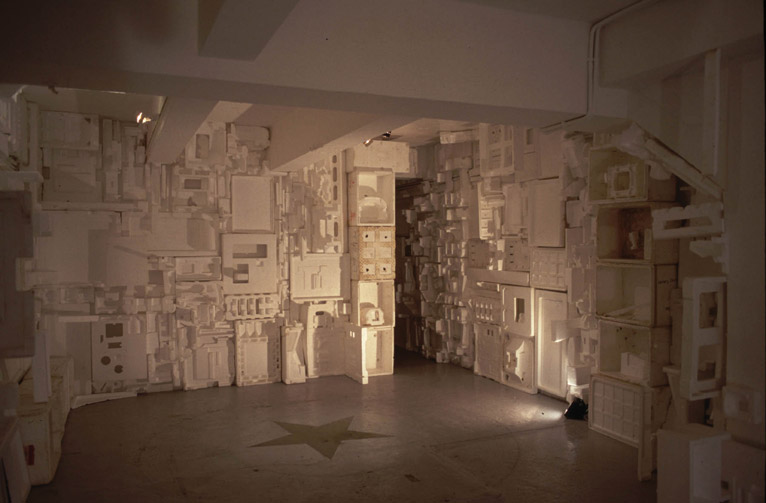

The Chinese art scene of the mid-1990s was depressed. There were no galleries or spaces for exhibitions. Exhibitions were held in hotel corridors and framing shops, or in diplomatic compounds. That was when Hans van Dijk (1946-2002) got excited about creating an art space, and we decided to do it together. We called it a “warehouse” because galleries had to be specially approved by the local public security bureau, but if we called it a warehouse we could skip this step. We found an old printing press in a village south of the Third Ring Road and created the first, biggest art space of its kind, like an American-style gallery.

We rented this space from the printers, but there was no cultural atmosphere to the neighborhood. It was on the city fringes, a total mess. But the space itself was nearly twice as big as the current CAAW, really beautiful, with high ceilings. I remember the first exhibition we held resembled minimalist painting. Lots of people came and they all asked us why there was nothing on display. People then weren’t used to looking at art in such a huge space. The problem was the neighbors, local peasants who would pile their trash at our door, a real mess. Later on I built a house in Caochangdi, and we decided to move CAAW nearby. We built a new space in 1999 and opened it in 2000.

In the beginning, it resembled a gallery, because Hans was still around and that was how he liked things. Every day he would go to the space and organize his files on different artists. But after he passed away, the burden of the space was on me, and I had no interest in doing a gallery. I only cared about making exhibitions. So we started working in a different way, just putting on exhibitions now and again. In 2003, we even made it into Art Basel.

We put on a lot of very good shows. No matter which metric you use—total number of shows, quality of the artists involved—we are at present the best art space ever to have existed in China. There is no comparison. Make a list of the exhibitions we’ve done: Wang Xingwei, Xie Nanxing, Zhao Zhao, and so on. They all showed with us early on. We work freely, however we choose. And because we don’t care about consequences, operating has never been a problem. Most galleries are designed simply to sell paintings, but that is so boring. In China as abroad, galleries really only exist for their openings; hardly anyone goes to them otherwise. I think this is a useless way of working. We have no need to maintain relations with collectors or any of that.

At present CAAW remains China’s freest, most independent art space. Its degree of freedom is precisely that of Chinese society in general; no additional compromises are made in the name of profit or to suck up to anyone. The space’s programmatic decisions are based on my and Hans’s judgment, and whether you like that judgment or not, you must accept that it is not based on financial interest. We don’t need to pretend to be a gallery and wait for people to come so we can receive them. Truth be told, we are a gallery that runs on a method of non-cooperation.

Ai Weiwei is an artist, activist, and the founder and director of China Art Archives and Warehouse.

INTERVIEW: Philip Tinari