FUTURE ALTERNATIVES: SPACES FOR NOW

| December 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 6

Arrow Factory

A spatial limitation forces a turn to other approaches.

It was the spring of 2008, and the city of Beijing was scrambling to prepare itself for the Olympic Games. Off the Airport Expressway, 798 and Caochangdi—infamous hubs of galleries and museums exhibiting contemporary Chinese art— were experiencing unprecedented growth. Meanwhile, in the center of the city near the Confucius Temple, taking its name from the hutong on which it is located, this 15-square-meter storefront, non-profit, alternative art space opened in a former vegetable stand.

Arrow Factory is fundamentally different from nearly every other art space in Beijing. On a daily basis, it is locked up, but the artworks can be viewed from the street around the clock. It does not make a big fuss about announcing the opening dates of its exhibitions, nor does it host any opening dinners. All tasks and costs required to sustain the space are shared among its three current members, Wang Wei, Rania Ho and Pauline Yao.

Stated with clarity and incision on the Arrow Factory website, “We do not sell anything. We subsist on small contributions from friends, colleagues and ourselves. We do not hold openings and we operate modestly, spontaneously and flexibly. Our mission is simply to provide an alternative; a different context in which artists can experiment with pushing the relationships that radiate outwards from the levels of the individual, the neighborhood, the urban, the region, to finally, the global.”

In the two and a half years since it opened, Arrow Factory has fulfilled this mandate. It acted as a testing ground for Kan Xuan in a series of installations under the working title Light, where all the artworks shown at the space were ideas that had not yet been entirely worked out by the artist. It involved local businesses, offering them possible alternatives for their everyday quotidian or commercial practices with Ni Haifeng’s solo exhibition “Vive La Difference.” It commented on the curious relationship between the local economy and the economy of contemporary art with Wang Gongxin’s sculptural video installation, It’s Not About The Neighbors, for which the façade of the space was transformed to visually imitate that of the pancake vendor next door. It entertained local residents with Nie Mu’s series of “televised” Chinese New Year activities under the title Channel Me, and Wen Peng’s One Man Theatre. Without enumerating every exhibition staged at Arrow Factory, the space’s programming has made clear to China’s art public that the white-cube model of gallery space is not the only one.

Local residents may still be baffled by the outlandish objects in and around the space that twig their visual landscape in the hutong. They might not feel threatened by the presence of Arrow Factory due to its non-commercial nature. They might not grasp the intentions of its founders to contextualize contemporary art production and experience in an urban milieu that also projects the global condition. Meanwhile, those artists who have participated in exhibitions at Arrow Factory have been forced to find another way to work out certain ideas and concepts within the physical limitations of the space—a limitation that has driven them to look into other approaches in their own art practice. Fifteen square meters is small, yet the possibilities it has opened up seem huge.

TEXT: Fiona He / TRANSLATION: Du Keke

ChART Contemporary

A public curatorial journey of temporality and mobility.

It is common for Americans to spend a Sunday afternoon going to an open house, where properties on the real-estate market are on view to interested tenants or owners. Behind this vision of one’s future residence is an embedded set of desires and expectations that drives one’s motivations, a desire that has yet to manifest itself, a desire with temporal qualities that lies open to all types of possibilities.

ChART Contemporary’s curatorial initiatives frame such desire based on a personal experience of apartment hunting in the spring of 2008. The sisters, Megan and KC Vienna Connolly have since embarked on experiments with emerging Chinese artists including WAZA, Du Yi, Cheng Guangfeng, Chen Ke and Huang Xiaoliang on journeys of temporality and mobility.

Unlike the “apartment art” of the early 1980s, where Chinese artists used their homes as venues to show their work and exchange ideas in the absence of art galleries or public art spaces, the site specificity in ChART’s curatorial initiatives not only seeks to emphasize the context in which the artwork is exhibited (and thereby to contribute to the meaning and artist’s vision through its milieu), but also to open up otherwise private spaces to the public, allowing for a perhaps voyeuristic peek into realms far beyond the normal art-world context. So far, each arranged marriage of artwork and context seems to have had a happy ending. In particular, Chen Ke’s A Room of One’s Own was especially compelling. Set in a room in the basement of a residence mostly occupied by foreign expats and the local nouveaux-riches, the path that led to the room where Chen Ke showed twisted and wound through dimly lit, humid underground corridors. The other rooms along this corridor were mostly occupied by migrant workers employed nearby. Near the end of this path, light rushes out from a simple room, about ten square meters, and containing a bed, a night table, a desk and a clothes rack. Every object in this room suggests a young woman and her dreams and desires for her future. Coupled by the unsettling sound installation of footsteps going up and down the corridor, the room led to a feeling of discomposure. Inspired by Virginia Woolf’s drive to pursue a writer’s career, Chen Ke relocated to Beijing in 2005 after graduating from Sichuan Institute of Fine Arts in pursuit of her career as a painter. The experience of being in this room—its title taken from Woolf’s canonical 1929 essay—highlights the artist’s determined vision for her career, while projecting the dreams of those who struggle to realize their dreams.

The temporary alternative spaces presented by ChART Contemporary are temporal manifestations bridging the artists’ vision and its curatorial interpretations of that vision, traversing the border of private and public spaces. At six o’clock in the evening of a particular open house, the installation comes down. This mere four hours of ephemeral existence of an art installation offers its audience a window of time and space to look at art from a different angle. Being alternative is as simple as challenging what exists by offering another way, be that through a fixed physical space, or physical spaces that manifest another conceptual model.

TEXT: Fiona He / TRANSLATION: Du Keke

HomeShop

Crystallizing events out of daily activities.

HomeShop was founded in the Dongcheng district of Beijing in 2008 by Elaine W. Ho and is currently on its way to a new home together with Fotini Lazaridou-Hatzigoga, Twist Qu and Ouyang Xiao. According to Ho, “HomeShop came out of my experience of living in China and fascination with the juxtapositions between public and private space, not only on a spatial level but also on social and economic levels. All our projects are determined by the possibilities offered by this space and its storefront, as a form for relating to the community and a lens through to the street outside.

“We’re interested in how people relate to one another on the basis of a commercial transaction, and how that commercial transaction allows for a certain public quality to a space that wouldn’t be there otherwise. It is the glass front that makes the juxtaposition between our living environment and the street bare and visible. I would hope that the commercial and the artistic could be rolled into one. That’s the tricky balance.”

HomeShop collaborator Fotini Lazaridou-Hatzigoga sees it this way: “Maybe the question is to stay more on the line, instead of having to take a position. There’s a sign over the door that says jia or “home.” Passersby are always puzzled by this and often think it’s a store. Some of them come inside wanting to look at our clothes, because they think they are for sale, or they start asking questions. It’s these kinds of everyday encounters and interactions from which we begin.”

HomeShop opened during the 2008 Olympics, a period rife with grand narratives and symbols. For Ho, the project was something of a reaction to this grandeur. “There were public screenings of the Games projected on the storefront,” she recalls, “as well as a reading group, field recordings, and other activities where I invited artists to come and do interventions on the street or neighborhood. A lot of our activities are time-based and event-based; they are ephemeral and very limited in terms of who can participate. So aside from the series we also publish a journal called Wear, which started from the very simple purpose of documentation, but as a reflection that can take the work to another form of thinking.”

Ultimately, the project raises questions of process, relation, and even education. As Ho notes, “I think it’s the difference between looking at an artist as a product maker—one who signs their name on their thing and sells it—versus as worker or researcher. Finding a balance between an artist’s project, coming out of certain initiatives and interests of ours, but also as a way of building a community. How much a community can be involved and how much it can come together without being over-organized; in one sense this can become a political question.”

TEXT: Edward Sanderson / TRANSLATION: Du Keke

Observation Society

Redefining artistic freedom with a low-cost alternative.

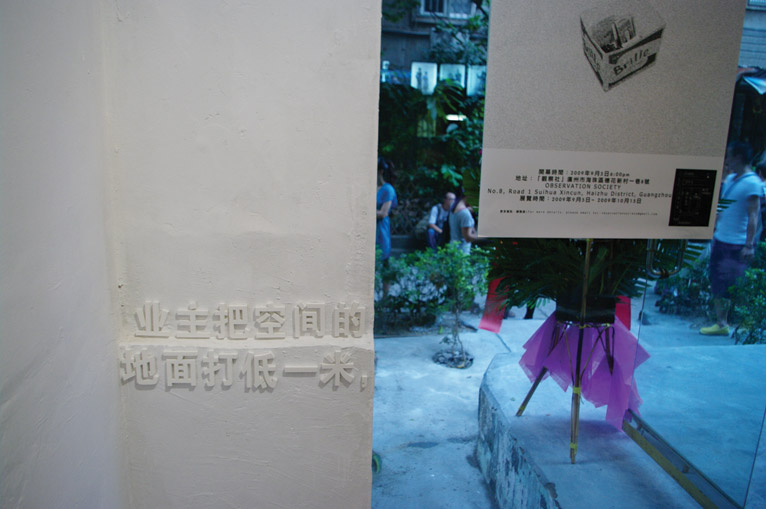

In 2008, artists Hu Xiangqian (then based in Guangzhou) and Doris Wong Wai-yin (based in Hong Kong) decided to open a non-profit space on a shoestring budget. The two shared a commitment to experimental practice and a frustration with the options for showing their work. Instead of bending their ideals to accommodate the requirements of existing spaces, the two artists decided to found a space of their own. They recruited Anthony Yung, a researcher at Asia Art Archive, and Lin Jingxin, an artist based in Guangzhou, to form what is now known as Observation Society.

Similar to the physical location of Arrow Factory, Observation Society is a small storefront space in an otherwise residential area. Tucked away off the main road and located a few steps above ground level, the former hair salon was chosen primarily for economic reasons. The space has been financed entirely by its members, and its audience of interest is primarily those involved with contemporary art. The local residents, on the other hand, seem uninterested in, even baffled by, the useless objects and videos on view in a space that generates no revenue.

The decision to set something up in Guangzhou may seem curious, but Yung explains it as follows: first, there are very few contemporary art spaces in Guangzhou, or perhaps only two—Vitamin Creative Space and Libreria Borges. Second, with an eye to trans-PRC collaborations, it is easier for Hong Kong artists to travel to Guangzhou than vice versa. Third, the cost of sustaining a space is much cheaper here than in Hong Kong, Beijing, or Shanghai.

Daily operations at Observation Society are entirely self-sufficient. Once, I curiously asked Yung to explain the buzzword, “alternative” and his interpretation of it projected onto Observation Society. He jokingly replied, “we are a group of poor people who are dumb enough to want to sustain a space like this… the key word to describe the artworks we exhibit is ‘unsophisticated.’”

The dumbness that Anthony Yung referred to translates to a set of shared values that transcend the dollar sign. Considering the group could also establish an art space in Hong Kong, where it would enjoy the possibility of benefiting from government funding and other philanthropic donations, the decision to operate in the Mainland seems bold. And yet paradoxically, being part of the Hong Kong funding system might jeopardize the artistic freedom they cherish, while in Guangzhou they go totally unnoticed.

Each artist who exhibits at Observation Society remakes the space in accordance with his or her practice. In this respect, Li Jinghu’s solo exhibition, Forest, was especially compelling. Li is perhaps the only contemporary artist currently living in Dongguan, an industrial city in Guangdong Province, where the main economy depends on processing electronic parts and industrial material. The artist used the space as his studio, assembling the recycled industrial waste he had purchased into a natural landscape. At the end of the show, the materials were resold to industrial recyclers, completing the industrial metamorphosis.

TEXT: Fiona He / TRANSLATION: Du Keke

THE DONKEY INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORARY ART (DICA)

Bringing the art context directly to a moving public.

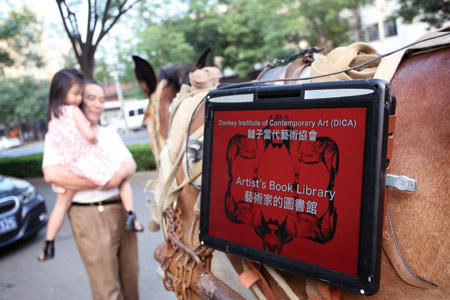

In Beijing, as in many Chinese cities, the far fringes of the metropolis offer strange possibilities for art. They are also the zones in which one is most likely to find donkeys. The Donkey Institute of Contemporary Art (DICA) is an initiative dedicated to supporting experimental contemporary art on the back of a donkey. Established in the Beijing summer of 2009, it is premised on the spirit of “steadfast oblivion” manifested by these beasts of burden. Founders Michael Yuen and Yam Lau, in their opening manifesto before DICA’s first show at 798, noted that donkeys “counter all forms of calculated intelligence, promotion and profit-making within the market place of contemporary art. They do so with the slowest possible speed, the most idle tactics and wandering work ethics.”

Michael Yuen notes, “DICA began with Yam and I talking about our practices, what we’ve done outside, and specifically outside of the gallery system. I’d seen a donkey across the road from the 798 Art District in Beijing and we thought this could be interesting. We were taken by the vague and overlapping point where the rural stops and the city begins. A symptom of this in Beijing is that donkeys and their farmers are coming and going around town, migrant workers are continuously arriving and leaving, taxi drivers are living on the city’s edge and driving into the city—the donkey was a very visible part of that.”

A seemingly cheeky intervention, in which video monitors are strapped to the back of a donkey, and other works are shown on a cart hitched to it, DICA grows out of an earnest concern about how art works in cities, be that inside or outside its devoted institutions. “I’m interested in the city in general and I’ve never really been interested in showing work in galleries,” says Yuen. “So this outside, mobile space, outside of the gallery, outside of those walls can be used as a platform. It also means that you’re much more connected to life. In the places where DICA has been located or has situated itself, it works best where there’s traffic flow, foot traffic. So the audience actually renews itself. You have people interacting with the work, who don’t particularly come with preconceptions or their preconceptions are much more varied than the ones of those going to see works in museums or gallery spaces.”

Despite its subversive claim to being “dedicated to supporting experimental art on the back of a donkey,” DICA is not actually about institutional critique. “It’s not an ‘anti-gallery’ thing,” says Yuen. “It has this opposition to galleries and the commercial world but it’s not denouncing them, it’s just another way of doing things. We’re outside of the standard structure here and therefore it gives us a chance to think about DICA, to think about the structure itself and where the structure could break down.” In fact, DICA has been increasingly collaborative with galleries, particularly Vitamin Creative Space. As it matures, this quirky artist-run space hopes to provide newer and better opportunities for art to fade into the urban fabric.

TEXT: Edward Sanderson / TRANSLATION: Du Keke

TAIPEI CONTEMPORARY ARTS CENTER

Since Taipei didn’t have a similar organization, they made their own.

Taipei Contemporary Arts Center is a non-profit organization. It’s sort of like a union: people obtain membership through a standard application process in which they agree to make financial donations, and, on this model, operations are carried out. The notion of it being a “center” originates in Yang Jun and his proposal for the 2008 Taipei Biennial, One Contemporary Arts Center, Taipei. His idea was modeled on European cultural organizations: a city needs large museums, small alternative spaces, as well as mid-sized art centers, like Berlin’s “temporary Kunsthalle”, that have virtually no collection of their own, and instead focus on research, exchange, experimental events, and so on. As Taipei didn’t have a place like that, Yang Jun “made” one.

When this “issue” was identified in 2009, curator Manray Hsu had just returned to Taiwan. Hsu had begun to discuss founding a space/association with curators Michael Lin, Meiya Cheng and Amy Huei-Hua Cheng, artists Chen Chieh-Jen and Tsui Goang-Yu, and academics such as Chen Tai-Sung, etc. They held a press conference, inviting media, entrepreneurs and cultural officials for a round table discussion of the issue. The entrepreneurial response was immediate: the JUT Foundation for Arts and Architecture would provide them with a 600-square-meter building in the old Hsimenting district, free of charge for two years, no strings attached.

Thereafter came the discussion of funding. Funding with no requirements seemed rather improbable, especially considering how strongly critical and socially intrusive TCAC’s events and exhibitions tended to be. Several warm-hearted local art

ists like Chen Chieh-Jen and Michael Lin donated works, and the first exhibition acted as a fundraiser. Sales proceeds were just enough to cover initial operations, and some buyers were designated as friends of TCAC, or officially referred to as “Lovers.”

Exhibitions always cost money. For September 2010’s Forum Biennial of Taiwanese Contemporary Art, for example, a loan had to be taken out. At TCAC, organizing an exhibition is not meant to be a service to the people. Curator, TCAC founder and board member Meiya Cheng says, “Abstractly speaking, Taipei does not have a space that allows exchange within the [arts] circle, or that holds experimental events. What we do is a response to the overall circumstances of Taipei’s art scene at present.” The layout of TCAC is both inexpensive and subversive. The office is on the first floor and uses cheap and ordinary aluminum windows for doors, to the effect that people outside can see in. The idea is that this transparency will serve to turn the strategic opacity of museums and cultural organizations on its head.

Even today, TCAC is neither entirely stable nor certain of its future. But as association members include past Taipei Biennial curators, the most active artists, city cultural officials, and academics, TCAC receives constant attention. “Here, artists do things more efficiently. They don’t have to deal with the wastefulness of the civil service system. When we critique the current political and commercial complex, we must maintain our independence and freedom. Under this principle, we even welcome help from those struggling against the government, and from entrepreneurs.”

TEXT: Aimee Lin / TRANSLATION: Michael Einar Engstrom