YANCAI IN CHINA

| December 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 6

The Chinese name for the material consists of the characters for “cliff” and “color.” The Japanese call this material iwae and the Taiwanese call it jiaocai. By any name, its is a compelling story of an ancient skill, its transmission out of and back to China, and its somewhat awkward attempt to find a place in art today.

“Eastern Hues and Chinese Images—the Study of Chinese Yancai Painting” opened on September 9 at the Art Museum of the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. The exhibit depicts the origins, characteristics and current state of yancai painting. Although the form has ancient roots in China, its current incarnation emerged only in the mid-1990s. A number of painters returning from study in Japan began to use traditional mineral pigment methods, and they referred to the works they produced as yancai paintings. These painters had studied Japanese painting, which centuries ago absorbed a great deal of influence from the Dunhuang Buddhist cave murals. Today, this controversial painting method is the subject of a major at art schools around China.

COPYING FROM DUNHUANG

The Dunhuang murals provide a broad, traceable background for yancai painting. Dunhuang’s Mogao Buddhist grottoes were discovered in 1900. Beginning in 1937, artists including Li Dinglong, Zhang Daqian and Chang Shuhong began visiting Dunhuang to copy and study the cave paintings and organize exhibitions. In 1941, Yu Youren, then President of the Control Yuan in the Nationalist government, visited the Mogao caves during an inspection of the Hexi region. Yu’s visit moved him to call for the formation of a “Northwest Cultural Relics Field-Study Group” to conduct research at Dunhuang.

The Dunhuang Art Institute was officially established on New Year’s Day in 1944. Chang Shuhong was named its first director. In the decades since, the institute has undertaken research, archeological study, documentation, and protection of the grottoes.

Today, Dunhuang Academy—the present incarnation of the original institute—sits beside the Mogao caves. Copying is among the focal points of the work conducted at the academy. Copies of the cave murals are divided into three categories: restorative copies, extant copies, and archival copies. Restorative copying is complicated: the copier must attempt to recreate the appearance of the original, complete painting. This time-consuming process draws on laboratory analysis, and thus far, not one cave at Mogao has been completely restored. Extant copying entails the documentation of the present condition of the cave murals, including the effects of damage and oxidation. Today, the largest proportion of copying is archival copying, in which artists draw on their experience to contrast the characteristics of paintings from the same period, restoring some damaged elements in the copying process. Archival copies include the restored caves at the exhibition center, where the colors have been brightened and the lines are more complete. When copying work at the caves first began, artists mostly used gouache paints. These paints proved insufficiently stable: over time, the paintings became discolored. Later some artists began using mineral pigments instead of gouache, allowing a more accurate reproduction of the texture of the murals at the time of their creation. However, Dunhuang Academy did not complete the switch to mineral pigments until 2000. According to Hou Liming, the director of the Fine Arts Institute of Dunhuang Academy, there were a lot of mistakes in the first copies, but these copies by respected senior artists possessed a valuable “consistent tone.” In contrast, today’s students, lacking a foundation in classical studies, fail to achieve the same quality. For this reason, the young students dispatched to the institute each year must first spend one year as a guide in the reception area in order to become immersed in the cave lore.

The murals in the caves were all drawn with mineral pigments and small quantities of botanical pigments. These mineral pigments were the first painting medium commonly used in both the West and the East; later, in the West, oil paints replaced mineral pigments. The tradition of mineral-based paints continued in Buddhist paintings in China, but more broadly, colorful paint fell from popularity and black-and white ink became the predominant medium. This trend is also reflected in the historical progression displayed in Dunhuang’s Buddhist paintings.

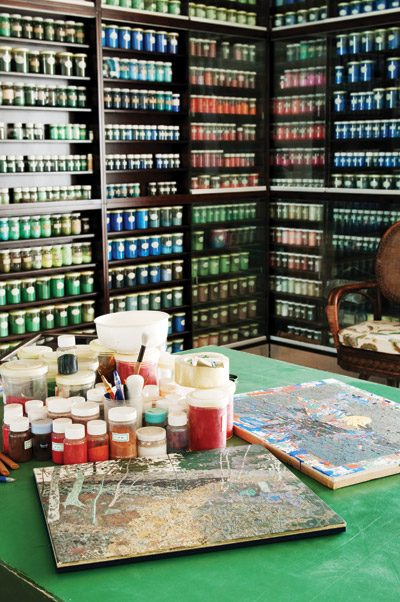

Color is also the most direct and important continuous link between yancai painting and the Dunhuang murals. Shelves holding little bottles of different colors of paint cover an entire wall of the institute, suggesting a complicated multitude of colors. “Colors and grades are two separate matters,” Hou Liming said. Ultramarine, for example, had five grades in antiquity: ultramarine-1, ultramarine-2, ultramarine-3, ultramarine-4, and white-ultramarine. The Japanese later developed thirteen grades of the same color. The difference between the grades lies in the coarseness of the grains of pigment; coarser grains yield a heavier hue closer to the original color of the mineral, whereas finer grains produce a lighter color. Thus, the same mineral is manifested in different colors of paint. “The colors of the Dunhuang murals are in fact very simple. There are two cool colors, ultramarine and malachite, and then also ocher, cinnabar, vermillion, black and white—basically just these. Then there’s a little gold, and by the Tang Dynasty, some shades of gray. It looks more complicated today because of the gradual change in the colors over the course of history. Some have faded, which causes the colors in the paintings to seem much more diverse.”

The mineral pigments originally used in the cave murals were relatively bright, but at present, the artists at the institute use some grayer shades to represent the present appearance of the timeworn paintings. The origins of these colors are mostly domestic: in the mid to late 1990s, Wang Xiongfei, having studied pigments in Japan, produced several shades of gray. These colors were also originally used in Japanese yancai paintings—the Japanese tradition is yet one more link between yancai painting and the walls of Dunhuang.

VOYAGE TO JAPAN

Zhujiang New Town does not seem all that well connected to the city of Guangzhou. This is where artist Chen Wenguang lives and works. From the windows upstairs, a swath of green is visible: the South China Botanical Garden, Chen’s original reason for choosing this location. It’s quiet and peaceful: good for the creative soul. One of the leading living practitioners of yancai painting, Chen also teaches on the subject at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts.

Two works recently removed from the exhibition lie in Chen’s studio: one painting of a lotus leaf, and one of an ornate hair ornament resting on a woman’s head. Chen works extremely slowly, often spending months on a painting. The craft of yancai painting is complex, and much more time-consuming than gouache or oil painting. Mineral-based pigments cannot be blended like gouache paints or watercolors can. They can only be “balanced.” If Chen needs purple, he paints on a red base, and then, once the paint has dried, he adds blue layers. The gelatin and special hemp paper he uses both come from Japan. He uses cloth or paper to blot the paint after applying it, creating a mottled effect. And as for the arrangement of colors—the processes of daubing, scraping, brushing, overlapping, and colliding—these are all components of the pursuit of delight and “beauty” in its classical sense.

The lotus leaf painting originated in Chen’s memories of Tokyo: an impression left by a scenic area of Ueno at dusk. Ueno is home to Tokyo University of the Arts, where a number of Chinese students showed up in the late 1980s to study Japanese painting. Many of the people presently teaching and producing yancai painting in China come from this group of students. Several art schools in Japan now teach yancai painting, but at the time, many of Japan’s most famous painters were teaching at Tokyo University of the Arts, providing an unparalleled pedigree.

Chen Wenguang had previously studied ink painting at Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. In the late 1980s, a few exhibitions of Japanese paintings appeared in Guangzhou. These paintings captivated Chen, and he paid his own way to Japan to study under Kayama Matazo. Kayama, descended from an artisan family of clothmakers, was an expert in clothdyeing techniques. He had also extensively studied gold and silver leaf techniques, forming a unique personal style. His paintings had a strongly decorative element, reflections of which are visible in Chen’s work. Two impetuses underlie the Japanese propensity for this decorative style: first, the extension of kimono leafwork to painting; and second, in addition to mineral pigments, the Japanese had used ground stained glass to make paint. Unlike mineral pigments, glass-based paints are quite stable; they do not vary in color based on the coarseness of the grind. After learning mineral pigment painting techniques in ancient China, Japanese artists developed their own styles. A continuous lineage connects ancient China to late twentieth-century Japanese masters such as Kayama, Higashiyama Kaii, Hirayama Ikuo and Takasugi Tatsuo, who continued to apply this traditional artistic craft to reflections of contemporary life.

Hou Liming also studied in Japan, but his story presents a different path. Having previously studied oil painting, Hou spent three or four years at Dunhuang Academy, and then, in 1989, traveled to Japan on a government sponsorship to study under Hirayama Ikuo at Tokyo University of the Arts. Hirayama survived the atomic bomb in Hiroshima in 1945. A devout Buddhist, he had visited many of the religion’s sacred places around the world. He was fascinated by Dunhuang, and, like many Japanese who lived through the war, Hirayama had powerful feelings toward China. Hou’s opportunity to study in Japan was, in fact, Hirayama’s idea. Previously, many Chinese art students had come to Japan to study preservation techniques, and Hirayama wanted to cultivate Chinese talent to conduct the work of copying the Dunhuang murals. His studio was unique at the university in offering training in copying. “Compared to creating, copying requires a stronger understanding of materials. Basically it was training in techniques. The curriculum was not complicated. If you can get one painting right, then you’re set,” said Hou.

Hou Liming recalls that mineral materials were completely unfamiliar to him when he first arrived in Tokyo. The elderly gentlemen at Dunhuang Academy were making good copies, getting the spirit of the murals right, but the paper versions did not have the feel of the originals on the walls. Japanese copying methods heavily emphasized texture, to the point that many referred to the process as reproduction instead of copying. All the information in the original, including texture, had to be included in the reproduction. “We use brushes for the undertone. Once the brushing process is complete, they have to ‘dot’ in various colors. It takes a tremendous amount of work. Ordinarily, it takes a year to copy one painting.”

The rules for copying are strict, in contrast to creative painting, for which there are essentially no rules at all. Hou Liming, Chen Wenguang and their peers received strong technical training in Japan, but their later creative development relied on individual inspiration. Hou said his own work continues to reflect the influence of his teachers. Hirayama’s own paintings are quiet, imbued with history and poetry. Hou’s recent work draws on Dunhuang, creating scenes akin to Hirayama’s, but his paintings remain representative of only a single mode, a limitation that relegates him to his mentor’s shadow.

RETURN TO CHINA

At the art museum in Guangzhou, preparations for “Eastern Hues and Chinese Images—the Study of Chinese Yancai Painting” took six months. With the task of organizing the concept of yancai painting, members of the yancai world (if such a “world” can be said to exist) undertook a process of inward evaluation and outward explanation. The term “yancai painting” originated in the mid-1990s, winning out over diecai. The yancai moniker is more appropriate, in that yan—which means rock—highlights the essential feature of this method of painting: the use of mineral colors.

Different approaches to the application of this technique have appeared in recent years. Artists such as Chen Wenguang and Hou Liming emphasize “resolving issues within a scene,” adhering to the traditions of yancai. Hou finds yancai to be an appropriate medium for subjects inspired by the influence of the Mogao cave murals and the features of his natural surroundings in Dunhuang, just as ink painting enjoys a special representative relationship with the Jiangnan region, south of the Yangtze river. “My own work draws on the blue and green landscapes of the Song Dynasty, expressing a kind of artistic conception.” Dunhuang is a quiet place in which the presence of cultural history is strong, contributing to a classical artistic sensibility. Chen, in the southern metropolis of Guangzhou, has begun to use the expressive power of the medium to portray his reflections on fashion and contemporary society. In a painting titled Is There Anything That Becomes Passé More Easily Than Fashion? the finely detailed woman’s hair ornament, both extravagant and fragile, seems to fill the canvas. But at the Guangzhou Academy, Chen’s teaching methods emulate his educational experience in Japan. Technique comes first, and the development of creativity is a matter of each student’s individual talent and intelligence.

Hu Wei’s studio at the Central Academy of Fine Arts was established in 1997. In 1996, he received his doctorate from Tokyo University of the Arts. The art of Hu and his students is closer to installation, and mineral pigments are just one among many media they use. When Chen Wenguang first returned to China, Hu invited him to teach at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, but Chen said he sensed some resistance to yancai painting in the Beijing art world. Yancai was thought of a Japanese technique rather than a Chinese one, and also, the domestic painting world seemed unfamiliar with yancai and unwilling to accept its legitimacy. The academy wanted to recruit outsiders to bring yancai into the contemporary, mainstream art scene, but doubts remained over whether this effort constituted the advancement or the corruption of yancai. Yang Jingsong, another artist in the Guangzhou exhibit, never studied yancai, but he uses mineral pigments to form contrasts in his work.

“Yancai is not merely decoration. Its expressive power is actually very rich. It’s about using color to paint.” Hou Liming’s words also highlight another facet of the ambivalent reputation of yancai painting. Due its strong craft aspect, yancai is often seen as primarily decorative. Compared to acknowledged media, such as oils, it remains to be seen whether yancai will find acceptance and attention—and a market—in the world of contemporary art.

In July, “Golden Sky,” Yu Hong’s show at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, provided another example of the interaction between the present and the ancient art of the Dunhuang murals—but not in terms of medium. When she was a teenager, Yu saw her mother’s copies of cliff murals from Dunhuang, and she was fascinated. “They seemed to transcend boundaries of time and space,” she said. She once visited Dunhuang during her university years, but she never studied the cave murals in depth. She also became acquainted with the “Dunhuang class” while studying at the Affiliated High School of the Central Academy. In 2008, when Wang Xiaoshuai was filming his documentary about Yu Hong, After All These Days, she once again visited Dunhuang, carefully studying the caves. She said she was most attracted to the overall atmosphere. Previously, in various exhibitions, she had only seen isolated aspects of the cave murals, but at Dunhuang, she was able to enjoy the complete effect: the enchanting, sacred ambiance formed by craftsmen and artists over hundreds of years.

Yu Hong never studied yancai techniques, and oils remain her principle medium, but she found compositional inspiration in the Dunhuang murals. “Questions for Heaven” draws on the composition of Mogao cave #321’s “Meeting with Buddhas and Bodhisattvas,” inserting images of modern people. Buddhist paintings, which tend to be strongly narrative, have developed visual structures well suited for narrative portrayal. Yu Hong is interested in radial compositions, in contrast to the conventional four-sided framework of painting; breaking down this framework and giving her work a kind of explosiveness has long been one of her preoccupations. Many of the early Dunhuang murals have radial compositions, especially those from the Northern Liang and Northern Wei periods. The convoluted feel of these murals seems quite appropriate for representing the upheavals and internal transformations of contemporary life. And painting on a ceiling allowed Yu to experiment with a “mid-air” effect. She is no expert on traditional mineral pigments and yancai painting; she knows only that these materials have a lot of limitations and require a high level of craftsmanship.

“But greater limitations also offer greater opportunities to fill space—this relies on the artist’s own approach. Painting itself has become marginalized in the broader contemporary art world, but that certainly doesn’t mean painting is becoming stagnant or extinct,” Yu Hong said.