TRANSCENDING TIME: LUO DAN’S “SIMPLE SONGS”

| June 7, 2011 | Post In LEAP 8

THE FIRST TIME I encountered Luo Dan’s “Simple Songs” was in the small city of Lianzhou, in Guangdong’s mountainous north. He had just finished taking this group of photos, first driving from western Yunnan’s Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture back to Chengdu, then flying on to Guangzhou, then traveling by bus to Lianzhou, to serve as a juror for the 2010 Lianzhou International Photo Festival. Throughout this long journey, Luo carried a small silver box, inside of which were delicate glass plates separated by thick layers of sponge. Back in his hotel room, he donned white gloves. As he pulled each of the plates from its plastic bag, the room went breathless. This was the first time I had ever beheld images made with the legendary wet plate collodion process.

SILVER ON GLASS

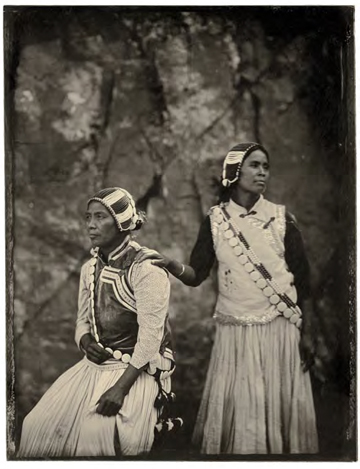

The six by eight inch glass panels are arranged on a black microfiber cloth, set atop a bed. These are plein air portraits of Lisu (a Chinese minority nationality) Christians in Yunnan. A close look at their silhouettes, facial expressions, clothing, and environment reveals that every “pixel” is actually formed of radiant, minutely grained silver. In the dusky light of a standard hotel room, the silver flecks flicker, precious metal at sunset. A few of the figures appear vague— the plates exposed too long or the focus not quite right— but this somehow only adds to their soulful quality. I can’t but think of descriptions from early in the history of photography of the camera as a vehicle to capture the soul, and the discursive remains of magic and witchcraft that still litter the vocabulary of the medium today.

The classical composition and calm facial expressions imbue these images with a sense of having come from a century ago. We know that Luo Dan is deeply taken with the portrait photography of the nineteenth century. The most significant impact of the birth of photography on mass society was nothing other than offering humanity its first chance, outside of the precious sphere of painting, to leave an impression. People became suddenly conscious that a person, nearly any person, could leave their “image” to posterity. Under the influence of traditional portrait painting, portrait photography assumed an incomparable importance in the public mind. A portrait was something left to children and grandchildren, something that existed with the explicit mandate to transcend time. This is what Luo seeks to restore: through refined photographic technique, he creates images with the power to defy temporality.

Wet plate collodion is a classical photographic process, long ago eliminated from practical use. In modern times, only the most devoted of enthusiasts or researchers have even looked back at this technique. Artists using this process to create works of contemporary art are a rarity. Having enjoyed twenty or thirty years of popularity in the mid-nineteenth century, it was quickly replaced by the dry plate techniques to which it gave rise, which in turn evolved, over several more transitions, into film. From its birth, the real value of the wet plate print lay in the model of printing from a negative that it pioneered, filling in the key shortcoming of the Daguerrotype, its irreproducibility. (To use today’s language, it transformed the photographic object from the printed picture to the printable image.) This advance at once clarified the development process, simplified operations, and lowered costs. Glass plates, of course, are cheaper than silver ones. The “positive-negative model” thus introduced is the fountainhead of film photography.

For Luo Dan and others today using this technology, the import of wet plate collodion printing lies in its technical complexity relative to modern film. The most difficult part of the process is that the light-sensitive film must be prepared on the glass plate on-site, which means that the photographer must carry around chemicals such as alcohol and ether (used in producing the base layer), silver nitrate and acetic acid (used to make that layer light sensitive), and ferrous sulfate (used for image fixation). Many of these dangerous substances have been outlawed for personal use. Another trouble is that once the collodion has been prepared and treated with the light-sensitive chemicals, it must be used while still wet, and then directly delivered to the dark room for development and fixation. This means that the dark room must be very close by. The third difficulty arises because the light sensitivity of collodion plates is quite low, so that even when shooting outdoors in daylight, exposure times can last from a few seconds to nearly a minute. For the subject, this means maintaining stillness throughout.

This long process of preparation and waiting leads to a ritualistic sensation for the subject, bordering on a Zen-like state. Taken together, these practices have the effect of pulling the subject out of his or her specific life and material circumstances. In other words, this obsolete photographic technique is transformed by Luo Dan into a kind of spiritual image conjuring. Set against a broader backdrop of ascendant film-based, and now digital, photography, the commitment by a small number of artists to these classical methods marks a return to the very essence of the photographic image. Luo himself says, “As photography grew ever more technologically complete, it drifted ever farther from its earliest starting point. External factors entered in, and its purity was gradually lost.”

FROM SWEEPING GLANCE TO CAREFUL STARE

Luo Dan does not believe that the strength of photography lies in its capacity to express specific content. Images fixed over a relatively long time, rather, are able in turn to transcend time itself. This special capacity he sees as both the historical root and future of photography. By choosing to work in wet plate, he has committed not only to a superficial technique, but to a set of values, which he sees as prior to those of industrial civilization, belonging to a simpler condition. Metaphysically speaking, he seeks out the value of transcending time.

Since his 2006 series “National Highway 318,” Luo Dan’s photography has displayed a knack for bypassing traditional conventions. We must mention here that Luo, a graduate of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, worked for eight years as a news photographer with a focus on entertainment, adding daily to the swelling sea of images for a consumer society. In 2006, Luo resigned his post at his newspaper and drove a Jeep from Shanghai to Lhasa (along Highway 318), using a medium-format film camera to capture what he saw along the road. (As a reporter, he had used a digital camera.) In 2008, he set off again, shooting the series “On the Road, There: The North and the South of China, 2008.” It would be easy to characterize Luo’s work before 2010 as “road photography.” Only when he began “Simple Songs” did he stop moving, living with his subjects for half a year and producing only a few dozen images. His earlier series produced thousands.

The Lisu village which Luo Dan photographed in this series lies on the cultural and geographic periphery. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Western missionaries spread Catholicism and Protestantism through the region, along with modern irrigation, medicine, and other technologies. They codified a Lisu-language orthography based on the Roman alphabet. Nujiang remains even today a Christian community, with over 70% of its population believers. It is a complete religious society, hidden high in the poor, remote mountains. Luo began by participating in their gatherings, going on to live with them. Each photograph took nearly an hour to make from preparation through development. The ethnic garb his subjects wear is their Sunday best. Most of the photos were taken after mass.

The state of constant travel evident in “National Highway 318” and “North and South” is the decisive condition of their production and realization. In “Simple Songs,” on the other hand, we see a deeper side of Luo Dan, where he sets aside the harsh reality of being on the road and returns to roots. The images he makes are deeply dependent on his method, which is to say both his specific photographic tactics and his general mental state. In both instances, the photographic results are inseparable from the process that begat them, bet that a journey of several thousand kilometers or the long minute of a camera exposure.

In both appearance and disposition, the Lisu Christians of Yunnan express values dear to Luo Dan, his notion of the ideal existence of man in the world. “National Highway 318” is instead a critique, a search for the coldness and absurdity of reality on the road, penetrated by a deep loneliness and anger. The absurdity of reality made for strong visual stimuli in every composition; in “North and South,” Luo’s anger is sublimated into cold remove, his glare replaced by a cool glance. By “Simple Songs,” this glance is further transmuted into a classical, yearning stare. In images that read like historical elegies, empathy replaces judgment and observation. Harmony triumphs.

Why did this change occur? Clearly it was an outgrowth of Luo Dan’s own spiritual maturation. In his words, “I traveled a long road, saw a lot of things, and in the end realized that all differences are actually similarities. And so I stopped, and looked in a single place for something unchanging, tried to figure out why this place had the power to stand still in time.”

Here is an artist enticed by the spirit, unwilling to speak of his work in terms of what it is “about.” Instead, he sees each period in his own work as a distinct phase in his life, a separate period in an ongoing journey. Thus while his images express values and abstract concepts, they are grounded on the notion of photography in the most basic sense.

Luo Dan’s “Simple Songs” are neither “feature photography,” nor “anthropological photography,” nor do they have anything to do with the recently named practice of “private photography” (si sheying) that looks to document an interior world. And yet looking at “Simple Songs” against the background of these classifications actually helps us to appreciate their specificity even more deeply, to become happily aware of another set of possibilities for the medium. Thinking back on the moment, imprinted forever on my mind, of seeing those glass plates, I ask myself: Could those silver particles shining like moonlight, refined through the physical and mental form of the images they convey, have been emitting anything other than what Benjamin called “aura?”