ART EQUITY TRADING: A NEW PONZI SCHEME

| December 8, 2011 | Post In LEAP 11

The founding aspiration of the local and regional “Cultural Assets and Equity Exchanges” now popping up around China was to create an adjoined service platform between culture and capital: providing cultural industries with a wider range of access to funding and implementing a system of convenient, standardized, and efficient service and support for investors. Set apart from traditional art market transactions, this model was meant to attract greater involvement on the part of collectors and investors. But from 2009 to 2011, the operations of cultural equity exchanges nationwide may have yielded results counter to their desired effect.

JUNE, SEPTEMBER, AND November of 2009 marked the successive establishment of the Shanghai, Tianjin, and Shenzhen cultural equity exchanges. Zhengzhou, Chengdu, Guangzhou, and Guangzhou followed close behind in 2010. According to incomplete statistics, there are at present in China more than 20 such exchanges— whether already established or otherwise preparing to launch— and this number is constantly growing.

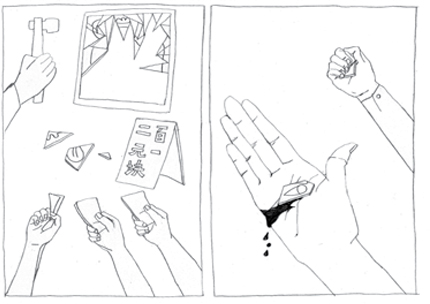

The current model shared by all domestic cultural equity exchanges is based on the “splitting” of packaged art assets. So-called “equity splits” entail dividing up proprietary rights along with whatever revenue is produced on that basis. By subscribing for shares in splits, investors can obtain ownership rights over material components of investments and related equities, enjoying both immediate and long-term benefits. Investors can apply for the purchase of shares resulting from the splits, and in turn can obtain a corresponding ratio of ownership rights over the item in question. By the hand of the equity exchange platform and what it holds during a given period, investors can enjoy the fruits of appreciating returns.

The process of listing an asset package on the market is as follows: first, an artwork’s distribution agent will package one work or a combination of several works and apply to the relevant cultural equity exchange platform; next, a third-party evaluation agency will assess the authenticity of the package. The transaction will then be verified by the equity exchange’s listing committee, after which an insurance company will underwrite the artwork or works. The distributing agent is then responsible for a pre-offering roadshow of the works. Finally, the package can be listed and its shares sold.

In July 2010 the first split equity art package was officially listed on the Shenzhen Culture Assets and Equity Exchange. The package— 12 works by painter Yang Peijiang— went on the market at RMB 2 million, with listing subscriptions split into 1,000 shares at RMB 2,000 each. In December 2010, artist Huang Gang’s “Red Star and Box” series was listed on the Shanghai Cultural Equity Exchange, and in January 2011 the Tianjin Cultural Artwork Exchange launched Bai Gengyan’s Roaring Yellow River and The Autumn of Yansai Lake. In May 2011 the Chengdu Culture Exchange listed a package of 23 works by contemporary artist Zhong Biao. These four equity exchanges all operate on distinctly different models. The Tianjin exchange is geared towards the general public: a low threshold for investment and the “T+0” standard of asset class securitization allow shares to be sold the same day they are purchased. Meanwhile, the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges have fewer splits during asset sales: they do not apply the “T+0” standard, and shares are only available to a specific clientele— making the threshold for participating investors comparatively higher.

The Tianjin exchange model of asset class securitization has been most subject to criticism. In January 2011, two separate institutions assessed Bai Gengyan’s Roaring Yellow River and The Autumn of Yansai Lake at respective valuations of RMB 5 and 6 million. In accordance with the Tianjin model, each work was thus split respectively into RMB 6 million and 5 million shares at RMB 1 per share. The capital threshold for investors was a mere RMB 50,000, with a minimum purchase of 1,000 shares. Statistics show that for both paintings together, the capital generated from share purchases totaled more than RMB 20 million, with a success rate of 40%. Their first day on the market, the two works rose in value more than 100%, and in only two months the trading price of each soared to RMB 17 per share, resulting in a net rate return 17 times larger than the initial valuation. Calculated on the basis of each share standing at RMB 17, the market value of Roaring Yellow River had already broken the RMB 1 billion mark; whereas Bai Gengyan’s highest priced work in the open auction market One Thousand Peaks Meet the Clouds (2005) sold at a hammer price of RMB 3.92 million. However, only four of Bai’s works thus far have been valued above RMB 1 million; many industry experts find it ludicrous that Bai’s works, having been devided into shares, should exceed RMB 1 million in market value. In March, in order to prevent the further explosive rise and fall of prices, the Tianjin exchange began incessantly adjusting and revising protocols— thereby attracting media attention and dissatisfaction on the part of investors. As of September 2, Roaring Yellow River was priced at RMB 3.05 per share and The Autumn of Yansai Lake at RMB 3.04 per share; participating investors have suffered great losses as a result. In March 2011, the Tianjin exchange was forced to suspend all trading activity. On July 29, 2011, after three months of business adjustment, the Tianjin exchange launched its third installment of market-listed works: a package of contemporary oil painter Yang Feiyun’s works Festival of Life and Lily along with a package of jadeite beads. On July 30, the two packages dropped to values below their issuing prices. This kind of incident adequately reflects the cautious attitude of investors with regard to the splits model. In March 2011 the Shenzhen exchange also halted operations, not to resume again until August 22.

THE DEBATE OVER CULTURAL EQUITY EXCHANGES

SEVERAL YEARS AGO, before the opening of the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges, Chairman of Beijing Huachen Auctions Gan Xuejun participated in a seminar on the feasibility of “works of art as subjects of title transactions.” While many participants expressed doubt, Gan supported the art exchanges. Gan reasoned that with a relatively low investment threshold, the average buyer could elect to “own” a piece of art through buying into its “shares”— a phenomenon markedly different from the traditional auction model, where “what you get is what you can afford.” The emergence of the art exchange draws more public attention to the industry than ever before; it follows that as the art industry “pie” grows increasingly large, so does the size of each participating member’s piece. Gan has also stated, however, that the art exchanges still have many technical and practical issues that remain to be solved— among them the lack of a system for the authoritative assessment for pricing or a department specializing in the monitoring of these markets. Dong Guoqiang of Beijing Council International Auctions feels that the exchanges will not incur losses on the part of auction collectors, but will rather play a large role in building the industry’s popular base.

Presently each art exchange has different means of obtaining artworks for asset packages. Some exchanges may acquire works with the consent or participation of the artist himself; some obtain consent from the artist’s family; and some procure works from cooperating galleries. Thus different exchanges have different relationships to galleries. For the Shenzhen exchange, gallery participation is very important. Galleries are directly responsible for providing dealers with packages of outstanding works as well as ensuring the market stability of these works through continued management and liaising with artists. The first asset package listed on the Shenzhen exchange is a good example. Zhang Hong, general manager of Hong Bao Zhai gallery— the gallery acting as agent for Yang Peijiang’s works— remarked, “The impact of the Shenzhen art exchange trading model on art galleries manifests itself in three ways. First is the effect of advertising: an open market for the exchange of art bolsters advocacy for artists and galleries alike, and attracts more public attention to artists—further bringing to light the value of their works. Second is the financial impact: the art exchange provides galleries with a financial platform, increasingly enabling them to solve problems of funding. Third, the exchange plays an important role in the standardization of art trading.”

The Chengdu Cultural Equity Exchange has released an asset package comprised of works by contemporary artist Zhong Biao. The Zhengzhou Cultural Art Exchange is currently preparing to release a package of works by contemporary artist Xu Weixin. For an artist, being listed on the market means expanding the scope of public awareness and disseminating works to a wider audience. Bai Gengyan’s case is the most obvious example; considered to be one of the great masters of Tianjin, Bai was not widely known beyond the area. But within a short period after his works were listed he experienced a rapid increase in public recognition. In an interview with Art Market magazine, Xu Weixin stated, “While artists should not pander blindly to the art market, artworks are being marketized all the same, and artists have to position themselves wisely. Of course the system should be in healthy condition; it should be regulated in a healthy way, and this applies to the market itself too. Public opinion should also be well-preserved and well-maintained. But on the whole, the financialization of art can be a good thing. As an artist, I personally am optimistic. I just hope the art market can develop in a healthy direction.” From the artist’s perspective, splitting up a work’s ownership rights is not the same as trading it away as in a gallery or auction house. In Xu’s mind, the split does not imply any loss for the artist.

But objectively speaking, when an artist permits the public listing of his works he is presented with a double-edged sword. On the art-trading platform, fluctuations in price and value are more transparent than ever. If a work is priced too high, or if due to the limitations of the current rules of an exchange its price endures volatile fluctuations, the future market performance of the work will be in danger. Do artists really mind taking this kind of risk?

ARE THE “SPLITS” THE TRUE CULPRIT?

EXCLUDING OTHER NEGATIVES— like a lack of systematic and authoritative evaluation criteria for asset packages— at the heart of these art exchanges is the concept of the “equity split.” And whether equity splits are instantly successful or the traditional gallery-and-auction model remains dominant, cashflow still comes primarily from the investment revenue stream: it is not endogenous to the works of art themselves. That is to say, if not for collectors and investors buying works at higher and higher prices, the works would not generate any cash flow. In reality, when it comes to works of art, equity splits and asset class securitization bring in income from investments only if investors bid up in droves. Only then is it possible for equity owners from previous intervals to see a real stream of revenue. It cannot be denied: some of these characteristics also happen to be the characteristics of a classic Ponzi scheme.

Ultimately, no one cares anymore who the artist is behind a market-listed work or how many shares there are to each single work of art making up a package. There is no one left asking what the price of each share is or whether or not this pricing is reasonable. Questions that ought to be at the very core of trading have all become negligible; as long as there is always a higher bidder to take over, the stunts and shenanigans of equity transactions can continue. Indeed, sellers can pocket a profit and get out, but the benefits they will enjoy all depend on the price the buyer puts up for partial equity. This is a process full of uncertainty: if a potential buyer’s bid is lower than the seller’s price, the transaction is a failure. The Tianjin exchange’s constant limit-down is a true reflection of this uncertainty.

In essence, the current splits are equal to a kind of virtual equity, as opposed to true proprietary ownership over works of art. It is impossible for investors to gain “holding” over a work by buying up the majority of split shares; true ownership in accordance with existing trading rules is almost entirely unrealizable. The reasonable next step in the development of the art exchange ought to be the transfer of physical ownership. Otherwise “equity splits” are just speculation— a glorified game of pass-the-parcel.

Up until now, there has not yet been one authority at the national level whose function is to monitor or regulate these trade platforms. A lack of effective supervision means a lack of protection for the rights and interests of investors. Indeed, the State Council is preparing to promulgate a policy regarding the rectification of past deviations and the standardization of further developments in the art equities market— no doubt a positive step toward protecting the rights and interests of future investors. But in the end, hopeful participating investors should be warned: in reality, purchasing proprietary rights over a work of art that has been split into this many pieces makes it nearly impossible to actually own that work of art, let alone enjoy the spiritual rewards that accompany collecting art. Rather, what we have here is nothing more than an investor’s game. It is not as pretty as it looks.