BEIER / RICHARDS / PROUVOST / SI-QIN

| March 8, 2012 | Post In LEAP 13

1. NINA BEIER

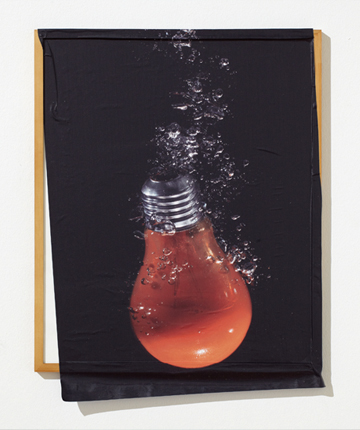

Take Danish artist Nina Beier’s sculpture series, “The Demonstrators”: posters of stock images, such as of a light bulb or rope, are dipped in glue and draped upon various found objects, which sometimes hang from the ceiling. The slick, color-blocked industrialism of the found objects, which include a tire suspended by a red chain acting as a trapeze and a common radiator, could falsely evoke the impression of a hastily conceptualized, un-monumental coolness; such an aesthetic has become endemic to Western MFA departments. What is convincing is Beier’s meticulous usage of found material— hanging upon the radiator is the image of not just a rope, but a rope that has finally frayed to its last connecting strand, about to succumb to its inevitable unraveling. On another radiator is an image of a rope freshly cut, its serpentine, carefully crisscrossed fibers now useless. A poster bearing an image of a potato is draped over an old conference table— a humbling domestic reminder in a context charged with power. In Portrait Mode, the artist arranges vibrant secondhand clothing in large frames, resembling Op Art paintings. As our attire is generally thought to serve as both a status symbol and a means for personal expression, the artist views these disused clothes as anonymous portraits; assembled together, these create an eerie composition.

Beier, born in 1975 in Copenhagen and based in Berlin, is represented by Laura Bartlett, London, and Croy Nielsen, Berlin. Beier has recently mounted shows at Kunstal Charlottenborg, Cophenhagen and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, and participated in the 2011 Public Art section of Art Basel Miami Beach, curated by Christine Y. Kim at the Bass Museum of Art.

2. JAMES RICHARDS

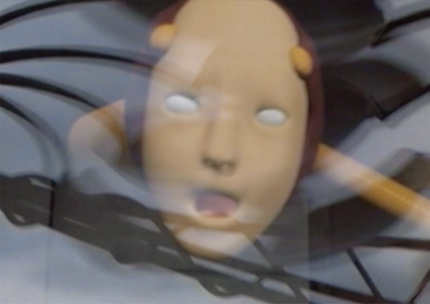

The work of Welsh video artist James Richards could best be described in the vernacular of painting. Richards, who obsessively replays and internalizes found footage, sequences montage-like compositions of emotive sound and video fragments— each constituent part of a loosely defined stroke in a larger composition. Abstract, scintillating clips bleed into moments of unfolding, ripening realism. Take, for example, the beginning of Richards’ Disambiguation (2011): In bird’s eye view, a remarkably normal-looking, petite young man lying on a bed nestles into a larger man, presumably his lover. The larger, equally unremarkable-looking man holds a video camera and documents their encounter in a ceiling mirror. Once the eye sorts out this strange but beautiful perspective, it becomes apparent that the smaller man is bound at the legs and leashed around the neck, a slave to his physically more impressive master. After the latter awkwardly remarks on what a nice shot it is that he is filming (replete with the intensity of a Hollywood sociopath), Richards cuts to a shot of two women in a dark room, singing and flirting upright on a bed under a diaphanous sheet. The intimately, poorly sung soundtrack carries into the next clip of a man, a self-professed voyeur photographing women in a lush, verdant forest. Following this are successive clips of a young man who jerks off with such frequency that the act appears more routine than arousing. Most unique to Richards is his ability to take an extremely subjective, personal approach to filmmaking without alienating his audience with cloying clichés, effectively approaching the most personal issues— such as coming to terms with the darker sides of one’s sexuality, drinking too much, and so on— in an impressively universal manner.

Richards mounted a solo presentation at Chisenhale, London in the autumn of 2011, and with Ed Atkins and Haroon Mirza, took over the screens and signboards of Times Square as part of a collaborative installation for the Zabludowicz Collection during Performa 2011. He is represented by Rodeo in Istanbul.

3. LAURE PROUVOST

“I want my videos to become a physical experience,” declares French video artist Laure Prouvost, “I like art that makes you reflect on your own experiences.” And physical they are— in her 2010 video The Artist, Prouvost tracks the frenzied path of a black ant, squishing it with one hand while holding a video camera with the other. The ant explodes under her finger and sticks to it, and in a macro shot, the insect’s twitching exoskeleton gets wiped onto a swirly pink painting by Prouvost. In an endearingly lazy French accent tinged with over a decade of living in London, Prouvost mutters something about needing to call her granddad, dialing his number on what appears to be a cardboard iPhone 3G display. Each successive shot rotates quickly, none of which lasts for more than a couple of seconds. A snapping hand leads into a millisecond of yellow screen, and next, a black screen with (sometimes misspelled) text: “THIS IS TO ATTACH GRANDMA UNDER THE TABLE,” and “AND ATTACH THE DOG BY ITS TAIL LIKE THAT.” Subsequent frames include a tour of messy shelves with broken sculptures and studio refuse (sometimes through which the artist pokes her finger, as if fondling it) and the visceral smashing of strawberries under a board; all the while, Prouvost mutters various phrases such as “I’m sorry it’s messy, I’m sorry it’s messy, but I wanted to show you everything…”

Laure Prouvost lives and works in London and is represented by MOT International. She has recently participated in Frieze Frame (2010) and Frieze Projects (2011) and held solo exhibitions at MOT International and Flat House, London, and Spike Island, Bristol. Prouvost won the GBP 10,000 Max Mara Art Prize for Women in 2011, the Jarman Award, and was also the principal prize winner at the 57th Oberhausen Film Festival.

4. TIMUR SI-QIN

Timur Si-Qin was born in Berlin in 1984. At the age of four he moved to Beijing, where, surrounded by his Chinese family, he promptly forgot how to speak German. Another move followed to Arizona, where Si-Qin spent most of his adolescence. He has since moved back to Berlin, where, not so surprisingly, he makes work about the language-less phenomenon of natural selection— how themes such as money, sex, family, and love continue to dominate our mental capacities, and how advertising executives direct campaigns toward manipulating these desires.

Si-Qin’s recent show at Berlin’s Société, titled “Mainstream,” superimposes natural flora onto posters of Transformers. The evil Transformers characters are notably sickly and slimy, built with rough, angular shapes, while the benevolent Transformers in contrast are healthy, upright and broad-shouldered— strapping young men, as it were. How far back do the associations between bad health and evil go? Here, Si-Qin posits that the narratives surrounding Transformers— an object of man’s construction— may not be so far from what we perceive to be “natural,” signified by all living things’ predisposition to succumbing to disease. Si-Qin’s November 2011 solo show at Fluxia in Milan, “Legend,” saw the artist extend his artistic production to include the gallerists and their families. Si-Qin arranged a day trip to a shooting range with the two Italian women and the father of one of these, who is a medieval reenactment hobbyist. True to Si-Qin’s fascination with the bio-determined narratives of violence and family, the group fired shots at the father’s medieval reenactment gear, which was later exhibited in the gallery.

Si-Qin is represented by Société in Berlin and has recently shown at Stadium, New York, and Kaleidoscope, Milan. With Estonian artist Katja Novitskova, he will open an exhibition at CCS Bard in April 2012.