MODERNIST MEMORIES OF SUFFERING: A TAIWANESE PERSPECTIVE

| April 19, 2012 | Post In LEAP 14

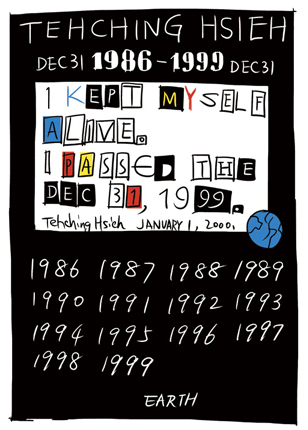

In Taiwan, clues to the Tehching Hsieh legend could originally only be found in fragments amongst brief, incomplete scatterings of text. As of 1986, after the artist’s year-long performance No Art Piece (or One Year Performance 1985-1986, New York, during which he made no art and abstained from discussing or viewing art of any kind), this information became ever more scarce. In view of this, the recent string of events— a press conference, a lecture, and a discussion— have caused a veritable buzz of curiosity within the Taiwanese art world, one that surpasses the general heat of interest around the artist, especially among the young people who make up a significant portion of his fans. Even more surprising, though, are the issues of interpretation which, after his long absence, have emerged conspicuously and in unprecedented fashion. The history of Hsieh’s bodily performances has been displaced to the extent that current scholarship regarding his work is dispersed around the world, a fact that directly draws analyses of American globalization. This article takes as its point of departure this forgotten period of history.

In 1987, the year after Tehching Hsieh’s year of artistic abstinence came to an end, 39 years of martial law in Taiwan approached its end. Young Taiwanese today would perhaps find it difficult to imagine that at the time Hsieh produced his first work in Taiwan, the island was locked in a tense political state of cold war, anti-Communist sentiment and martial law. In 1973 Hsieh presented this work, Jump Piece, which involved him jumping from a height of around 15 feet from the second floor of a building onto a cement surface, breaking both his ankles— an injury from which he to this day suffers repercussions. This bodily scar marked the first instance of his self-branding with the lofty mark of a “traitor,” at least until 1974, when Hsieh went drastically beyond Jump Piece by literally jumping (deserting) from a Taiwanese military ship on the coast of Pennsylvania.

It could be said that both of these scars are imprinted into the process of his self-enlightenment, which gradually turned into a desire to modernize the body, endurance art thus finding its focal support. We can now revisit this period of activity between 1973-1974, that time of cold war, anti-Communist sentiment and martial law: from jumping from a building to jumping ship to America, both demonstrate that under these stifling historical circumstances the “illegal” implications of Tehching Hsieh’s actions, from physical self-harm to the destructive relinquishing of his nationality, were in fact pronouncements to the world as he transformed his relationship with Taiwan.

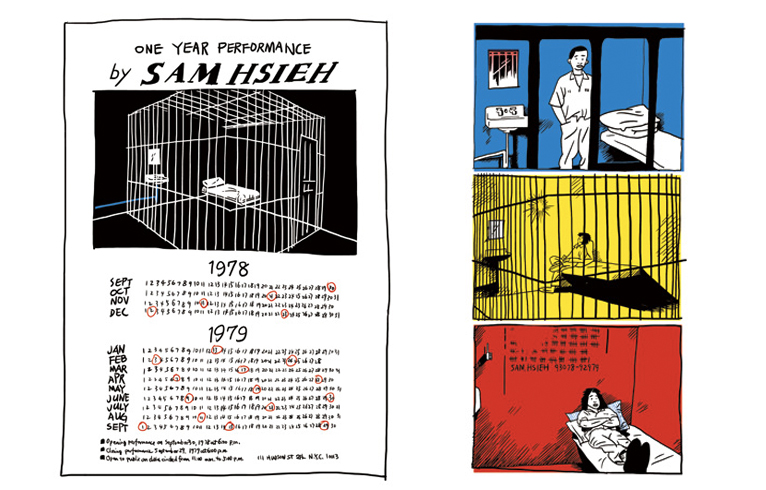

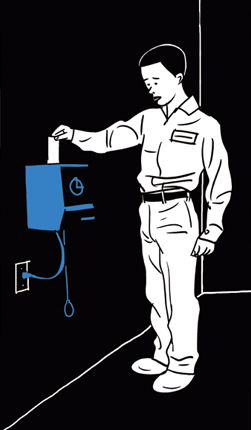

In 1978, Tehching Hsieh extended his application of physical harm through the works Paint Stick and Half-Ton: in the former he carved scratches into both of his cheeks with an artist’s cutting knife, and in the latter, bore the weight of half-ton limestone slabs, fracturing his collarbone. Following his defection to the USA, but before the beginning of the first of his One Year Performance works “Cage” (One Year Performance 1978-1979, New York), his worldview still rested on the separation of time and space, or perhaps, on the rupturing of the line between reality and non-reality. Though in the artist’s own words, “at that time I was in fact in the most dismal state” (Out of Now, p.330), the deathly works Paint Stick and Half-Ton were in fact part of a self-absorbed metamorphosis from within an laborious and lonely state of existence.

While still in Taiwan in 1973, Tehching Hsieh presented a painting titled Military Rank— a memory of his previous conscription to military service. “The canvas was divided into two rectangles, the lower rectangle was painted the grass-green color of the military, in the upper rectangle on a white background was written my conscript number.” (Out of Now, p.325) From both his own writing, and from interviews, we detect how rarely Hsieh talks about his time in martial-law-era Taiwan, to the extent that it seems intentionally played down. For example, he says: “In 1973 I gave up painting. I had no idea which direction to take. The atmosphere in Taiwan at that time was extremely stifling; there wasn’t a single opportunity to get hold of the exciting and inspiring avant-garde art of the Western world.” (Out of Now, p.328)

Tehching Hsieh doesn’t elaborate any further about that era which caused him to lose direction, though judging from the later performance work which featured his own imprisonment, the question is inevitable: in what kind of world is there a lingering memory of a yearning for the physical body? Even if in his painting Military Rank he had already enacted an integrated and self-conscious response to the things he had experienced in the real world, his own identity must have developed from social relations within the society that he and others actually experienced. But, in the end, Hsieh’s expression of military life under martial law only features his conscript number, as his name is tellingly omitted.

We still remember the martial law period: the White Terror, the atmosphere of imprisonment, the panic-stricken fear of carnage, the jitters and anxiety. Artistically-minded young people self-educated in loneliness and isolation, and a particular kind of intellectualism developed from indulgence in that isolation. As Tehching Hsieh himself says, his outlook developed out of the influence of Dostoevsky, Kafka, Nietzsche, and the story of Sisyphus. It could be said that these writers now form the fundamental tenets of Western modernism, but in relation to the oppressive atmosphere in which Hsieh lived, these works more likely became the fundamental tenets not of Western modernism but of its myths. After the lifting of martial law in 1987, both the political and scholarly world rewrote the history of that period, and many binary historical perspectives based on contrived methodologies emerged, including critical theories surrounding the historical development of modernism in Taiwan which were often founded on the wishful search for “freedom,” discussed martial law-era aesthetic values, and made revisions to artistic norms and aesthetic experience. This kind of scholarship degenerated into venerations of the past at the expense of the present, and it was exactly this kind of criticism that caused the fragmentation of the fundamental tenets of these issues, as it trampled over the painful memories of the genuine experiences of those who were trapped in this terrible atmosphere.

Little wonder, then, that when Tehching Hsieh was invited by Taipei Fine Art Museum to participate in a conference to mark the publication of Out of Now, the host’s focus stayed within a Western contemporary art context, constructed from the realization of Hsieh’s artistic dreams after his flight from Taiwan to New York. Similarly, in Out of Now, British writer Adrian Heathfield, during the development of his treatise on Hsieh’s performance work, focuses exclusively on Western modern art history, from which he draws a complete set of conclusions regarding the artist. This factor also helps us understand why Hsieh publicly states that his early performance in Taiwan, Jump Piece, was not at all a “good” piece of work. Although Heathfield approaches it as one of Hsieh’s “mysterious works,” both viewpoints come back to Hsieh himself— his desire to start afresh in America with a self-treatise and set of tenets that had no connection to those of Taiwan, which later began with his first One Year Performance in New York.

But when faced with an Asian/Northeast Asian/Taiwanese-born contemporary artist such as Tehching Hsieh, the need to begin from a local perspective, and arrive at an interpretation of the yearning for modernism in the artist’s bodily performances, is an issue that no critic from the same region should avoid. For example, when approaching Hsieh, whether or not to comply with his own theoretical tenets— to cut off his One Year Performances from his earlier performance works in Taiwan— becomes a crucial issue: not only is it something that cannot be ignored in the construction of a theory of Hsieh’s work, it simultaneously acts as an entry-point to reexamine the ways in which Taiwanese contemporary art discourse constructs and deals with issues. And indeed, over the course of Hsieh’s visit to Taiwan, during the numerous discussions which took place amongst scholars, this subject was completely ignored.

We must ask further: what is the meaning of the yearning of an Asian/Northeast Asian/Taiwanese-born contemporary artist such as Tehching Hsieh to modernize bodily performance? Art critic Chen Chuan-hsing’s book Melancholy Document (published by Lion Art) deals with this question. In the prologue he states: “even though originally in the West the development of ‘modernization’ and ‘modernity’ was essentially asymmetrical, sometimes intermingled together then torn apart, never before has this very phenomenon been postponed for such a great length of time. Is this a unique phenomenon of Taiwan’s cultural sphere?” When Hsieh stated his One Year Performance works all came from the same premise that “life is one long prison sentence,” he seemed to have replaced Chen Chuan-hsing’s question to Taiwan with an answer in the form of a physical image. Modern history contains many connections to the entrapment of the body, and if the Japanese colonial government brought their experience of modernization to Taiwan, it was focused on the “North Center of Affairs of Punishment” (later renamed by the Kuomintang as Taipei Prison).

Built at the end of the nineteenth century, this followed the Western Panopticon model, a specific prison building design which allows a warden to observe all inmates without them being able to tell if they are being watched. This ingenious, actuarially-designed structure, with its connection to power, became the first mold for modernism in Taiwan. This in turn illustrates that before Taiwan’s capitalist modernity produced individualism, it had already begun to produce a consciousness of the body from this prison. We know from Foucault that the use of a modern technological approach to implement ingenious and actuarial concern for the control of the body, and the gradual attainment of this control, is an important process in the development of the modernization of a society. Tehching Hsieh’s 1978 works Paint Stick and Half-Ton continued the bloody ceremonial nature that began with Jump Piece, as if the artist had initiated a kind of self reconstruction project, using self-harm as a means to cut himself free from the physical entrapment of Taiwanese history (a slave has no right to harm himself). These performances were thus self-dignified cleansing ceremonies, and their vigorous investigation later on within Taipei cultural circles and art colleges even better refutes this kind of oppressive entrapment inside and out. But by 1978, when he began the One Year Performance series, this stimulus had been replaced by something else, as New York became a backdrop for collective memory.

The 39 years of martial law imposed upon Taiwan by the Kuomintang government greatly strengthened the discipline of the nation by shackling its citizens’ freedom to think and act. During that period,Taipei Prison assumed a forceful function, publicly and nationally. Tehching Hsieh’s corporeality was steeped in this “conservative and tedious” environment, which not only dissipated within the stench of martial-law-era politics, but also contained within it the relation between modernity and the body brought about by the suppression of the essential tenets of history. To put it more simply, Hsieh’s corporeality was a yearning for freedom, or more strictly, an individualist statement within capitalism.

It could be said that the artist’s yearning for national liberty turned him into an illegal alien, or rather, in the closed atmosphere in which “there wasn’t a single opportunity to get hold of the exciting and inspiring avant-garde art of the Western world,” America simply became his Promised Land of contemporary art. So, his Jump Piece performances, from the harm of his body to the destruction of his nationality, express a simple yearning for freedom. During the period of their creation, the USA sent its 7th Fleet to defend Taiwan from possible attack; on the island its image as the protector was greatly perpetrated. Tehching Hsieh’s decision to choose America as his Promised Land, as someone perhaps practically alone in his knowledge of Western avant-garde art, could be entirely attributed to Chen Chuan-hsing’s so-called “unique phenomenon of Taiwan’s cultural sphere.”

Tehching Hsieh’s view of life as “one long prison sentence” of course includes the history of his own life. It both contains the wisdom of ancient Eastern philosophical thought and harbors the cry of one who has suffered great hardships. Both can be used to interpret his creative philosophy, and sufficiently illustrate his imbuing of the body with meaning. But in the body’s production of an ideological system, individualism begins with the realization of the existence of the consciousness of the self, and the body’s perception of pain, the shock this brings about (according to Descartes), and its close joining with the self-conscious mind is the process that finally completes it. That which emerges from great strife is the same as the suffering of imprisonment. So for Hsieh, regardless if in reference to his work in Taipei pre-1978, his work in New York, or his series of One Year Performances after 1978, the “prison sentence” he suffered in every case amounted to his pursuit of the struggle of the body with the perception and issue of physical suffering. Or, more specifically, it was all an attempt to reach his Promised Land.

According to Tehching Hsieh, whose life began in Asia/Northeast Asia/Taiwan, and who later reached his contemporary art Promised Land, “conceptually, my works certainly do not have a specific relationship with any time or place.” But, he also says that the development of his creative philosophy took place in the American city of New York, which perhaps implies that he prefers to cut his work away from the fundamental tenets of this period in Taiwan. Cutting himself off from physical pain, from the memory of the destruction of his nationality, from the cause and process of Taiwan’s change in its position in the world, his painful memories are nowadays his forgotten history. But perhaps this is exactly what Western contemporary art history needs: another fairytale of globalization.