SUI JIANGUO

| May 14, 2012 | Post In LEAP 14

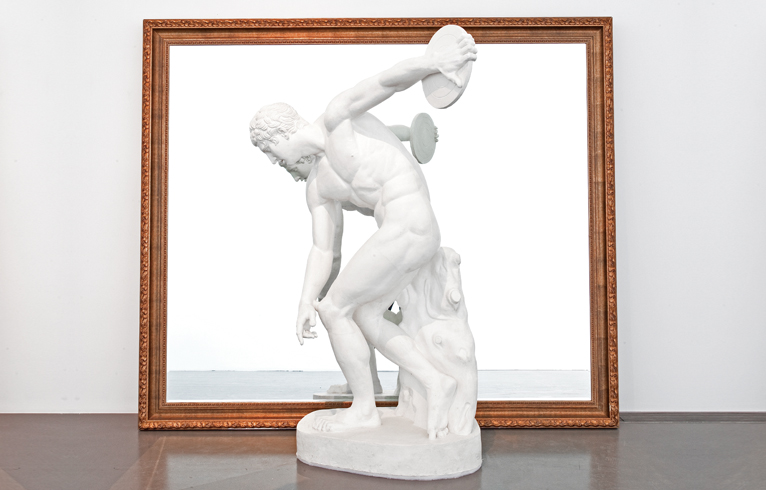

Sui Jianguo’s solo exhibition at Pace Beijing mounted the representative works of his various phases from the 1980s on, the earliest of which is a plaster cast sculpture from 1987, when Sui was still a student working toward his MA. The most recent of works on display is 2011’s bronze cast, The Blind. As it happens, these two pieces perfectly present both the transformation of the dimensions as well as the breadth of his methods for working with materials— both in terms of the medium’s dimensions as well as conception. As a matter of fact, the force behind nearly all of Sui’s pieces comes from the dissonance and resolution between these two extremes, and this is the reason why he has been able to maintain such dynamism and such high standards for so many years.

Even though there were 30 pieces altogether on show, for an artist as prolific and dynamic as Sui, whose identity is so diversified, it is difficult for this kind of mid-scale exhibition to comprehensively present all facets of the artist’s practice. Instead, it places emphasis on the intrinsic reasoning of artistic practice, impassively focusing on the creative state of the artist. Though including a print of The Legacy Mantle as well as drafts for The Shape of Time, it did not resort to the usual retrospective array of so-called documentation; like his works, this exhibition exercised restraint and circumspection, the artist’s subjectivity confined to the selection and classification of the works, including a sentence on the wall that merits repeating here: “Each of my works clearly and unequivocally seeks out the elements of the social backdrop of a particular time, but I am still trying to find a kind of method capable of sustaining itself and imbue it with the life which I have experienced as well as with some form of the world that I have confronted, although I fully realize that I am a long way from achieving this objective.” If we compare his treatment of the Mao jacket in The Legacy Mantle with the use of political symbols in pop paintings, we can better understand that Sui Jianguo’s emphasis is on inherent methods and forms, and not on external factors such as society, culture, and politics. Here, his Mao jacket has been treated as a material object— for its texture, the space it occupies, its mass, its weight and temperature— not only as an external political symbol. But precisely because of the particulars of the being-ness involved in the Mao jacket, the work possesses an even greater deal of introspection on societal, cultural, and political experiences.

To be sure, the creative state is by no means suited to presentation in a gallery space. This is particularly true of works like The Shape of Time and A River, which unfold over time and in the real world. But how to better present the transformations in art’s creation? Would an exhibition right inside the artist’s studio be any more appropriate? Anti-museum, anti-gallery, anti-collection, and anti-domestication of the system— these are the foundations of conceptual art, although there are not many people today who still take these notions seriously.

However, these factors have not harmed Sui Jianguo’s success. He has been one of China’s most important practitioners of experimental art since the 1990s. As an educator, too, he has promoted the liberalization of artistic ideas and practices. Sui has a considerable number of dynamic young artists as disciples, and although there are clearly differences among them, you can more or less see traces of their teacher in all of them. This point serves as fascinating proof of the diversity of Sui’s artistic practice— note that aside from the conclusions drawn by this exhibition, there are still many works that were deliberately left out, especially Sui’s pop art red dinosaurs. In this sense, perhaps we should take this exhibition as a self-selected “best of ”— a timely arrangement in stages of the understanding and construction of the self. Take, for example, the exhibition’s title, which is simply “Sui Jianguo.” Bao Dong (Translated by Caly Moss)