BOY: A CONTEMPORARY PORTRAIT

| June 8, 2012 | Post In LEAP 14

The title of this exhibition,“Boy: A Contemporary Portrait,” connotes something provocative. The combination of “boy” and “contemporary” deserves particular mention, opening up the kind of discussion that could either become elevated and abstract, or be summed up briefly and succinctly. The exhibition “politely refused” the participation of female artists, thereupon automatically presenting itself as some kind of mono-gendered self-reflexive study, involving both the curator’s understanding of preexisting works, as well as the responses of commissioned pieces. Though the exhibition boasts various interweaving threads, its complexity ultimately acts as a barrier to affective emotional involvement, and it seems but a moderate and efficiently arranged collective exercise, albeit one that maintains a consistent and refreshing appearance.

Contributing artists Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Wolfgang Tillmans’ personal, longstanding preoccupation with gender has formed their well-wrought practices, while American artist Fred Tomaselli’s recreation of newspapers and French choreographer Jérôme Bel’s video piece adopt the male sex as a sphere for more public discussion. The collective presence of these establishes a kind of composite whole, which, when set against the contributions by Chinese artists, examine the “male” identity from within a very different context, becomes by far the most interesting aspect of this exhibition.

With respect to the exhibition’s vision, Zhou Haiying’s decades-old black-and-white images and Mei Yuangui’s digital fashion photography, in both breadth of time and conceptual scope, offer little more than a superficial footnote: no matter if presenting the fit-and-healthy image of the male from the era of Collectivization or the twenty-first century mirage of the airbrushed muscleman, in their attempt to elaborate on the theme of the exhibition, these two small photographs seem merely to illustrate a historically prevalent lack of imagination towards notions of the male identity within Chinese society, their effect more akin to feeble sociological demonstration. Meanwhile, although originally created with no relation to this exhibition, Yang Fudong’s The First Intellectual and Liu Chuang’s Buying Everything on You possess the same intense characteristic, in that they both unconsciously present a localized impression of the social category of the Chinese male artist.

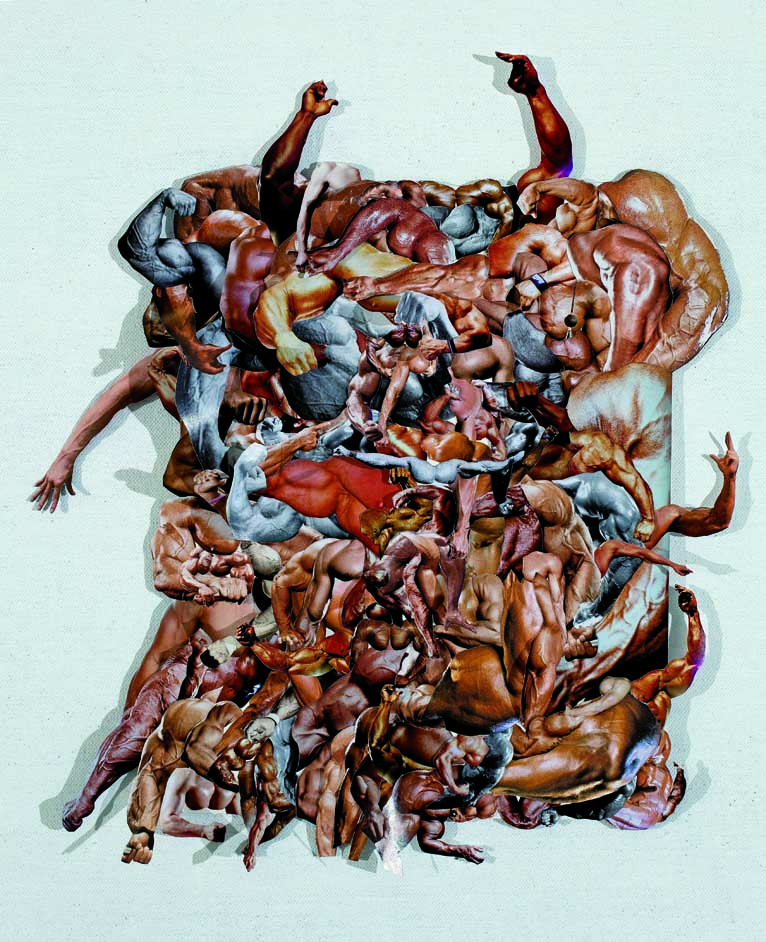

Guo Hongwei’s exhibition-specific collage is bold and lively, and although its all-too familiar technique of layering images of male torsos falls short of inducing any kind of strong reaction, its humorous execution will no doubt will bring a smile to many. Though inherently “genderless,” Cheng Ran’s video House of Hope comes off as an homage to the British gay artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman, especially as its plant-laden car is a clear response to Jarman’s journals, titled Modern Nature, and the use of a blue palette and sound design directly relate to Jarman’s Blue. The motivations behind and intentions of this work are more worth considering than its appearance: when a Chinese heterosexual male artist chooses Derek Jarman as an entry point into a discussion of the contemporary male, what kind of possible aesthetic and political questions does this raise?

Here, the exhibition acts upon the work as much as the works constitute the exhibition: Hu Xiangqian’s old work The Sun, when co-opted by the prerequisite “boy,” unexpectedly shook off its intrinsic associations with race and identity, thus displaying an example of one of Hu’s best talents: his ability to effortlessly cut himself free from association. His is the humor of testing and observing the most primal capabilities of the body, an impression emphasized by another of his more playful works featured here. However, Li Qing’s Images of Mutual Undoing and Unity-Duchamp, which makes sense within the artist’s overall thematic focus, appears here rigid, lacking vitality and pertinence.

But back to the “boy” theme, and the show’s attempt to “re-define the manhood of today.” Certainly a very interesting mission statement. However, after seeing the exhibition, articulating the meaning of “boy” is still a challenge, and our curiosity remains unsatisfied. He Yue (Translated by Dominik Salter Dvorak)