Yang Mian: CMYK | He Sen: Conversing with the Moon

| June 7, 2012 | Post In LEAP 14

There is quite a bit of overlap between Yang Mian’s “CMYK” and He Sen’s “Conversing with The Moon,” two solo exhibitions separated by the Chinese New Year. Both artists are graduates of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, both invited Lü Peng to act as curator, both opted for similar publication formats (each providing one exhibition catalogue and one collection of critical essays), and both were held in museums. Apart from these similar “credentials,” the most conspicuous overlap between the two occurs in the works themselves. In recent years, these two artists, with no apparent coordination between them, have shifted direction in their painting practices, turning their focus increasingly to the iconic images of traditional Chinese painting. For all of these reasons, the two are easily placed in the same category. Add to the list the fact that the two also both participated in “Pure Views” at the 2011 Chengdu Biennale, and this judgment seems even further justified. But at a fundamental level, are the current painting practices of Yang Mian and He Sen truly cuts from the same cloth?

If this is merely a factual comparison, then it can be said that the shift in He Sen’s painterly practice came a bit earlier than that of Yang Mian. At the end of 2004, He Sen began to tackle oil imitations of ancient traditional ink works by the likes of Li Shan, Ma Yuan, and Xu Wei— while at the same time gradually abandoning his work on his “Girl” series. Although “Conversing with The Moon” is an exhibition title brimming with allusion to classical Chinese culture and indeed corresponds to He’s new creative direction, the exhibition also carves out an entire floor devoted to his early painting practices. From the perspective of visual vocabulary and style alone, the works on this level can be divided into two parts: the first, He’s expressionist phase— representative of Sichuan’s New Generation— and the second, the “Girl” series of his photo-painting phase. Of course, this “exhibition within an exhibition” has been set up with the intention of providing a comprehensive introduction to He Sen’s practice, but within it, one can observe that retreat of passion which comes from having “seen it all before.” Perhaps it could be interpreted as the sort of cold composure that follows an artist’s redefinition of self and of the outside world.

If this is so, then “Conversing with The Moon” in the downstairs gallery is a pure product of that calm. Interesting to note is the exhibition design’s pursuit of a staged effect. All of the elements of a tranquil garden— rockery, pavilions, bamboo, and orchids— weave amongst the landscape towards the paintings. The coordination of three canvases on one dark wall is also done with similarly clear intention, or at the very least, they refer to three different styles of aesthetic romanticism: the bold and unrestrained, the whimsically graceful, and the perplexingly bizarre. Furthermore, under the spotlight, the three paintings exude the same brilliance as would a bright white moon against the night sky. Only, unfortunately, as He Sen’s works are based in the materiality of painted details, they are rendered glossy and flat. Perhaps given the devastatingly high-ceilinged exhibition hall, the artist and curator were hoping to at least get the audience involved, moving viewers simply with the force of an overall “classical” sensibility.

In another small exhibition space, the audience can observe up-close the way in which He Sen distinguishes the language of oil painting from that of ink painting. He doesn’t deny that he is an oil painter working in ink. He consciously seeks “harmony within difference”; generally speaking, he attaches great importance to the sensory experience of painting substance and texture. On the one hand, this has roots in his early expressionist style; on the other hand, it embodies the fetishist psychology of Chinese society. But He Sen stresses the planar component of his works as well— levels, and not just surfaces— by flattening and layering, techniques he often uses. The two methods together give his recent work the impression of a collage, a visual experience which strongly attests to He Sen’s focus on imagery. But in contrast to several previous shifts in his painting style, his persistent devotion to the concept of individualism in recent years, as emphasized by “Mogu,” is not so much a harkening back to traditional Chinese aesthetics as it is He Sen’s repeated retraction of the autonomy of the personal dimension— and it is precisely this autonomy that possesses a truly worldly psychological connection to Chinese aesthetics itself. Within this classical sensibility, just as it was with the great masters of classical Chinese painting, the language of form becomes the very content of artistic practice.

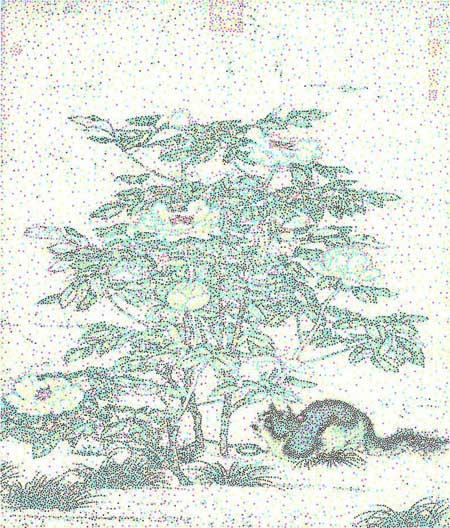

In contrast with He Sen’s “Conversing with The Moon,” all that Yang Mian’s solo exhibition “CMYK” at the Shanghai Art Museum shows is the series of works to which the exhibition title refers. Yang began the “CMYK” series in 2009, creating works intuitively similar to the pointillism of the Neoimpressionists, but his dotting brush strokes draw from an alternate fountainhead, calling upon something much closer to the color separation system of a modern printer than a color study of natural environments. Even those audience members who do not understand what “CMYK” represents can experience the enormous visual disparity it produces: from afar the image is crisp and clear, from close-up the image is a mess of dots devoid of spatial relationships. Yes, the work expresses its idea simply and directly, but a high degree of effort was spent to produce such simplicity. These are manual brushstrokes that attempt a feat of mechanical production: the singular challenge of mastering the struggle of the painting process itself.

Beginning with the “Standard” series, which he started in 1998, popular images were and continued to be the primary object of Yang Mian’s attention, for him the landmarks of consumer society and central subject of his creative expression. Though he would adjust his themes based on the current social issues that concerned him, he made almost no fundamental changes to the painterly language he used to address them. It was always his “standardizing” flattening technique, a painstaking effort to exact a “color sample for society.” Yang’s earlier works are always reminiscent of commercial advertisements, and, in fact, this impression is not altogether inconsistent with the original intention of the concept he established. What he constantly highlighted was precisely an experience of the everyday in terms of a “standardized” landscape of the everyday. The only problem is that the landscape his “expressionist brush” set out to critique was far bigger and more powerful than the work itself, and that relationship between “going undercover” and “assimilating” has always been a subtle one: after a while under those kinds of circumstances, a work will inevitably become a victim of Stockholm Syndrome.

From this vantage point, Yang Mian’s “CMYK” series has not escaped the old logic after all; it has merely switched out popular images for classical ones. But, through the conversion of context, Yang has once again clarified his relationship to images. This became especially true when, after he began to focus on traditional paintings, a particular brand of irony that had gradually come to its last legs finally sprung up anew. With this exhibition, Yang Mian has in fact enforced a distance between the eyes of the audience and the images they behold, but this impenetrable experience of removal is best understood not as an expression of difference between “the image” and “the original” but rather as a targeted portrayal of the cultural dilemma we currently face: that of the enormous, conspicuous hollowness that is the current trend of “retro” in art— which, other than the fact that it is popular, seems to have absolutely nothing to add. In this light, the painting practices of Yang Mian and He Sen are entirely opposite in the forces that drive them and the principles they embody. Ultimately, the two are not alike in the slightest. Sun Dongdong (Translated by Katy Pinke)