THE MAKING OF REMAKING: RURAL POLITICS, OBSERVED

| November 20, 2012 | Post In LEAP 17

“Kunshan—Under Construction,” an intervention-style research project marrying art and society, began in 2010. The project observes and investigates China’s New Countryside program of rural construction. The specific locale of the project is Kunshan New Village in Chengdu’s Shuangliu county.1 The multidimensional, integrated art intervention project has included field research, on-site creative projects, short-term themed workshops, interdisciplinary symposia, themed exhibitions, and more. The spontaneous origins of the project have created two parallel channels for discourse: a reality- and history-based critical intervention, and a constructed system of reflexive artistic practice.

More than one year of field research, conducted beginning in 2010 by artists from Chengdu’s Experimental Workshop, constitutes the principle cornerstone of the sustained implementation of “Kunshan—Under Construction.” These investigations have shed light on a variety of land-related issues: the contorted relationship between the new and old villages of Kunshan; the government-led shift toward community housing; the changes in land use and the local economy; the relocation of local residents; and so on. The surveys constructed a system of discourse based on interventions on the emotional level, forming a framework for reflection and creativity. Local chronicles and emotional responses were the channels through which the project came together. Beginning in 2012, on-site creative interventions emerged as a crucial new aspect of the project.

At six in the morning on April 30, 2012, Mr. Chen, a mushroom grower from the outlying provinces, embarked on the second phase of his workday: transporting the mushrooms he had just picked to the point of sale. It was a special day because Chen was joined on his truck by a few other mushroom growers— his brothers. Around 2008, the brothers had come one by one to Kunshan to grow mushrooms. Following the Wenchuan earthquake, the government withdrew the preferential rights promised to such farmers, instead awarding them to disaster-area planters. As a result, in the five years since, Mr. Chen and his brothers have barely managed to make ends meet, and their incomes are far lower than what they might earn as migrant workers elsewhere.

The artist Cao Minghao met the truck at 6:30 as planned. In accordance with the artist’s requests, the truck proceeded aimlessly down the road as the artist interviewed the mushroom growers. They provided a geographical account of their lives since leaving home to find work in the 1990s: stops in Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Shanghai, Beijing, Xi’an, and other hot spot cities in various stages of development. This interview was an on-site component of Cao’s project, An Individual’s Geographic Annals 2. His work provides a fragmentary intervention into the New Countryside economic structure that takes Kunshan New Village as its sample and the experiences of migrant workers as its starting point. Cao’s work falls within the larger scope of the surveys that make up the first phase of the Kunshan project. He observes the faint vestiges of family cooperation among a migrant population whose future prospects have been hemmed in and imperiled by ever-changing government decrees and outside investment in the market.

Cao Minghao’s interviews were not the only art activity to take place on April 30 in Kunshan New Village. From early in the morning until 9:30 at night, nine artists engaged in various interventions in different parts of Kunshan village. The collaboration of these artists from Chengdu and Chongqing was part of the social intervention art project, “Independent Research Project: Kunshan—Under Construction,” hosted by Chongqing’s Organhaus Art Space and initiated by Experimental Workshop, a Chengdu artist collective. The events of April 30 were part of a workshop with the theme “Labor and May Day.” (Participating artists included the members of Experimental Workshop as well as Chongqing’s Cell Group/Dong Xun+Shan Yang, Liu Weiwei, and Liang Jiancheng. On-site works included Pink Suggestion Box, Kunshan Sports Meet, Communal Canteen, and May Day Labor Fair.)

Experimental Workshop is a creative group established by artists including Chen Jianjun, Chen Zhou, and Cao Minghao, all of whom have childhood memories of the countryside. The roots of the project can be traced to the common experiences of everyone born in the early 1980s and before. In fact, the gap between China’s cities and countryside is far greater today, even though restrictive urban and rural residence permits were implemented in back in 1958 and the right of freedom of movement was quietly excised from the constitution back in 1978. It is farmers like these, kidnapped by the government and locked in the fields, who have borne the brunt of the aggravated fracturing caused by China’s urbanization. A tide of migrant workers rose in the 1980s to meet the massive demand for cheap labor fueled by urban development. The tremendous disparity between city and country— compounded by the dire economic situation wrought upon the peasantry by taxes, medical expenses, corrupt cadres, and public works projects— led wave after wave of peasants to leave their ancestral homes without looking back.2

In so-called “naked villages” populated only by the elderly and underage, minimal economic activity became the new norm. Remittances from family members gone to work in the cities also became an important component of the rural economy.

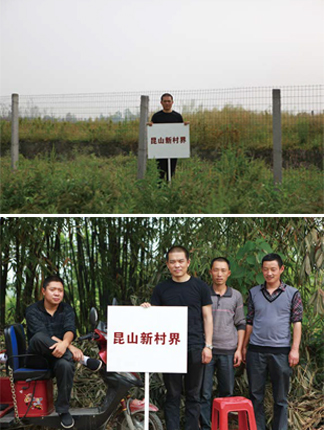

At ten in the morning, the artist Chen Jianjun, holding a sign with “Boundary of Kunshan New Village” written on it, initiated his contribution to the workshop, 2.92 Square Kilometers (Kunshan village is 2.92 square kilometers in area). Beginning at the village boundary, the artist walked approximately six kilometers southward, through Kunshan village as well as the neighboring villages of Yanggong, Wenwu, Tianlin, and Gonghe. Upon seeing the sign in his hands, some villagers mistook him for a government surveyor. Residents of the various villages offered a variety of opinions on the subject of Kunshan New Village, which had been designated by the local government as a “New Countryside Pilot Region.” The result was a direct dialog between real events and the artist’s predictions. More-so, it was an on-site self-evaluation of this sample of the New Countryside, an experiment in government policies.

The rural development experiment in Kunshan is a direct result of the “Building a New Socialist Countryside” initiative ordained by the Fifth Plenary Session of the 16th Central Committee. Macroscopically speaking, the project is intended to use new rural construction to increase the incomes of rural laborers. Increased incomes mean increased buying power and therefore greater domestic demand, the solution to China’s present overproduction crisis. Thus is rural construction now addressed with an unprecedented degree of strategy. Overall, China’s countryside in fact remains characterized by a small-scale, highly decentralized peasant economy in which land is divided into tiny parcels. Making efficiency and profit the goal of Building a New Socialist Countryside inevitably entails a comprehensive reorganization of the status quo. Those tiny parcels had to be collected together, necessitating the construction of community housing. Grouping together peasants who were previously scattered in all directions had the effect of opening up more land for cultivation and facilitating more convenient management. Kunshan New Village is the concrete result of these ideas. Small Western-style houses and apartment buildings built according to norms of urban construction replaced the courtyard compounds previously commonplace in the countryside. Of course, the reform of living spaces means more than merely replacing old houses with new ones. Changes in space mean changes in lifestyle. The very real transformation of rural culture— including habits, customs, and ways of thinking— is the true cause of apprehension and anxiety here.

At eleven in the morning, Chen Zhou arrived at Kunshan New Village pushing the eternal resting place he had designed. Thus was his art project revealed: the artist became a salesman, introducing and promoting to the villagers his mobile grave, Everlasting Pavilion. The grave comprised a miniature pavilion of the sort commonly used in burials in Kunshan mounted on a wheelbarrow-type cart often seen in western Sichuan. As the artist offered to sell this “product” at cost— 720 yuan— he drew a crowd of curious onlookers. A few asked questions. The logic behind a mobile permanent resting place lies in the government’s forceful implementation of its cremation policy, which is intended to save land for agriculture. (The absurd thing is, implementing the cremation policy has failed to achieve the goal of preserving agricultural land by changing customs. After the deceased are cremated, their children usually bury them anyway.)

Another reason behind Chen Zhou’s mobile grave is the disinterment and relocation of the family burial sites necessitated by the reorganization of all those tiny parcels of land. Kunshan New Village has even set aside some temporary burial sites, which will allegedly again be relocated once the construction of the new village is completed. The government’s rural burial policy is more than simply a conflict over land utilization rates. By interfering with the cultural and familial bonds of village culture, the policy has become one of the most troublesome aspects of the rural development program. Compulsory cremation constitutes an existential assault on the legitimate traditional burial practices of the countryside. By weakening the cultural identity of rural society, the policy accelerates the overall disintegration of village communities.

The execution of “Kunshan—Under Construction” as a large-scale project has repeatedly raised questions salient in both art and society. In essence it is an art intervention project, which tells us something about how to observe and assess this dynamic location. Art that takes a concrete reality as its primary discursive object always raises the question of what is primary. It is a question about art, but it is also a question about values. Preserving the openness of the project; emphasizing the differences within the plurality of artistic perspectives; refusing to plan or predict the results of the interventions, which in fact are formally micro-interventions or non-interventions; rejecting the tendency of artworks to become spectacles or objects of consumption; settling and framing the internal logic and discursive subject of each artist’s works; all of these are methods, but they are also positions.

China’s rural problem is a systemic problem. Its complexity lies in the natural rift between the reality of the widespread small-scale peasant economy and the core goal of economic maximization that lies behind the New Countryside project. It will take a lot of time for the countryside to digest this dramatic transition away from government policies prevalent since the 1980s. Consequently, it can be predicted that the activities of artists in this village will generate responses within two systems: first, the artistic practices that constitute the project will shape a new “isomorphic” reality as they interact with their environment, creating new topics for discussion; second, the interventions of the individual artists will fuel the discourse of their own artistic orientations. At the same time, a specific context of situation will eventually emerge in Kunshan as a result of these independent art projects, joining the artists’ works in a network of intertextuality.

Note: The discussion in this text of the New Countryside issue draws in part on The Background of Building a New Countryside by Wen Tiejun and The Past, Present and Future of Building a New Countryside by Shen Duanfeng.

1 Kunshan New Village is located along the Jinma River in southwest Shuangliu county near Chengdu. It is six kilometers from Shuangliu Village, and ten kilometers from Chengdu. It has become a pilot region for land transformation in Sichuan province, a “model village” for the province’s New Socialist Countryside initiative, and one of the “Top Ten Most Prosperous Villages Nationwide.”

2 The migration away from the countryside that began in the 1980s has deeper roots in state-level attempts to solve the threefold issue of rural industry, rural land, and rural people from outside the actual countryside. The primary focus of these attempts was placed on establishing a system for residence permits (away from the countryside), developing non-rural industry, constructing small villages, and diverting the rural workforce. However, the sheer size of the rural populace rendered these efforts futile, directly leading to a threefold rural crisis instead— as well as the subsequent passive reforms in government taxation.