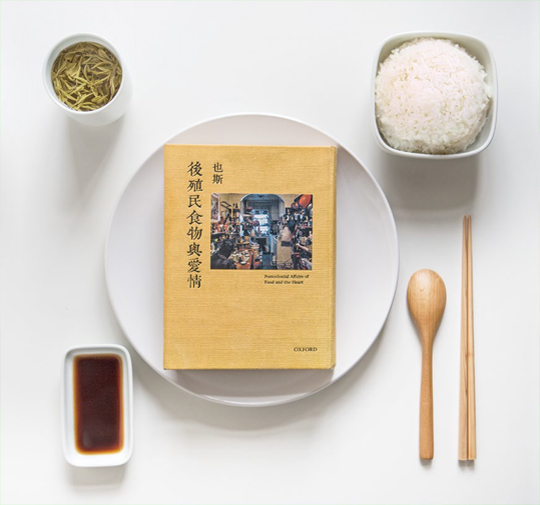

POST-COLONIAL AFFAIRS OF FOOD AND THE HEART

| May 22, 2013 | Post In LEAP 20

SIXTEEN YEARS HAVE passed since the Hong Kong handover in 1997. The writer Yesi, whose real name is Leung Pingkwan, was born in Guangdong in 1949 and grew up in Hong Kong. Over the past 16 years, he has mentioned his desire to “write about Hong Kong in earnest” on more than one occasion. This aspiration has been realized in a volume of short stories written over the past 10 years.

What did he write? The title, Postcolonial Affairs of Food and The Heart, naturally calls to mind prevailing Western critical theory. However, Yesi adopts a lower visual angle: the truly commonplace matters of love and food. His prose, like his poetry, is light and refined. Each character in the book is both the protagonist of his own story and part of the background of the stories of the others. The components of this winding cycle resemble the various chapters of a longer work while retaining the quality of verisimilitude. This structure does not come from the formal unity of Western fiction such as Calvino’s Invisible Cities. Rather, it is built on the basis of the relationships between the characters in the stories. The 12 stories feature the interwoven lives of a group of intimate acquaintances. Roger, an American college professor, and Ah Su, his young girlfriend, forage their way through Tokyo, facing the thoughts and feelings of real life. A group of old friends reunite in Europe and undertake an arduous journey to sample the famed cuisine of Aibre. Here, Yesi adds a predictable plot twist, transforming it into a poignant ghost story in which the Japanese Bushido tradition of keeping appointments with the pain of death is evoked by the metaphor of a last supper. There is also the touching tale of the food critic Lao Xue, who ceaselessly researches food and ponders love. Having long planned to write an all-encompassing compendium of food, he has tasted everything there is to taste. According to Yesi, “food connects many human feelings and relationships, connects our memories and our imaginations.” Food provides an important symbol that enfolds multifaceted cultural and material implications.

Of course, this book also discusses issues of identity. Some people see 1997 as Hong Kong’s return to its natural parent— the starting point of its post-colonial future. Attaining a new vitality amid this transition has become a core issue in modern Hong Kong. But how should the people of Hong Kong see themselves? Rather than accept the “Greater China” concept, that blood is thicker than water, would it be better to say that the two have been apart for too long, and each has its own new reality? The people in these stories vacillate between emigrating in favor of feasting on Western food or sticking around to face a new and improved Chinese cuisine. Yesi’s protagonists rarely take initiative. They tend to be led along by the times, or to retreat into pockets of history. Though they are awkward, they are also dignified. It is not much of a stretch to draw a connection between the metaphor of their urban vicissitudes and the negative liberty described by Isaiah Berlin.

Yesi sees hope in the resilience, flexibility, and expansiveness of Hong Kong people. Not all of the stories take place in Hong Kong; Macau, Japan, and Europe form parts of the backdrop. But throughout these characters’ permutations of gender and nationality, their Hong Kong-ness is essential— this is naturally a gift of history. In Chinese literature, it seems that only Hong Kong writers have the facility to write from the first-person perspective of Westerners. Similarly, bizarrely, Hong Kong is the place where Westerners seem to remain the longest without learning any of the local tongue. Thus these awkward experiencers of the local enjoy a nuanced involvement with Hong Kong’s neither-East-nor-West identity. Under Yesi’s pen, these denizens of the new Hong Kong face a century of colonialism and walk backward into the new millennium. They endure their circumstances through their stubborn attachment to Hong Kong’s unique cuisine and persevere through the specious and superficial. Although it does not come easily, they manage to carve out their own niche.

Rey Chow introduces the concept of “the transplantability of culture” in Writing Diaspora: Tactics of Intervention in Contemporary Cultural Studies, her treatise on Hong Kong, negating the essential question of Hong Kong identity and calling into question the cultural forbearance wrought by historical colonial anguish. In Yesi’s short stories, the orientation of Hong Kong’s memory, culture, and sense of belonging presents itself within the sundry and quotidian details of love and cuisine— all in the name of food. Herein lies the fierce, vivid, and everyday resilience of Hong Kong identity, insubordinate to any and all dehumanizing doctrines. (Translated by Daniel Nieh)