TOKYO 1955-1970: A NEW AVANT-GARDE

| May 10, 2013 | Post In LEAP 19

In the 1953 Another World, a newly-nuclear citizenry comes to the rueful realization that they “should have been more suspicious of God’s gift of nuclear power.” A collaboration between Jikken Kōbō visionary Kitadai Shōzō and composer Yuasa Jōji, the nine-minute “auto-slide show” syncs a projection and tape recorder to “animate” Kitadai’s neo-Constructivist compositions. The tale culminates in a spectacular power plant explosion that destroys not only the city, but the entire planet, sun, and surrounding galaxy. As for God? The lonely deity is left “in a state of boredom,” relegated to having to scheme up yet another world.

While on the surface a whimsically animated parable, Another World arrives at a particularly pointed moment in Tokyo’s history. By all accounts, the Tokyo of the 1950s may have felt like “another world,” but it still carried with it the psychological imprint of recent devastation. The city, all but leveled by war, had bounded back with remarkable resilience, rebuilding in near record time. In 1952, the government had already declared the postwar period “over,” ending the Allied Occupation and kicking off an era of rapid and resounding economic growth. Industry was not the only thing booming; in little more than a decade, Tokyo’s population had doubled in size, passing the 10 million mark by 1962. This unparalleled development did not come without its fair share of social upheaval. In finding new ways to live and work, the newly democratic citizenry had to confront the limits of their postwar bodies, which did not look, or act, or break down like the bodies of the Empire. Putting the body back together again required also putting together how that body behaves, particularly within the larger social organism. Here lies the crux of the Museum of Modern Art’s “Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde,” a compact survey organized by curator Doryun Chong in cooperation with the Japan Foundation. The exhibition is physically prefaced with an atrium display dedicated to the Metabolist Group, a collective of progressive architects, critics, and designers who advocated Tange Kenzō’s organicist approach to urban planning. Digital renderings of never-realized proposals like Isozaki Arata’s “Cities in the Air” (1960) or Kurokawa Kishō’s “Helix City Plan for Tokyo” (1961) imagine the future metropolis as a series of modular units installed along a flexible, expandable axis. The atrium’s adjunct wall is plastered over with a blown-up black-and-white map of Tokyo’s city center. A joint effort of Shigeko Kubota and Fluxus artist George Maciunas, the map plots the activity of the 1960s collective Hi Red Center, whose interventions mainly occurred in and around the Yamanote Line that runs along the civic spine. The exhibition openly emulates this structure, repurposing three sixth floor galleries as a type of condensed vertebrae, with pockets of activity sprouting outward in uneven intervals. This model allows the curators to break from a chronological narrative to group works according to professional or stylistic associations. While this tactic may knowingly oversimplify or even misidentify certain artists whose practice may not readily conform to any given movement or manifesto (Yayoi Kusama, for example), the end result is a rough sketch of a still-recent frontier of art history.

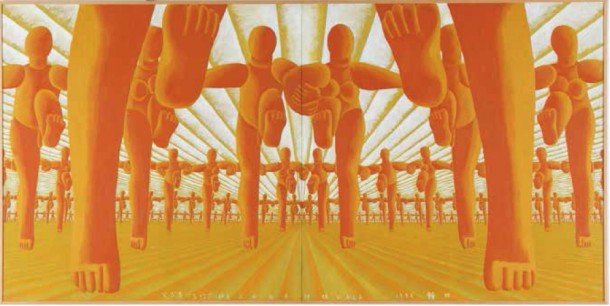

Mounted on a freestanding wall directly facing the exhibition entrance, On Kawara’s 1956 Stones Thrown is an oddly-shaped canvas, rectangular but for a dramatic dent in the upper right corner, as if crushed by the weight of its content. The painting depicts seven thick tires treading side-by-side over scattered sticks and stones on a rounded red-brick road. Speaking to the futility of political resistance, these stones set the tone for a room full of works primarily concerned with piecing together the body broken. If Social Realism had been the mandated mantra of the Allied Occupation, in the early 1950s, artists were willfully recuperating the Surrealism that had reigned before the war. Of course, the “exquisite corpse” found itself drastically reinterpretated in the wake of Hiroshima. A wall of drawings and aquatint etchings by Hamada Chimei gives a grotesque and gruesome portrait of a dismembered generation, while Nakanishi Natsuyuki’s Map of Human (1959), shapes the contours of a fallen figure using seams of dotted T’s, like so many stitches across skin. Ishii Shigeo’s 1956 oil on canvas Acrobatics stacks strained bodies into a type of human scaffolding, topped by a proud orangutan, its arms crossed and a self-satisfied smile stretched across its simian features. The repeated figures of Ay-O’s powerful Pastoral (1956) march— elbows locked, legs cocked— in seemingly infinite, ocher-colored rows, emanating from an uncertain horizon. It is at once an onslaught and a body count, an overpopulation stripped of humanity altogether.

The second gallery introduces the thematic grouping of the “cross-genre”; more than a catchall categorization, this intermedia art treated boundaries between artistic genres as flexibly as those between the human bodies of the previous room. This interdisciplinarity was exemplified by Gutai (whose name translates to, fittingly, “embodiment”), formed in the mid-1950s under the leadership of Yoshihara Jiro. Gutai debuted in Tokyo with a 1955 exhibition that included Motonaga Sadamasa’s Work (Stones), a collection of painted stones studded with plastic straws, as well as Shiraga Kazuo’s landmark performance, Challenging Mud. In a photo, the artist is nearly indistinguishable from the earth he is wrestling. Under the umbrella of the intermedia, the exhibition structure begins to bear more resemblance to the clusters of the Hi Red Center map than to the clean lines of the Metabolists. In one niche, there is a sampling from the Fluxus-friendly Sogetsu Art Center and its symphonies composed of written instructions (among them, Yoko Ono’s 1964 artist book Grapefruit). The section on Jikken Kōbō (Experimental Workshop) pulls together an elegant showing of this “Bauhaus without a building,” including Yamaguchi Katsuhiro’s vitrines; Kitadai and Ōtsuji Kiyoji’s photographs for Asahi Picture News; and Matsumoto Toshio’s mesmerizing 35mm film Bicycle in Dream (1956), which was made together with Yamaguchi and Kitadai and in collaboration with Tsuburayu Eiji, the special effects technician responsible for Godzilla.

Further along, displays on Hi Red Center, Zero Dimension, and the impounded objects from Akasegawa Genpei’s 1,000 Yen Note Trial question existing models of citizenship and social behaviors. These later collectives were loosely grouped together under the denomination “Anti-Art,” a movement defined not so much by stylistic properties as by opposition to “official,” state-sponsored art. The Yomiuri Independent (1949-63), an annual exhibition at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, gained notoriety as the platform for Anti-Art at its most extreme. If earlier concern had centered around restoring a body broken by war, these artists indulge in a selective, overtly-sexualized recuperation of anatomical elements (see Yoshimura Masunobu’s genitally studded Two Columns [1964], or Kudō Tetsumi’s net of ensnared “phallus-chrysalis hybrids”). A quick, glib nod to Japanese Pop Art and the figurative painters Nakamura Hiroshi and Tateishi Kōiji leads into the third gallery, where photography and works on paper explore the body restored. Here the sampled-psychedelia of Yokoo Tadanori’s posters faces off with the gritty realism in photographs by Fukase Masahisa, Hosoe Eikō, Tōmatsu Shōmei, and Moriyama Daidō. In Moriyama’s Japan Theater Photo Album (1965), a man with a shaved head and a scant brow crouches on his hands and knees, echoing the posture of the mangy stray dog of the artist’s celebrated Misawa (1971), which hangs atop the other images, recalling the proud ape from the first room.

Once the body has been restored, attention shifts to the objects it encounters, with the quiet, visual reprieve of Mono-ha (School of Things) and the sculpture of the late 1960s and early 70s. Takanatsu Jirō’s “Oneness” series refills troughs of concrete or wood with their respective remnants, while the four charred wooden stumps of Narita Katsuhiko’s SUMI (1968/1988) confront Lee Ufan’s Relatum (1969), which is spelled out through three large stones, chalk, and an extended measuring tape. These stones know how to behave within the institutional setting, preferring the individual experience over the collective. But as this exhibition proves, it takes rebuilding the collective to be able to move past it. Kate Sutton