THE RIGHT TO SPEAK, REPRESENTED: GRASSROOTS ART IN CHINA, 1950-70s

| December 16, 2013 | Post In LEAP 23

FROM THE 1950s through the 70s, propaganda art was valued as a crucial weapon for political struggle. It was an effective way to mobilize the people, in particular, peasants and workers who, at the core of society, constitute a powerful force. This social class was called upon to employ art as an expressive tool. When the People’s Republic of China was established, grassroots art was encouraged and promoted as part of educational and mobilization programs, which resulted in many a climactic period of creativity.

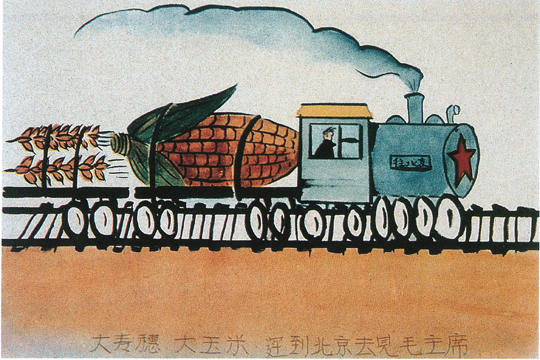

In 1958, a mass mural movement was initiated under the official guideline to “Gather up all forces, aim high and achieve greater, faster, better and more economical results in building socialism,” alongside the foundation of cultural programs implemented in the countryside. Murals predominantly promoted the official guidelines, the Great Leap Forward, and the ideological slogans of the Three Red Banners. In addition to large-scale paintings of political slogans, many murals depicted an exaggerated and mythologized view of harvest and bountiful production. Many peasant artists used amateur techniques and complemented their paintings with lines of poetry and prose.

Cangli County, Hebei Province, provided an early example of the national mural movement in action. High school graduates, young girls, and old folk painters joined the movement. Determined to establish a new way of seeing new things and people, they painted the scenes of production increase, improvements of daily life, and strong and energetic people of the Great Leap Forward. Another “mural county,” Pi County in Jiangsu, boasted 15,000 farmer painters by August 15, 1958, and a total of 180,000 murals on display; 50 percent of buildings in the county hosted one to five murals. That year, the ninth, tenth, and eleventh issues of the magazine Art also published in-depth coverage of the People’s art movement, including the features “Farmer Murals,” “Worker Art,” and “Warrior Art.” Theorists eagerly published reviews, while publishing houses and other public cultural departments proactively supported the movement. Many counties, cities, and provinces joined the movement, and with high aims, the mass mural movement flourished nationwide. The quantity of murals created during this period reflects their great contribution to a genuine leap forward in culture and production.

After the Great Leap Forward, this popular art movement officially came to a close. The peasants of Hu County in Shaanxi, however, continued to produce paintings under the guidance of art professionals. With the 1963 socialist education movement, the county’s mural movement rapidly developed after organizing the exhibition “Three Histories” (family history, village history, and social history). The movement reached its golden age during the Cultural Revolution in the 1970s. The works of the peasants of Hu County were selected for the annual National Art Exhibition, printed in catalogues, and exhibited at the China Art Museum as well as in many other countries worldwide. These paintings were characterized by their full composition, vibrant colors, depiction of multiple people, and impressive scenes that communicated idealism and warrior’s zeal. These works were created by members of the People’s Commune: women, youngsters, senior citizens, the Party branch secretary, the group leader of production, the People’s militia company commander and accountants, and so forth. The preface of Paintings by Farmers in Hu County, published by People’s Art Publishing House in June 1974, describes, “They hold their plows in one hand, and a paint brush in the other. In accordance with the Party’s guidance, the people of Hu County praise socialism and their new village, and celebrate the great success of the proletariat’s cultural revolution. They criticize reformism and the capitalist class.” The size and quantity of paintings created by Hu County cannot compare with those of the Great Leap Forward’s mural movement, but these paintings demonstrate a higher quality, and both a preservation and professionalization of farmer mural aesthetics.

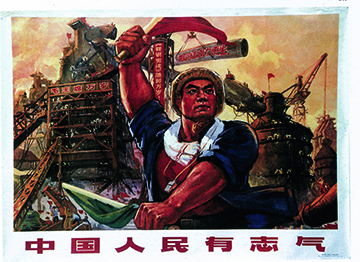

Shanghai, Yangquan, and Luda are well known for art produced by workers during the Cultural Revolution. On October 1, 1974, the National Art Museum of China opened the exhibition “Shanghai, Yangquan, and Luda Workers Painting Exhibition.” An article commented, “These artworks represent something new that has sprouted from the proletariat’s cultural revolution and Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius Movement. The exhibition is a microcosm of the amateur art activities of farmers, workers, and soldiers nationwide.” The worker paintings did not develop aesthetics as distinct as the farmer paintings. They consistently illustrated the class struggle and the Communist agenda. Workers in these paintings typically exhibited thick eyebrows, large eyes, strong arms, and an aura of great will. These traits constituted the classic model of the worker as hero.

The farmers’ fantastical and exaggerated depictions of the Great Leap Forward and the Communist vision, as well as the worker paintings of “Learning from Dazhai in Agriculture,” “Learn from the Industrial Role Model Daqing,” “Class Struggle,” “Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius,” and other thematic works expressed strong political messages. Why have peasants and workers displayed so much passion in artistic creation and political participation? The reason is closely bound with the art and political propaganda system of public cultural centers and clubs established by the Communist Party post- Liberation. These organizations supported national political, economic, and cultural developments by playing a critical role in affirming national ideology. In addition, Party organizations of all levels frequently organized study groups and advancement classes to improve the skills of peasants and workers. These programs were often led by a teacher who would provide students with professional help and guidance on what to draw and what not to draw, according to the teacher’s understanding of the national political agenda. Interestingly, under the political atmosphere of that time, these professional art teachers were targeted for criticism and reform. Teaching and promoting national policies and ideology was their way of atonement. Peasants and worker groups kept a distance from them, reluctant to accept their teachers’ potential bad influence on political and formalistic characteristics in their work. All officials, the people, and their teacher gave their opinions of art. These, in turn, culminated into a collective piece of work realized at the hands of peasants and workers.

Although peasants and workers produced highly political art, it is worth contemplating their true level of participation in and understanding of the political movements praised in their work. Hu County farmer painter Liu Zhide said, “We painted what the party told us to paint.” For ordinary people, messages communicated through political propaganda were considered the will of the Party and Chairman Mao. They were unaware of the political complexities within the Party. Although many peasants and workers organized theory classes and studied abstract political language, their understanding of theory was rough and distorted. Liu Zhide’s Old Party Secretary depicts a village officer who studied intently between periods of labor. This sketch, set in a factory, was promoted as a direct illustration of Mao’s proposition, “Study hard and thoroughly understand Marxism.” It is hard to imagine that a worker in a factory filled with the humming of machines and shouts of people would study Engel’s classic work Anti-Dühring whenever time allowed. Let Us Discuss Merits and Crimes, painted by a worker from Yangquan County, also used symbolic means to illustrate how Lin Biao and other capitalist roaders adopted Confucian thought and condemned Qin Emperor’s burning of books in order to criticize the proletariat class. How deeply did the common people really understand the struggle between Confucianism and the law? Peasants still reminisce about the story of “Confucius Killing Shao Zhengmao” broadcasted on loudspeaker in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution. They were not interested in the historical story—simply infuriated that Confucius looked down upon peasants. After studying Mao’s words, “The people are the creators of history” and “The countryside is a vast area where great things can be done,” the peasants and workers were determined to condemn Confucius for looking down upon laborers.

Through art, the peasants and workers eagerly supported national policies. They were highly regarded as the master of the nation, and their work was widely recognized by publishing houses, art associations, and professional artists. Some artists even denied their past experiences and knowledge to embrace and study the collective nature of art. During the Great Leap Forward Peasant Mural Movement, most of the murals created were happy reflections of the People’s Communes. In reality, many peasants revolted and held contempt for national policies, proven by the many instances of slacking off during work, cutting down output, stealing, hiding partial harvest for private use, or fixing farm output quotas for each household. Peasants had their own way of dealing with such behavior, while academic Li Huaiyin in Village China under Socialism and Reform analyzed the “resistance of justice” and “weapons of the weak” that were supposedly based on a pre-existing value system and shared knowledge. The People’s paintings were not only propaganda tools; they also served as the People’s means to express dissatisfaction and frustration. In Pi County, the first farmer’s painting, Old Niu’s Accusations, described a commune member’s criticism of a cow feeder’s unreasonable deductions of cow food. In Yangquan, a worker’s painting of “Revolutionary Production Must Increase, Leading Cadres Must Fall” depicted idle factory leaders in an office, neglecting the behavior of the People. These works about collective property, farm cows, and criticism of officers were allegedly highly regarded by Party officials. The Party encouraged criticism as a supportive tool of political propaganda and administrative power. Workers and peasants who participated in artistic creation were not only grateful to participate in the mobilization of thought, many practiced art for other reasons—to understand information, to seek promotion, to learn a handcraft, to secure a more relaxed role of labor, to change the influences of a poor family background. Many a worker and peasant artist changed their fate through art, finding themselves closer to the center of power and opportunity and raising their social status.

Today, many academics reject classic case studies of “peasants and workers painting peasants and workers;” they consider such artworks as visualized political slogans. Others praise this art as a new socialist culture that was not only an expression of the peasants and farmers, but also a historical subjectivity in itself, created by the People. Perhaps, in truth, the situation is not so absolute. Political power that proclaims itself to be based on the alliance of peasants and workers must establish the peasants and workers as the core of society, the main voice of the People. The nation needs to establish their leadership in the realms of culture and ideology. Indeed, the peasants and workers produced a distinct visual language—yet their role as the central voice of society was established only on a formal and symbolic level. These masters of the nation, who presumably practiced the right of speech, were elevated to a respectful social and political status that they had never experienced before. In the national operation of cultural propaganda, the People also received many benefits—yet their political rights as individuals remained vague and nondescript. In the context of highly promoted slogans, it is difficult for the People to act upon their hidden instincts to revolt.

These are our thoughts regarding grassroots art during this period