AS SEEN HERE: VIEWS OF CHINESE CONTEMPORARY ART IN THE U.S.

| March 26, 2014 | Post In 2014年2月号

1999, performance, Seattle Asian Art Museum

FROM AT LEAST the time of Nixon’s visit in 1972, the United States has had a love-hate relationship with China. Opening relations with the People’s Republic did not stop Americans from calling it “Red China,” nor did it change their love for fortune cookies. This attitude—a combination of political paranoia, economic competitiveness and cultural nostalgia—spilled over into the art world and influenced its views of Chinese contemporary art. Since the mid-1990s, when Chinese artists first gained attention in the U.S., American art lovers have looked at their creations through yellow-tinted glasses, unable to separate appreciation of the art from often-conflicting sentiments about Mainland China.

For most New Yorkers, Chinese contemporary art reached their consciousness with the exhibition, “Inside Out: New Chinese Art,” which was shown at Asia Society and PS1 in 1997. Most of the coverage at the time was positive, highlighting the show as a breakthrough in introducing important new names to the global art dialogue. The main thrust of most of the reviews, however, was the collision of East-West aesthetics perceived in the works of such artists as Cai Guo-Qiang and Xu Bing. These two artists were already living in New York at the time and were deeply imbued with Western conceptual strategies. But it was not their familiarity that garnered accolades. It was their exoticism. Both artists wisely employed Chinese elements in their installations, making their work as effective in conveying exploration and discovery as postcards from the Great Wall.

Lois & Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art

In many ways, Chinese painters who stayed home, such as Zhang Xiaogang and Wang Guangyi, were the easiest for Americans to understand. Painting in an exacting manner that seemed like a flashback to the days before Abstract Expressionism, Zhang captured audience attention with his pensive portraits of families in Mao suits, interpreted as a criticism of the Cultural Revolution by Americans who had barely gotten past this impression of the PRC. Likewise, Wang (with his Mao meets Warhol compositions) gave Westerners the sense of an avant-garde ready to critique Chinese society—very congruent with the Western tradition of artist as liberator. These two artists, whose work represented neither aesthetic innovation nor a view of China conflicting with American political outlook, were quickly integrated into the market, albeit at much lower prices than they fetch today. If I had had USD 25,000 then—the asking price for a Zhang Xiaogang in 1997—I’d be a millionaire today. Still, many at the time thought it was crazy to spend even that kind of money for a relatively unknown Chinese artist with an unpronounceable name.

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, 2012

From left: Beijing’s 2008 Olympic Stadium, 2005-08; Divina Proportione,

2006; F-Size, 2011

Performance artist Zhang Huan was the one artist in “Inside Out” who explicitly benefited from the show. Having come to the United States specifically to participate, he wowed crowds with his work Pilgrimage— Wind and Water in New York, in which he laid on a block of ice encased in a Qing-style bed, surrounded by barking dogs. Meanwhile, his photograph To Raise the Water Level was featured on the cover of the exhibition catalogue, and thus became emblematic of the show. Roberta Smith in The New York Times then described the artist as follows: “Mr. Zhang enlivens established Conceptual conventions with a sense of Chinese history, character and art and his own understated stage presence.” He soon was performing across the U.S. and Europe, boasting a succession of shows at Deitch Projects, Max Protetch, and Luhring Augustine, all in New York.

Almost as soon as these artists were introduced to New York, a backlash set in, casting doubts on the notion that a new art movement could arise in a country perceived to be as repressive as China. The criticism—little of which made it into print, though it often cropped up at exhibition openings and cocktail parties—fell into two camps, both predicting that the fashion for Chinese contemporary art would be short-lived. On the one hand, many compared the rise of this interest to the craze for Russian art in the 1980s, linked to the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In that fad, many looked to Russian artists as a key to the supposed liberalization that some predicted would occur, and expressed this optimism with their checkbooks. When these false hopes failed to materialize and Russian artists did not live up to these high expectations, the market for their work collapsed and the majority of them disappeared from the American scene. Likewise, some said, the boost in Chinese contemporary art was bolstered mainly by political aspirations, and would certainly deflate as China showed its true colors.

Installation view, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, 2012

Collection of the artist

PHOTO: Cathy Carver

The other criticism was that this was just a market phenomenon isolated from the genuine support of museums and the critical community. This is a criticism that Chinese contemporary art has not been able to shake, even as the market continues to grow. Every year since 1997, I have been asked if this is a “bubble” as prices for works by a single artist have risen from USD 25,000 all the way up to USD 10 million. As one young Chinese artist once told me, “Yes, this is a bubble, but it’s made of steel. It is the strongest bubble.” The notion that there are no Chinese museums validating Chinese contemporary art and little museum interest in the States is rooted in a situation that was more or less true in the early 2000s, but has changed significantly with time. I have had American art critics pointedly question me about the lack of Chinese critical theory and art criticism, smugly certain that their views are valid despite the fact that they cannot read Chinese, nor have they tried to read the translated critical literature in the field.

Both of these criticisms were directly challenged by two events: Cai Guo-Qiang winning the Golden Lion at the 1999 Venice Biennale and Hou Hanru bringing the art world to China with the Shanghai Biennale in 2000. Cai Guo-Qiang’s installation, Venice’s Rent Collector’s Courtyard, was a re-creation of the well-known Cultural Revolution-era statuary (a fact that did not please the original sculptors). Cai’s great innovation was twofold. One, he had the work fabricated in public during la Biennale. Secondly, his was a conflation of past and present, as these statues, rife with Chinese history, were rendered in Western realistic techniques. It helped that he was not the only Chinese artist in Venice that year; artistic director Harald Szeemann included more than a dozen Chinese artists in the main exhibition, and Paris-based artist Huang Yong Ping represented France in the French pavilion.

Hou Hanru, commissioner of the French pavilion at Venice in 1999, made his mark the next year with his Shanghai Biennale, the first to include international artists on par with contemporary Chinese artists. When first told about the Shanghai Biennale, I distinctly recall several of my fellow New Yorkers laughing at the pairing of the two words, “Isn’t that an oxymoron?” They were confidently certain that no such thing could take place in a politically backward place like China. But Hou proved them wrong, inviting dozens of art aficionados and curators to come to Shanghai and see for themselves.

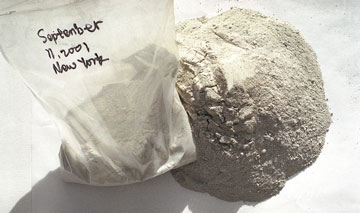

used dust that he collected from the streets of lower Manhattan in the aftermath of September 11 to attempt to understand the gravity and implications of the event.

These two exhibitions refuted the notion that Chinese contemporary art could only thrive in the marketplace. Chinese artists were now obviously performing well on the biennial circuit. Around this time, however, leading New York critic Peter Schjeldahl dismissed biennials en masse as “festivalism” encouraging the development of artworks as merely spectacles and crowd-pleasers. This criticism thereby put Chinese artists in a bind. They were damned if they succeeded in the art market, and equally at fault if their work garnered attention in museums and biennials throughout the world.

These criticisms—especially that of festivalism—have also stuck with Chinese artists to this day. In fact, when Cai Guo-Qiang had his retrospective at the Guggenheim in 2008, The New York Times dismissed the show as a display of special effects, spectacular but meaningless. When Lin Tianmiao was given a retrospective at Asia Society in 2012, a leading critic compared her installations to department store window dressing. And when an artist varies his strategies from biennials to gallery exhibitions, as Zhang Huan has done, he is often criticized as “selling out.”

In recent years, however, Chinese artists have made progress towards being recognized as individual artists, rather than ambassadors from a foreign country. It has helped that most major New York galleries have taken on at least one Chinese artist: Yang Fudong at Marian Goodman; Liu Xiaodong and Ai Weiwei at Mary Boone; Liu Wei at Lehmann Maupin; Xu Zhen at James Cohan; Zhang Xiaogang, Zhang Huan, Li Songsong, and Song Dong at Pace; Huang Yong Ping at Barbara Gladstone; Lin Tianmiao at Galerie Lelong; and Yan Pei Ming at David Zwirner. All of these artists have had solo shows in recent years, some to critical acclaim even as jaded on-lookers still stood by insisting that all this will soon past.

None of these artists have risen to the visibility accorded to Ai Weiwei, who has captured broad appeal in the United States as much as a dissident as an artist. He has achieved a great deal, including a solo traveling museum show that originated at the prestigious Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. in 2012. Soon to make its way to the Brooklyn Museum, this is the widest seen and most extensive exhibition of a Chinese contemporary artist to ever be held in the U.S. It gives viewers a full overview of the artist’s prodigious output, from his early experiments with Han vases to his latest installations based on debris found in the aftermath of the Sichuan earthquake.

It made great sense to include in this survey those works which are pointedly political and verge on the documentary, from Ai Weiwei’s photographs of his time in New York in the 1980s to the list of names of children killed during the Sichuan earthquake. But, this material— also included are his images of the Bird’s Nest under construction—have confused some critics who view them as a kind of activism, separated from art-making. While every review conceded that Ai Weiwei is a great man, several countered that he was merely a so-so artist. In a recent review in The New Republic, art critic Jed Perl described Ai Weiwei as a “wonderful dissident, terrible artist,” and his artworks as “bone-chillingly cold, the thoughts or attitudes of a great political dissident who remains untouched by even a spark of the imaginative fire.”

It is not surprising that a critic as politically conservative as Jed Perl cannot embrace the notion that Ai Weiwei’s blog posts, videos, rock album, and political activism are all part of an art production that blurs the difference between art and life, personal and public, discrete objects and transactional aesthetics. Yet, even when American critics embrace the scope of Ai’s art practice, they question whether his power is chiefly derived from his political stance. I would say this is an honest question for most people viewing the Ai Weiwei retrospective, not because the artworks are unconvincing on their own, but because we, as Americans, are completely fascinated with the idea of a democracy movement arising in China led by some dissident-artist struggling for freedom. Our criticism of China’s human rights violations dovetail with a Western belief in the radical artist whose words or works can change his society. Ai’s actions over the past decade fit perfectly into that scenario, but that shouldn’t overshadow his achievements as an artist. Ironically, his own criticisms of China and Chinese artists have lead some to believe that it is impossible for China to produce a great artist, even if that artist is Ai Weiwei.

The challenge for all artists, no matter what country they come from, is to be recognized on their own terms as an individual, despite cultural differences. Such differences play less and less a role in Chinese artists’ output as China has become more global and younger Chinese artists explore personal issues instead of national ones. However, even as the notion of “Chineseness” recedes in Chinese contemporary art, Chinese artists may still find that critics abroad insist on imposing it on them. It is not the role of Chinese artists to change American stereotypes about China. Nonetheless, I am finding that as more and more Chinese artists learn to express themselves as individuals, American stereotypes seem more and more irrelevant.