HU QINGTAI PROJECT: BROTHER/LI GANG/LI LIAO/JIANG BO/YANG JIAN/YANG XINGUANG/ ZENG HONG/ZHAN RUI

| March 26, 2014 | Post In 2014年2月号

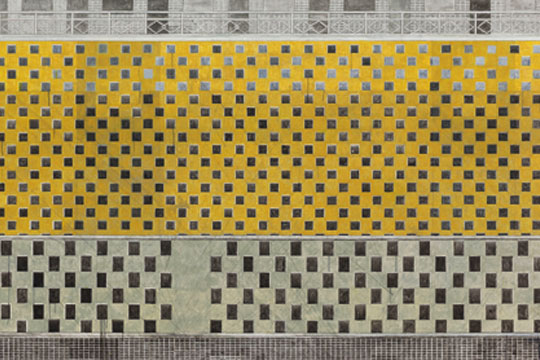

One of Zeng Hong’s Projects,

2013

Acrylic on canvas, 273 x 160 cm

For his newest project, Hu Qingtai purchased and executed several plans for artworks. The result is an exhibition of eight works, each made according to the ideas of a different artist. The artists are Hu’s older brother Hu Qingyan, Li Gang, Li Liao, Jiang Bo, Yang Jian, Yang Xinguang, Zeng Hong, and Zhan Rui. By “depriving” the other artists of their production and authorship rights, Hu goes beyond the roles of collector, curator, or agent. “Purchasing” as a method of acquisition becomes more akin to “buyout” than to collecting, whereas “executing” the plans dissolves the originality of the artworks.

As an artist, Hu Qingtai does not depend on any specific medium for his practice, which is instead defined by linguistic and textual narrative. In addition to the plans and completed works, Hu also displays the contracts he signed with the artists. In the agreement with Yang Jian, the purchase procedure is outlined thusly: “Yang Jian requires that payment for the yield of his scavenging over the past two months cannot be made in cash (renminbi). Payment method shall be as follows: From July 1, 2012 to September 1, 2012 inclusive, Hu shall assist Yang Jian with household chores, and serve as Yang’s driver when needed.” What is ultimately shown in the exhibition are four paintings that Yang Jian had found in the trash near his studio in Heiqiao, probably thrown out in the aftermath of the infamous rainstorm of summer 2012. The plan contributed by Li Liao is a video performance that records the receding silhouette of a figure on a highway as it disappears beyond the horizon line. In contrast to this solitude, the purchase agreement proposed by Li is both sentimental and nonsensical, requiring Hu “to keep in touch with Li Liao and form a lifelong friendship from this day on.”

Meanwhile, painting, that most widely circulated and traded kind of art, represents the only medium on show that was not acquired inkind. For Zhan Rui’s project plan, Hu paid 500 yuan. The result is a painting by Hu Qingtai “in the style of Zhan Rui.” In Zeng Hong’s case, Hu acquired the description and authorship rights of a painting for 20% of its sale proceeds. The result is another Hu painting, in the style of Zeng Hong.

Putting aside the novelty of a solo exhibition that consists of works conceived by other artists, the most interesting and thought-provoking aspect of the “Hu Qingtai Project” is its structure, which Hu has set up as a way to spur discussion of the unwritten rules and roles in the art world. In a game of simulation where he interprets the roles of artist, curator, agent, and collector, Hu followed the conventional process of first reaching verbal agreements with an artist, and then writing down the terms by hand and signing the contract. Hu also included annotations of the reasons behind his choices: “Because I like him as a person, I also like his art”; “I have a good feeling about him”; “He readily agreed.” These apparently off-handed comments seem to be part of a serious joke that Hu is making. The eight hastily written contracts—corrections and amendments and all—are framed and displayed in a corner of the gallery, providing more than just expansive explanations and reading material.

Of the myriad possible ways to examine the art world, the angle of entry of this project is not new. There are several contemporary artists and art collectives who have carried out similar investigations: MadeIn Company, Hu Xiangqian, Gland, and the recent WeChat auction group set up by Double Fly, among others. In short, the artist has already emerged to play a hybrid role in the chain of art production, embodying multiple identities between which he switches with ease. In comparison, Hu Qingtai’s practice seems like the beginning of a rather twisted game. His suggestion that the artist has signed himself into nothing more than project executor—that individual creative power has been dissolved—is certainly representative of the reality behind certain aspects of art production.