A FORM NO LONGER RADICAL

| September 11, 2014 | Post In LEAP 28

By today’s standards, Musique Concrète seems like idealist fundamentalism, attempting as it does to provide a morphology and paradigm for sound art. Yet can this paradigm once again initiate revolution?

Though war has been, is now, and will always be a catastrophe for art and culture globally, in the wake of the flames of the Second World War new kinds of recording technology came into being that, out of the void, opened the door to an unanticipated realm of musical experimentation. This was the birth of a long-evolving movement by the name of Musique Concrète. At its start, Musique Concrète boldly deserted the mainstream sonic system of the time—based on Schoenberg’s 12-tone practice—and introduced the possibility of a new kind of freedom in the typomorphology of sound. Musique Concrète pursued, through editing and reconstruction, the painterly compilation and collage of that abstract and intangible substance we call sound, turning it into a readable, moldable material. The proposition behind this philosophy and style of working would go on to have a profound impact on the future of electronic music, radio, television, and cinematic composition. With this backstory in mind, the international exhibition “Around the Sounds” recalls different forms of Musique Concrète over the years, extracting a cross-section of the history of French sound art.

In his speech at the opening, curator James Giroudon reaffirmed the importance of Musique Concrète to the history of sound art and delved into its shared context with the sound art tradition. In his curatorial essay, he maintains that, in our reflections upon twentieth-century music, we ought to consider the notion of space. Visual art’s infiltration into the world of sound has made it impossible for artists to ignore the shift between the sensory experiences of different forms of artistic expression. Though Pierre Schaeffer, founder of Musique Concrète, believed that space was not a visual entity, Giroudon hopes that, by harnessing the enveloping, fluidic nature of sound, a new sonic and visual landscape might be built “around sound,” towards the creation of a more expansive dimension of time and space.

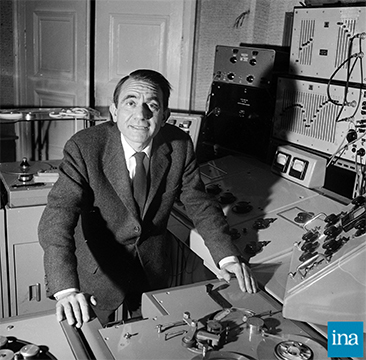

A section of the exhibition devoted to Schaeffer features Three Documents from the Archives of the INA (Institut national de l’audiovisuel), which takes a look back at the birth of Musique Concrète. Schaeffer’s Railroad Study (1948), from his early days experimenting in the studio, is an endless loop of recorded samples of railway noise and musical instruments, the result of which is a very eerie aural experience. William Anastasi’s Coleslaw (2003) follows a similar logic, projected on loop from a monitor on the floor. Anastasi superimposes film recordings of himself singing and playing Cole Porter songs as if he were tossing and mixing coleslaw, in what seems like a tribute to Schaeffer. As far as Schaeffer was concerned, however, Musique Concrète meant cutting down on sensory stimuli as much as possible, especially the visual. In his Treatise on Musical Objects, Schaeffer writes of “a mode of hearing in which sound is at the very center of the hearing experience, separated from its original source and meaning.” Schaeffer’s most important collaborator, Pierre Henry, opposed this sensory centralization, holding that the experience of sound was, by necessity, a cross-sensory one.

Perception of visual space is subject to the eye’s appraisal of distance; in any one space—say, a certain building—the reception and feedback of sound can provide a viewer with a fuller and more reliable understanding of its dimension and structure. Zoe Benoit’s Archisony series hails from a generation of younger artists whose practices often engage with this phenomenological reality. Benoit, the exhibition’s youngest participating female artist, deals with the movement of sound through space. Audience members listen through headphones to field recordings (including her own spoken dictations) made by the artist during her travels through varied environments. Wind Break and In Tumult as in Silence—abstract, poetic names—end up calling forth very specific imagery: associations perhaps to the works of a number of New Wave directors (Musique Concrète happens to have influenced many auteur films). One title, So, Still in the Corbu?, is an obvious reference to Le Corbusier’s influence on architecture, while Baguettes (with several pieces of lumber lined up against a wall) and Paraboles (made in copper) combine freely in the imagination into a band of primitive percussion instruments.

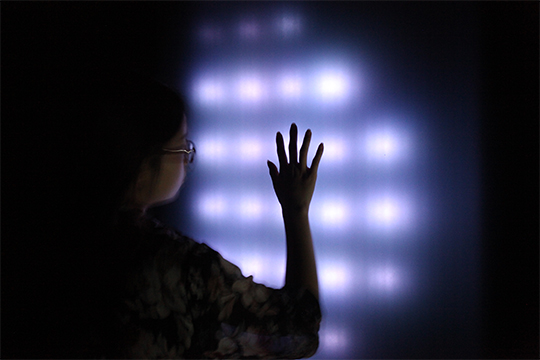

About two years’ time has passed from the birth of idea behind the exhibition and the preparations required to its ultimate realization. The A4 Contemporary Arts Center in Chengdu has completely transformed its space to accommodate the works’ varying requirements of their environments and impacts on audiences. Most noteworthy in this regard is Denys Vinzant’s In This Moment (2000-2013), a piece that places nearly impossibly high demands on the interaction between space and sound. The installation is comprised of 74 glass plates, in a display of a more delicate side to the artist’s oeuvre. Every single piece of glass is a small speaker; the artist uses glass of differing dimensions to produce changes in pitch and a timbre that rings crisply throughout the space. Every piece of Vinzant’s music is scored in golden ink on sheets of glass, giving it the ritualistic air of an ancient musical note mandala. Vinzant reserves a part for vocals in this movement, the epitome of sound materialized.

The “Around the Sounds” project comes out of the Lyon-based sound research institution Grame (Grame centre national de création musicale). Members of this loosely assembled team come and go freely with the beginnings and ends of their projects. Musicians and technicians work together to complete the works, musicians writing scores or communicating concepts and technicians realizing visions. As abstract visual extensions of sound, the installations’ abiility to depict or represent becomes very important. Chinese viewers expect, at the very least, a pleasing proportion of interactivity, sound, and light. But works of the Musique Concrète tradition are not there to delight audiences; some even explicitly aggravate them, such as Grame co-founder Pierre Alain Jaffreno’s Musica Mobile (2001). In this work, the analog track of a rapid piano performance is laid over itself eight times (similar to the effect that eight Philip Glass songs played simultaneously might have). All this aside, most of these works still meet audience expectations. Sound has become a sort of device, a negotiation of input and output at the level of physics.

By today’s standards, Musique Concrète begins to seem like idealist fundamentalism, attempting to provide a particular morphology or paradigm for sound art. Whether this paradigm can once again initiate revolution, or revive a performance whose relevance may be fading today, is a question worth exploring.