THE SPACE TRAP

| September 5, 2014 | Post In LEAP 28

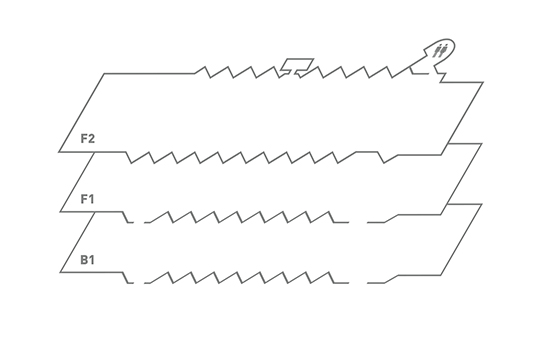

Central Gallery, 8.5 m high, area of 800 square meters

Collection Gallery, 6.8 m high, area of 600 square meters

Chinese Gallery, 6.5 m high, area of 270 square meters

Suspension Gallery, 5 m high, area of 100 square meters

In addition, there is a basement gallery, a second floor gallery, a hallway measuring 17 m long x 3 m wide x 4.5 m high, and two folding passages flanking the Central Gallery, which are 3 m wide at their narrowest and at their widest measure 7 m wide x 6.8 m high x 53 m long.

THE PRIVATE ART museums appearing on the outskirts of Chinese cities in recent years are like vast fairy tale castles flung down from the sky—they bear no relation to their surroundings. Forging the ambitious myth of art in the wilderness, after all, is a great way to catch our attention. It is actually quite fitting to mount a large-scale exhibition titled Tales from the Taiping Era at the Red Brick Contemporary Art Museum in a distant suburb: as evening falls and few taxis pass by, the small number of black cabs are quickly filled. The art tribe stands at the side of the road waiting to catch a ride, folding their arms in boredom and muttering under their breaths about being “out in the sticks.”

I’m slowly getting used to going to contemporary art exhibitions “out in the sticks,” on the edges of the city, both because it’s easier to follow the wishes of the patron in building an exhibition space—no one wants to have to contend with planning committees in the creative districts, with the endless hassle of converting old factories to exhibition spaces—and because, in recent years, people have become very clear about what kind of space contemporary art should be displayed in. Ten or more years ago the theme of an exhibition could dictate the content of the artwork; now the structure of the exhibition space has gradually assumed an influential role in the production chain of contemporary art. Through clever spatial design and generous funding, it is entirely possible to manipulate artists to produce the works the patron prefers. The gallery has long been more than just the medium for disseminating contemporary art; it is a tool of production. Generally speaking, a curator can determine the tone of an exhibition and its list of artists, but when it comes to producing work there is not much room to negotiate with artists. One might say that the curating profession in China is in an embarrassing position, where it is almost impossible for curators to exert any positive or substantial influence over the final forms of artworks.

In the exhibition galleries of the Red Brick Contemporary Art Museum, the flow of the exhibition space is free and there is an open field of view, making it well-suited to showing large installations, multi-screen video installations, and series of paintings. As far as established Chinese artists are concerned, provided with this kind of space they will effectively transform each gallery into a stage for their own individual performance. Moreover, the more familiar the artistic language, the easier it is to draw viewers’ attention to evaluate an individual artwork, while the diversity of artists making up the exhibition and the contradictions between them are ignored. In this way, the design of the space hampers both dialogue between works and any controversy they could produce. What we are viewing is, in reality, a group of individual shows, not a group show—the exhibition’s point of view is weak and unclear, and the impact of its curatorial work is spread thin over a large area. If curators cannot exercise their wills over this flawed space with a clearly ordered flow and floor space, roles will automatically be assigned as directed by commission and construction and the resulting exhibition will have a clear standard of judgment and a strict hierarchy: several main galleries are given over to famous artists, and some apparently inferior galleries to those who are less well established, or to more unconventional cultural activities, to fill space.

Most people’s understanding of contemporary art begins with a white cube gallery space, and with experience in viewing art they gradually form a clear standard for the quality of artwork, which also gradually limits the imagination for contemporary art. Being out in the sticks offers the convenience of planning and building independently, which can stimulate innovative practice and make it easier to set clear goals: a joyful, well-received exhibition full of good artwork. Does this state of affairs strengthen the contractual relationship of production between patron, curator, and artist? Or is it a relationship of artistic creativity?

The exhibition is titled after the Extensive Records of the Taiping Era in order to evoke the heterodox spirit of this large collection of popular folk stories of ghosts and anomalies, and to emphasize the narrative and fictional properties of the exhibition and its individual artworks, as if to stand against the empty language and formal stultification of many exhibitions. I expect this was by no means the curators’ only motivation, since it does not appear to be the result of a thorough analysis of the creative difficulties of art; in fact it applies equally to a large number of exhibitions. Starting from this recognition of the problem, how might the curators begin a meaningful discussion with artists who have been on the front line of creative work for decades? Given that there is no possibility for dialogue, how can they attract so many well-known artists to participate in the exhibition? And why are these artists willing to show their work under the title Tales from the Taiping Era?

Curating an exhibition in a new environment involves different responsibilities and areas of work to focus on. If the gallery space is not conducive to promoting dialogue between artists but instead spurs them to produce great works that emphasize the individual artists’ brands, the exhibition becomes an activity reorganized only by patrons and artists—but at least it is not a working relationship between intermediaries and producers. I do not mean to imply that the design of galleries should become the driving force behind the production of contemporary art, but rather wish to explain that the many unresolved issues in the art market are becoming both more acute and more covert in purpose-built exhibition spaces. It is becoming more of a challenge for curators and for art to break out of the current predicament.

Patrons, curators, and artists involved in the art world are problematic and even hypocritical individuals. One good exhibition or artwork cannot resolve their problems; only adjustments to the processes of investment and administrative support, curating and production of art, and forging of cooperative relationships can give rise to previously unimagined possibilities.