ISA GENZKEN: RECEIVERS

| February 25, 2015 | Post In LEAP 30

TRANSLATION / Xia Sheng

Art historian Hal Foster’s extended review of German artist Isa Genzken’s MoMA exhibition in the February 2014 issue of Artforum begins with the statement that Genzken’s career has been wrongly contextualized by her relationships with more famous male artists. While this is probably true, Foster proceeds to draw an almost entirely male art historical lineage for Genzken’s work. In doing this, Foster references 35 male artists and writers, mentioning only one other woman.(1)

I mention this because Foster, like so many curators and art writers, superficially points to a social issue—gender disparity—and simultaneously upholds the ideological structures that perpetuate the issue, seemingly without much cognitive dissonance. It is within the very architecture of our speech, comportment, and social relationships, we have learned, that signifiers of authority, class, race, and gender are frustratingly concretized and coded. Luckily, Genzken is an artist whose work deflates such binary distinctions.

Her work generates confounding hybridities that collapse dichotomies such as male/female, outside/inside, architecture/sculpture, high/low, new/old. Take for example, her early work “Ellipsoids” (1976-82) and “Hyperbolos” (1979-83), computer-designed sculptures installed on the floor that resemble garish, gigantic needles and can be read as a middle finger to Minimalism. While Genzken channels Minimalist forms and practices, she upstages their industrial production by introducing the sphere of the technological, collaborating with a computer programmer to create otherworldly elongated forms. In rooms full of work by Richard Serra, Carl Andre, and Sol Lewitt, her bright yellow and orange oversized knitting needles stand out as a gaudy riposte to composed, spectator-conscious Minimalism.

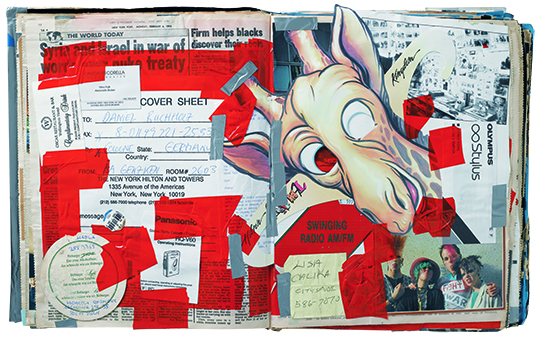

In her series “Fuck the Bauhaus (New Buildings for New York)” (2000) and “New Buildings for Berlin” (2001-2006), Genzken creates kitschy, slapdash architectural models out of cheap found materials that are installed on hollow rectangular plywood plinths resembling cabinets or windows. The buildings depicted by the architectural models reference real Miesian geometries but are simultaneously nothing short of disastrous—one model, for example, is made out of a pizza box and festooned with fake flowers and neon orange plastic construction netting.

Another, a block made out of construction-barrel orange acrylic glass topped with a neon rainbow Slinky, is also strewn with consumer detritus, suggesting that the cityscape might reflect the more vulgar happenings of the urban condition. The title “Fuck the Bauhaus” insinuates that Genzken really doesn’t like the Bauhaus and its associated Modernist masters—founder Walter Gropius, architect and designer Marcel Breuer (who designed the iconic Whitney Museum of American Art in New York), artist László Moholy-Nagy, and architect Mies van der Rohe. As with “Ellipsoids” (1976-82) and “Hyperbolos” (1979-83), Genzken again appropriates the formal characteristics of her canonized male precedents and introduces them to their gaudy, popcolored, consumerist antithesis.

The concepts of architecture, space, and ruins come up frequently in Isa Genzken’s practice. This is not terribly surprising, as Genzken has lived in postwar Germany, rife with rubble, most of her life, spare frequent stints in New York. Genzken is rumored to love the humbling scale and theatricality of Manhattan. Her 2008 exhibition “Ground Zero,” at Hauser and Wirth in London, featured architectural proposals for the area surrounding the World Trade Center. Again, these architectural proposals could be more accurately considered sculpture grounded in architectural thinking. Rejected are the tempered glass and stainless steel corporate monstrosities that have taken over Lower Manhattan; rather, Genzken channels the banal community usage of these sites. Car Park (Ground Zero) (2008) stacks what appear to be several plastic fan covers into a vertical car park, while Hospital (Ground Zero) (2008) places a makeshift vase of artificial flowers atop a column covered in mirror foil and lime green fabric, itself on top of a drink cart riding on casters. Memorial Tower (Ground Zero) (2008) fuses stacks of clear plastic storage boxes bound by tape and marked by dripped silver paint, as if the steel structure were bleeding. A cipher for the human body, 35 mm camera film affixed to the side of the metaphorical building spills down its side. This gesture brings to mind the photograph Falling Man, by Richard Drew, which depicts a man falling head first, almost calmly, to certain death against the background of the World Trade Center. Perched atop Genzken’s mock building are two rolled-up pieces of red acrylic paper referencing both the North Tower’s spire and the space between the Twin Towers. This could also be read as a space separating two entities—the building and the body, the self and the stranger, life and death.

Genzken’s earlier work also bears this elegiac quality. Fenster (Window) (1990) is a rectangular concrete window that recalls East Berlin’s socialist plattenbau housing. But, taken separately and placed on a plinth, the window possesses an incredible lightness in spite of its mass, conjuring thoughts of luminosity and permeability. This formal dichotomy frequently works its way into work about architecture. Genzken often works through the transversal of antithetical forms: the corporal and the architectural (always in sync, never as one), the mechanical and natural. Simultaneous interiority and exteriority—private and public—is inherent to being human as well as the nature of architecture.

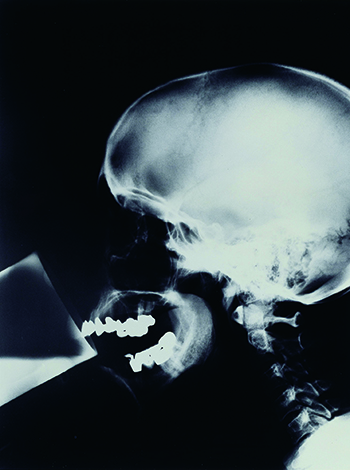

Perhaps Genzken’s most beguiling and confounding work touches on reception devices: the ear, the stereo. Her outdoor project Ohr (Ear) (2002) adorns the Innsbruck city hall with a gargantuan print of an ear, as if the building were listening in on the town’s conversations. But the ear is so large that it also prompts us to reflect on the nature of the organ, and to ponder why the artist would choose an ear, rather than an eye or mouth, to decorate the building. The ear is the only orifice on the human body that is permanently open on both sexes, making it, along with our sense of touch, one of the primary senses through which we experience the world. For Weltemfänger (World Receiver) (1987-89), made just before Fenster, Genzken recreates stereo receivers out of concrete and metal radio antennas—a solemn reflection on silence and agency.

When Genzken’s work isn’t elegiac or straight-up antagonistic, it bears a unique quality rarely glimpsed in contemporary art: it’s fun. It’s covered in dripped paint, mirror foil, fake flowers, and Slinky toys. It’s fun in a way that makes Bauhaus look boring. Her work brings to mind the oft-quoted Emma Goldman: “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution.” While Genzken has long had to dance in a field dominated by men, she proves that revolution is best served with a groove.

“Isa Genzken: Retrospective” is on view at the Dallas Museum of Art September 14 – January 4, 2015 as the last leg of the traveling exhibition previously shown at Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, and Museum of Modern Art, New York. Lastly, “Isa Genzken. Neue Werke” is on view at Museum der Moderne Salzburg November 22, 2014 – February 22, 2015, and will travel to Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

(1)Male figures referenced: Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, Gerhard Richter, Wolfgang Tillmans, Kai Althoff, “her paternal grandfather, the Nazi” (Karl Genzken), Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Blinky Palermo, Barnett Newman, Sigmar Polke, Herbert Bayer, Mies van der Rohe, Richard Hamilton, Leonardo da Vinci, László Moholy-Nagy, the Bauhaus, Albrecht Dürer, Cabaret Voltaire, Marcel Janco, Hugo Ball, Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire, Lawrence Weiner, Leonardo DiCaprio, Sigmund Freud, Jacques Lacan, Martin Kippenberger, Mike Kelley, Marcel Duchamp, Jeff Koons, Takashi Murakami, Kurt Schwitters, Robert Rauschenberg, Edward Kienholz, Joseph Beuys, Dieter Roth. Female figures mentioned: Rachel Harrison.