REEDUCATION: A SECOND BEGINNING

| February 25, 2015 | Post In LEAP 30

TEXT / Shi Qing(1)

TRANSLATION / Katy Pinke

EDUCATION IS AN ancient profession. In China, the arts academy has a long history, dating back centuries. Since the dawn of the modern era, it has been the foundation on which the broader system for the training and cultivation of artists has been built.

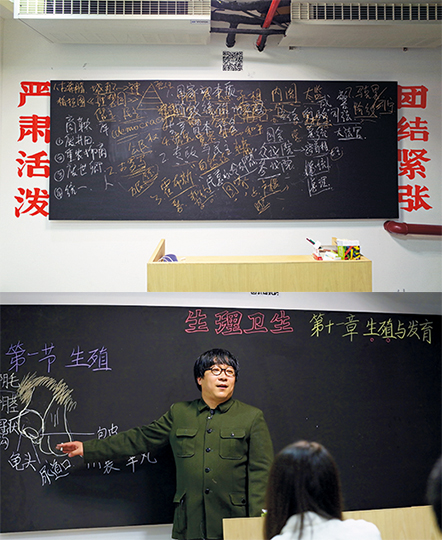

Reeducation is a term appropriated here for the sake of convenience. We define it as the process of self-education that takes place after formal institutional education has come to a close and a student enters into society. It is the beginning of a phase in which an artist has more independence and maturity, lasting two to three years or longer. Contemporary art became a part of the official school system just over ten years ago, but this system had no clear way of incorporating this new branch—more like a bramble—into its structure. Some instructors from the traditional system switched over to contemporary art, but, more often, this new area of study was led by practicing contemporary artists, art critics, and curators serving full-time, substituting sporadically, or coming in occasionally to lecture. Contemporary art was taken in as a sort of foreign object, awkwardly implanted into the original rigid block that was traditional art education. Wanting results and incongruences have inevitably arisen.

For students of traditional art, there exists a stable, accepting environment and clear channels to employment. Of course, one still crosses a boundary in going from education to employment; the former does not lead seamlessly into the latter. But, in contemporary art education, those who teach predominantly wear two hats: that of practicing artist and that of educator. As for students, many have the opportunity to see exhibitions and even participate in them during their time at school. In the age of the internet, there is about as much sharing of artistic information as there are artists, and the contemporary art educational experience varies from teacher to teacher. There is no fixed model, but there is one shared fundamental principle: learn by doing. It is a principle followed to the extent that the line between the study and practice of contemporary art is blurred, the two seemingly converging in a continuous flow. They do, however, possess distinct differences.

Education Continued as Practice

A mentor’s guidance is always necessary, even in studying the most obscure facets of Zen Buddhism. But, in the process of reeducation, the first thing a student must confront is the loss of the teacher. Art is, after all, a creative practice based on an individual’s personal observations. The disappearance of the teacher is a kind of fracturing or breaking apart as much as it is the beginning of becoming an artist. This loss occurs on a psychological level, but is also reflected on a technical level. It manifests itself in the question of how to take what one has learned in school, deepen it, and reflect upon it. The curriculum for a given course in school runs for one to two months, long enough for students to gain a general understanding of the subject matter but nowhere near long enough for them to truly internalize it.

Artists doing the teaching also have their own difficulties. As teachers, the most important function artists can serve is to inspire their students through their own practices, drawing on their own knowledge, views, value systems, and tastes. On the one hand, direct experiential teaching like this allows students to come more readily into contact with real life experiences; if students aren’t given the opportunity to broaden their horizons in terms of the references to which they’re exposed, their experiences become monotonous. On the other hand, a teaching artist cannot be turned into an encyclopedia—pushed to portray the entire framework of art history and exhausted by the pursuit of demonstrating method after method. After all, the artist is not an educator by vocation; even for a professional educator, it wouldn’t necessarily be possible to answer these sorts of demands. Starting only from knowledge in the absence of practice, courses devolve into vague abstraction.

The ideal of the almighty teacher does not truly exist in nature. Contemporary art itself necessitates a break with authority. The lost teacher is a permanent state of being; within or beyond the art school system, it is a defining characteristic of contemporary art education. There is no correct choice. All sorts of discomfort and confusion have come out of attempts to impose traditional educational frameworks on the study of contemporary art. One might say that reeducation is, in fact a continuation of contemporary art education—an overflow. Reeducation should not be seen as a supplement or review course for the formal phase of education. Instead, it is a clean break. It fits the mission of contemporary art, comprising a portion of its practice.

Methodology amid Complexity and Change

Reeducation is a kind of self-teaching. It does not follow in linear sequence with formal art education; rather, it is an active form of education built on the premise of artistic consciousness. Students of contemporary art must study art history and theory, as well as the current art system and the work of their peers. These demands make self-education burdensome at every turn. Reeducation includes first amassing a cursory understanding of a wide range of things followed immediately by a reduction or simplification; taking in so much, one must make an active choice as to how to proceed. This choice might take the form of a blueprint or a specific project, or it might be an erasure. In the process of reeducation, building and taking away are intertwined—modifying one another, pushing each other forward.

Starting in 2001, following the exhibition “Post-sense, Sensibility, Alien Bodies & Delusion,” my next several projects came out of this kind of choice of direction and self-education. In those days, Qiu Zhijie and many other artists had just recently been exposed to contemporary art. They engaged in practices critical of the exhibition system, proposing new sites and encountering a variety of specific obstacles along the way—obstacles that they came upon through experience alone, by fumbling their way forward through their own practices while engaging in collective discussions. When they came across gaps in their knowledge or skills, they would explore other topics like theater, live performance, and performance art.

Thanks to the internet and globalization, information is in a constant state of multiplication and flux. Compared to the stable subjects and environments of classical and premodern art, the contemporary situation is more complicated, the workload more substantial, and the work of the artist more dependent upon narrow professional specializations. When divisions of labor come into play, the holistic involvement of the artist—as per John Ruskin—is reduced to something more technical. It becomes the final link along an entire chain of production. Along the way, the mission of art has disintegrated. In contemporary art, artists often tirelessly deepen and expand their relationships to particular materials or creative processes, only to find that the work revolves once more around the same technical or conceptual axis.

Critical and market systems encourage and indulge this identifiable style of work, while less stable or linear approaches are pushed aside. There seems to be a kind of tacit understanding between the structural segmentation of formal education and the hardening and typifying of contemporary art. With contemporary art in this state, it is easier for institutions to offer shortcuts: things they can copy mechanically in order to make work that looks like contemporary art, as well as tricks for explaining and interpreting these works. Reeducation is the opposite; to uphold the values of contemporary art one must have in mind a central problem, then research and form a practice and observational approach to match the subject of the work. One must learn to create and learn on the go in dynamic, complex conditions, always keeping a vigilant, critical eye out for anything that threatens to become fixed or rigid. This is the heart of reeducation, and it is something that formal education has difficulty accommodating.

Institutions and Systems

Boris Groys holds that contemporary art is about the manufacturing of art as much as aesthetic consumption. Exhibiting art has become a means of mobilizing and gathering people together. There is publicity involved; the artist’s work bears a political mission. Reeducation, along with gaining knowledge and skill, is about becoming familiar with the ways in which the organizations and systems around art function. Academic education is organized around the unit of the course or studio. This allocation of students does not arise organically; it is preordained by the administration, with the teacher as group leader taking students through to the completion of the curriculum. The resulting experience is a compulsory, unidirectional one, but classmates also learn from and influence one another, sometimes getting more from peers than teachers. As graduation nears, these administratively conceived bodies break apart and the student population is once again allowed to be made up not of classes but of individuals, ready to enter reality as members of society. This is fitting, as the experience of art begins with individual perspective.

In an era so reliant on divisions of labor, the personal practice of the artist provides one last opportunity to penetrate the entire chain of production through the eyes of a single individual. But contemporary art cannot merely be about individual creation. It doubles as both observer and transformer of the art system. This is where self-organization comes in, as a political approach to art. For students who have just graduated and are preparing to go into the field, self-organization holds an even more practical meaning, fulfilling the need to show work. Art organizations typically serve more senior artists, while younger artists unable to obtain recognition can only create a platform for themselves. In addition to supporting each other emotionally through this process, they increase their opportunities to be seen. By self-organizing, aspiring artists can alter the mechanics of the production of art. Lacking the support of art spaces and foundations, Chinese contemporary art of a certain generation relied entirely on artist initiatives. Reeducation, similarly, is a mode of education based in practice, and involves learning to organize. This is the greatest difference between reeducation and academic education.

In 2008, Hangzhou-based artists Shao Yi, Zhang Liaoyuan, and Wang Xiaofeng organized exactly this kind of project: Small Productions. A group of young artists who had not yet had the chance to show at galleries and students who had not yet graduated used the forum as an opportunity to exhibit. The power of the project resided in its decentralized ethos: whoever had the enthusiasm to do so could participate. The process itself was a hands-on course in the practice of organizing. Self-reliance, adaptability, and the capacity to make innovative use of whatever conditions might present themselves are the tenets of reeducation as it applies to basic effective organizational practices.

Experience in the Real World

University education is based on experiences that have already occurred, from systems of thought that have already become scripture to secondhand experiences of a teacher’s practices. This is not to deny the importance of indirect experience; after all, knowledge has always been transmitted and shared in this way. But, as far as artists are concerned, indirect accounts alone are not enough. An artist’s work must produce something different. It must offer new possibilities. These are things that cannot be inferred or repeated.

Before he or she can be born into the identity of an innovator, the artist is first an observer and laborer, soaking in a subject outside of himself. Reeducation is the self-directed study of the lived, real world context, not the dissection of a corpse. At a time when universal discourse attempts to obscure and flatten the intricate heterogeneity inherent to lived experience, artistic experience must be engaged with the world of globalization. University education is similarly edited down by ideology—by a rigid system that casts off sense and sensibility and does away with natural ambiguity. We have no way of confronting the complex, mercurial world outside, no unobstructed portal through which we might make contact. Reeducation is an attempt to rediscover those lost links in the real world chain—to restore life to its myriad vivid, variegated connections. Putting the rational aside, this is about perceptual insight and physical practice. It is about praxis, capturing experience in everyday life and the politics of exhibitions before converting it all into new knowledge.

Projects can be rooted in observation and intervention at a micro-local level, as with Chongqing-based artist Wang Haichuan’s “Tongyuanju Project” or Chengdu-based artists Chen Jianjun and Cao Minghao’s “Kunshan: Under Construction.” These experiences are always specific and grounded in everyday reality. Though these features themselves cannot be equated to art, they can serve as openings from which to draw out an artistic practice. The process of acquiring hands-on local experience can help to clarify and distinguish the boundaries between experience and knowledge, making us vigilant against becoming fixed in a particular way of thinking. Those who experience something firsthand often find it easier to dispense knowledge and advice with certainty and authority. A successful experience can be like the mentorship of an established artist. What occurs in the process of reeducation is both a transformation and collapse of understanding all at once. It resists systematization. Reeducation is an experiential practice with no stable framework or reliable center. It is a journey with no single direction—in and of itself a cornerstone of contemporary art practice: don’t become a method, and don’t become a mechanism.

(1)Shi Qing is not a professional educator, but has spent time leading art practice and installation courses in different fine arts academies. Some of his students have chosen to go into contemporary art after graduating, sometimes even creating work in collaboration with him.