A MAZE OF INTERSECTING VIEWS: 2ND SHENZHEN INDEPENDENT ANIMATION BIENNALE

| March 12, 2015 | Post In LEAP 31

TEXT / Sasha Zhao

Still image, single-channel HD video, 30 min 15 sec,

Courtesy of Wilfred Lentz Rotterdam

CURATED BY DONG Bingfeng with Amy Cheng among others, “Visions & Beyond,” the 2nd Shenzhen Independent Animation Biennale, opened on December 6, 2014, with parallel events occuring over the course of a year in Bejing, Taipei, Hong Kong, and back in Shenzhen. The first iteration of the Biennale was a comprehensive overview of the history and state of independent animation organized according to a definition of narrative image media. By contrast, the theme of the second Biennale suggests a point where image and animation intersect; with theory as its organizing principle, the exhibition is divided into a thematic exhibition and theatrical screenings, with design consideration given to the ways the image can be displayed. At the core of this Biennale is the thematic exhibition, which is designed to provide a clear path through the space; walls divide the space into a circuitous maze. Visitors are often required to move deep into a space for a particular work, then retrace their steps in order to continue viewing. To a certain extent, this increases the length of time a viewer will linger to watch video. Liu Wei’s nine-screen installation Colors (2013) is the opening piece in the exhibition, and raises doubts about the veracity of sight—scenes of everyday street life are cut with continuous flashes of high-purity fluorescent light, each interfering with the other. Colored neon tubes separate the sequence of images in space, emphasizing the viewing experience rather than the images themselves. In his video installation Learning the Flute (2003), William Kentridge uses a screen to imitate drawing on a blackboard, as well as his trademark technique of animated sketching. His source material is adapted from sketches for the opera The Magic Flute, and demonstrates the process of visual design for the work. Hito Steyerl’s video installation is set up as a boxing ring, with projection screens taking up the entire space. In her video Liquidity Inc. (2014), scenes are taken from live boxing and wrestling, GIFs found surfing Tumblr, and a masked announcer doing the weather forecast; the fluidity of water illuminates the reality of capital, unexpectedly juxtaposed with foam churned up by the waves of the internet age.

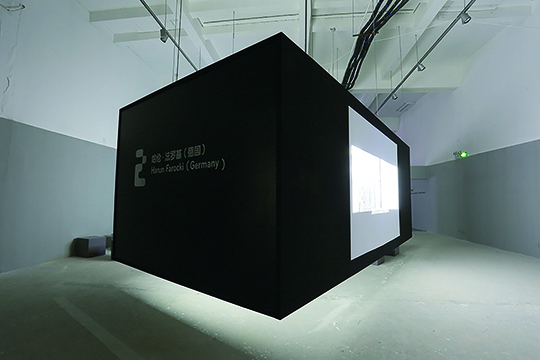

Harun Farocki’s three videos Workers Leaving the Factory (1995), Eye/Machine (2001), and Eye/Machine II (2002) are placed adjacent to both entrance and exit, allowing viewers to choose to begin from either end. The curators have deliberately brought the audience back to the beginning of the film era; the documentarian’s video thesis about labor concealed by industrialization reads as a response to contemporary Chinese understandings of image production.

Without negating the first Biennale’s definition of independent animation in contemporary art, the second Biennale broadens its terminology to redefine animation within the category of the moving image. The selection of works included in the exhibition includes film and several art forms derived from film, marking a return to thinking about the medium itself. Yuan Goang-Ming’s use of 300 photographs to make a composite of the empty streets of Ximending reminds us of Andreas Gursky’s realist depiction of photographic space; here the medium examines the identity of the city from the hybrid perspectives of the human eye and the machine’s field of view. Feng Mengbo’s video installation Keeping it Under Your Hat comes from an interest in images made by hand; during the opening ceremony a slide show he created in collaboration with Ji Zhou brought together shadows and pixels. Zhou Xiaohu’s clay stop-motion animation Intolerance is displayed as a video of the sculpture and, along with Liu Wei’s installation, is the loudest piece in the space. Kao Chung-Li’s film The Taste of Human Flesh, shown on a slide projector, turns film images with sound into a presentation of still images about 16 minutes long, using the montage produced by the projector to create a psychological experience outside the visual.

The cinema section is given equal importance, and focuses on the particular demands of displaying video. Screenings are held in two spaces, including the main exhibition hall and and an adjacent building. In one black box screening space, an improvised performance is added alongside the screening of work by Jodie Mack. In the satellite venue, Cong Feng’s two-hour documentary Stratum I and two of Zhou Tao’s films are screened, along with Zhu Jia’s short animation made during his experiments with the paintbrush.

The Biennale establishes an overlap between discourses of film and art history—from pioneering films of the 1920s, German animation of the 1920s and 30s, and computer animation from the 1960s onward to 16 mm experimental film, digital recording, artificial images, online video, and autonomous machine vision—with the underlying thread being the image itself. The Ouroboros—film in art history and experimental video in film history—creates a continuous cycle of meaning by devouring and producing history.

(Translated by Vanessa Nolan)