AD HOC ADMIRALTY

| March 28, 2015 | Post In LEAP 31

COLONIAL HONG KONG spread along the steep shores of Hong Kong Island. Land was so sparse that the British Navy’s headquarters were originally housed ad hoc aboard a ship, the HMS Tamar, which docked at the foot of Victoria Peak. Through successive reclamation projects, the colony grew into the City of Victoria and began to build, bit by bit, institutions and spaces including City Hall (1869) and Royal Square, later known as Statue Square after the statue of Queen Victoria was unveiled there in 1896. City Hall was replaced by the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank in 1933, and is presently the site of the HSBC Main Building, completed in 1985. On a perpendicular axis with Statue Square was the High Court Building, built in 1912 by Sir Aston Webb and Ingress Bell, a two-story neoclassical granite building featuring an ionic colonnade and dome surmounted by a replica of the statue of Themis atop Old Bailey in London. Vacated by the Court in 1980, it became the home in 1985 of the City’s Legislative Council (LegCo), the parliamentary body charged with administering the city since 1843. Originally appointed, and later directly elected, LegCo continues to function under the Basic Law since the 1997 handover to China.

In 2011 LegCo vacated the High Court Building for a new complex on a parcel of land recently reclaimed from the harbor on a site named for the HMS Tamar. Where the older building had the trappings of a western seat of government (dome, colonnade) as well as its provenance, the new complex resembles more a suburban office park or a luxury hotel. Designed by the Hong Kong architect Rocco Yim, the building is composed of two tower blocks bridged by a slightly askew horizontal cap. The effect, described as a gateway representing the transparency of government, is undermined by the thicket of towers immediately behind it, and by the general opacity of its surfacing. These ambitions are better exemplified in its podium, or multi-story base, which slopes downward towards the harbor with a widening lawn and connects via footbridges back over Harcourt Road to the city beyond it.

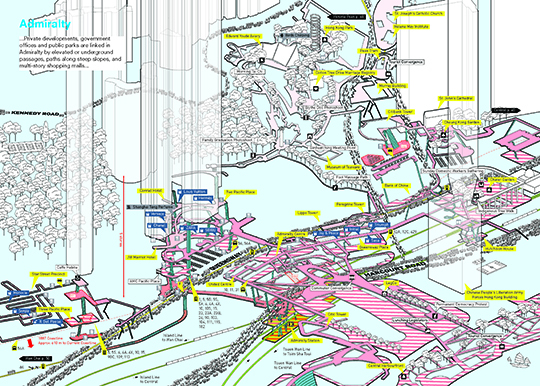

Unlike the centers of other cities, Admiralty lacks traditional formal expressions of state power or cultural identity found in either the eastern or western canons of architecture and urban design. The neighborhood has no center, no axis, no edge. There is no square, no boulevard, no significant monument. There is no symmetry, no urban fabric or grid. Admiralty, like Hong Kong, has no ground, culturally or physically.

To experience this, just take a walk from Hong Kong Park or Statue Square to Government Headquarters. This journey, which elsewhere would pass through formal sequences designed to express its significance, is a stroll through the haphazard and ad hoc. It is a walk up and down stairs and escalators, through the air-conditioned atria of shopping mall interiors, the narrow corridors of tower block lobbies, and liminal spaces of urban convenience such as catwalks beside public transit interchanges or parking garages.

Hong Kong is a political anomaly. It is certainly not the capital of anything, perhaps not even of itself. Nonetheless, it is a site of intense speculation with wide-reaching impact. How does political discourse play out in a city without traditional public space?

Shortly after its opening, Government Headquarters became the site of protest. Following Chief Executive CY Leung’s adoption of a new primary school curriculum that included content seen by many as apologist for the Chinese Communist Party, 50 members of a students activist group, Scholarism, occupied the public lawn beneath the LegCo complex. Beginning on August 30, 2012, the number of protesters would grow to 120,000 by September 7, spilling out over the footbridges, access roads, and other interstitial urban spaces surrounding the complex, and voicing a message directed as much against the government’s unresponsiveness as against the curriculum itself.

This protest, which dissipated after the government delayed implementation of the curriculum, presaged a longer more tumultuous one. Beginning on September 28, 2014 with an attempt by student activists to scale fencing that blocked access to Civic Square, resulting in turmoil during which police fired tear gas into the gathering crowds, a so-called occupation culminated in a sit-in by tens or hundreds of thousands of Hong Kong citizens in Admiralty and other sites throughout the territory. Organized on the ground by numerous organizations, including the student movement Scholarism and the advocacy group Occupy Central with Love and Peace, the movement had no central planning or coordination. Participants communicated directly by smartphone apps and responded to circumstances

as they developed. Occupying footbridges and sidewalks, as well as major roads, the movement engendered a temporary urbanism of barricades, stages, tents, and other informal structures that included recycling and trash pick-up, supply depots, delivery networks, phonecharging stations, medical, religious, educational and social programing, and more. The Hong Kong Police cleared Admiralty on December 11, 2014.

Recent political turmoil from Cairo to Kiev has centered on visible occupations of formal public spaces and streets. In Hong Kong, no street or square occupies such a symbolic place at the center of the city’s public life. Rather, the city’s public space exists in small-scale, ad hoc actions, appropriations, and occupations of private, public, and semi-public infrastructure. This is the territory of politics in Hong Kong. Like the space of the city itself, it is expedient and responsive. On exhibit at an exceptional scale during the occupation, these actions are in fact quotidian throughout the city. It defined the character of Hong Kong before the movement, and it will continue to do so even now that the occupation has ended.