All the World’s A Fair: On Art Fairs, Biennials, and Great Exhibitions

| March 18, 2015 | Post In LEAP 31

TEXT / Stephanie Bailey

TRANSLATION / Connie Kang

Lately it feels like all the world’s an art fair. —— Sarah Nicole Prickett(1)

When we talk about art fairs, we’re never just talking about art fairs. We’re talking about a world system that is fragmented, global, and populous: a global economy through which art objects (and indeed, art people) are circulated, exchanged, and valued among a constellation of figures and spaces, from artists, dealers, collectors, directors, and curators, to their institutional counterparts studios, galleries, foundations, non-profits, and museums. The art fair is a marketplace, or better yet, the art world’s agora: a space where economics, politics, and culture converge into a relational web that makes itself visible for about as long as a flash sale.

But how do we deal with such a bazaar, intellectually and ethically? At its worst, the art fair is an apparatus of security ruled by the laws of the free market,(2) which manages the movements and flows of a population and its production.(3) An event where, borrowing Paul Werner’s words, “the very admiring of art becomes an adherence to a free-market ideology.”(4) At best, an art fair is a social space: a kind of semiautonomous meeting place that enacts the role of a public square—albeit transient—for a fragmented global community. After all, as Amanda Sharp said of Frieze New York: “We do want to be more than a fair, in the sense that we always aimed to create a meeting place, a place where discussion could begin.”(5)

As a global phenomenon (there were 68 art fairs in 2005 and 189 in 2011(6), we might say the art fair is a space that reveals a “striking unity of microcosm and macrocosm.”(7) One that mediates, borrowing Pamela M. Lee’s words, “the homogenizing of culture on the one hand and the radical hybridity on the other.”(8) And expansion seems to be part of the art fair’s DNA (like other ventures of globalization, the British Empire being one of them). Borrowing Lee’s words again, it is “both object and agent” of a market system inextricably linked to the processes of globalization.(9) A process that, with the aid of technology, is charging ahead with what Lee describes as an insidious mantra(10) calling for “a ‘borderless’ world of smooth flows, unimpeded international travel, and ever-expanding networks of limitless communication.”(11)

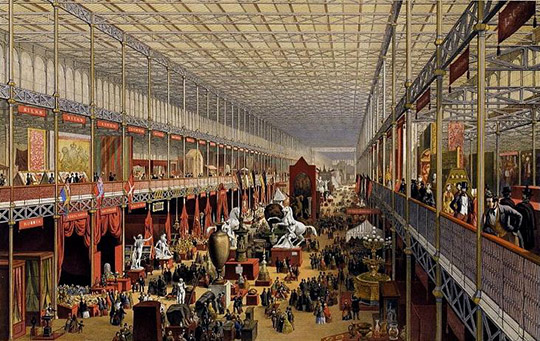

This has a historical precedent. Take Prince Albert’s description of the world in 1850. He talks about a dream of unity fast being realized thanks to the achievements of modern invention, which had caused a rapid vanishing of distances that once “separated the different nations and parts of the globe.”(12) One year later, the 1851 Great Exhibition of Works and Industry of All Nations took place in Britain—the first international exhibition, or World’s Fair—took place with 14,000 exhibitors from around the world. Celebrating “progress, invention, and British supremacy in world markets,”(13) the event was a game changer. As Dan Smith wrote, it helped shape western modernity’s formations of display, spectacle, and commodity arrangement and exchange.(14) One of the key aims of the fair was to promote a sense of unity and social cohesion through the production of social, economic and political networks on both national and international scales, thus consolidating the political agenda of its host, the British Empire.

But aside from enacting a vision of global unity with an international list of exhibitors, the Great Exhibition’s organizing committee was carefully selected to include members of all social classes, what Robert Rydell notes was a direct response to the socioeconomic conflicts of the time, encapsulated by Marx and Weber’s “Communist Manifesto,” published in 1848. As Rydell elaborates: “What was the response to the Communist Manifesto? Crystal Palace!”(15) In other words: a structure that enacts a kind of mediation through the soft power of culture and trade, or one that absorbs revolutionary forces into its fold. Indeed, one might say that the legacy of the 1851 Great Exhibition was the industrialization of culture, which ultimately led to the conditions Adorno and Horkheimer wrote about in 1947: the production of identical goods to satisfy identical needs in innumerable places,(16) not to mention innumerable formats through which to enact such a process.

Consider now Art Basel: “the virtual template of what art fairs are today.”(17) Founded just three years after the launch of the world’s first modern art fair, Art Cologne, in 1967, Art Basel is a replica, too.(18) Art Cologne launched a radically new way to present art outside the gallery and museum, and the impact was immediate. (Joseph Beuys’s Das Rudel became the first work by a German artist to surpass the DEM 100,000 mark when it was sold by René Block for DEM 110,000 in the 1969 edition.(19)) Even still, Art Basel became the largest art fair in 1973(20)—a success attributed to an international focus the fair established from the outset, in contrast with Art Cologne’s policy of admitting almost exclusively German galleries (even in its 2008 edition 65% of galleries were German).(21) It’s interesting to think about this now, given Art Basel’s expansive global reach, its adaptability, and its intentions for the future. (Recently, current director Marc Spiegler explained that Art Basel is entering its third stage of development—heralded by the fair’s recently launched Kickstarter campaign, and by the fact that the fair is now established on three continents.)

Nor is the biennial exhibition exempt from this history. As Charlotte Bydler notes, the 1851 Great Exhibition was a precursor of the internationalist dimensions of the modern biennial.(22) The Venice Biennale, which started in 1861 as a series of national exhibitions to celebrate Italy’s recent u nification a fter t he Napoleonic wars,(23) was officially launched as an International Exhibition of Art in 1895.(24) Today, it continues to organize itself in a format introduced by the World’s Fair with national pavilions, a somewhat anachronistic testament to its roots compared to yet another spawn of the World’s Fair idea: Documenta, launched by Arnold Bode in Kassel in 1955 as “a therapeutic agent to heal the emotional wounds of the Second World War.”(25) Documenta 5, staged in 1972 and curated by Harald Szeeman, became the first large scale art show to rebuke traditional modes of exhibition making—namely, hierarchical presentations formulated on art historical and fine art principles—by responding to conceptual contemporary art practices developing in a fast-changing world. Favouring “a central cross-disciplinary theme” and “non-chronological juxtaposition,”(26) Documenta 5 came to be known as the first Großausstellung—Great Exhibition—a fitting title. This was the Great Exhibition for the postmodern, global age, and it set the standard for how international biennial exhibitions have been curated ever since.

And ultimately, when it comes to these formats’ roots in the age of empire and industry, art fairs and biennials operate in similar ways. As Pamela M. Lee has said, biennials are cultural paroxysms of the modern nation-state(27) that have “come to stand as a country’s cultural point of entry into this global economy.” They enable, as Riyas Komu explained in 2012 around the launch of the Kochi Muziris Biennale in Kerala, India, a way to become part of a global conversation on autonomous terms.(28)

It feels like no coincidence, then, that Documenta 5 was staged only five years after Art Cologne was launched, or that the proliferation of art fairs in the twenty-first century has been matched by the increasing ubiquity of the biennial (over 150 biennials were counted in 2012(29)). In the end, art fairs and biennials operate as discursive, mediatory platforms of transaction, valuation and exchange within a global economy that has been propelled forward by the legacies of industrialism and capitalism. They are ultimately readymade frameworks through which forces of history, culture, politics and power commingle. Spaces that fit Keller Easterling’s definition of a “spatial product”—commercial infrastructures imbued with myths, desires, and symbolic capital that cut through borders, territories and politics, and which are exempt from normative jurisdictions and constituencies, like cruise ships.

Thus, when it comes to art fairs, which are—let’s be honest— the less palpable of the two formats under discussion, I think about Duchamp’s urinal. Fountain has been interpreted in a multitude of ways: an appropriation of an earlier gesture made by Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven; a ceramic replica of a gesture that commented on the role of industrial design; a rallying cry against the establishment; and an emblem of industrial progress. It is also an image by Alfred Stieglitz that has been circulated widely: a symbol of the mechanical processes of industrialization that have propelled modern capitalism and contemporary globalization. There is a memetic quality to Fountain’s existence: a work with a meaning that has changed—or rather, expanded—over time. Likewise, the art fair is a replicable format that has been adapted and refined to suit its market place and its patrons: a model with form that essentially stays the same, but evolves and adapts just like we do.

Indeed, as has been the case with Duchamp’s urinal, a commodity’s meaning—and value—is never fixed; when capitalism absorbs radical, dissenting forces, all is not lost. As a reflection of the culture of global capitalism shaping who we are individually, locally, nationally, and globally, the art fair is a negotiated space built from the relations that occur within it. Both an object of mutual contemplation and contention, it could be a site of potential if we wanted it to be.

(1)“The Rise and Rise of the Art Fair,” Sarah Nicole Prickett, The Globe and Mail, 2012.

(2)Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College de France 1977-78, Michel Foucault, Picador, 2009, p. 36.

(3)Ibid, p. 29.

(4)Museum, INC: Inside the Global Art World, Paul Werner, Prickly Paradigm Press, Chicago, 2005, p. 20.

(5)“The Rise and Rise of the Art Fair,” Sarah Nicole Prickett, The Globe and Mail, 2012.

(6)“Fair or foul: more art fairs and bigger brand galleries, but is the model sustainable?” Georgina Adam, The Art Newspaper, Issue 236, June 2012. Published online June 20, 2012.

(7)“The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” in The Dialectic of Enlightenment, (John Cumming), Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Verso, 2008, London, p. 155.

(8)Forgetting the Art World, Pamela Lee, MIT Press, 2012, Cambridge, MA, p. 4.

(9)Lee, 4.

(10)Lee, 14.

(11)Lee, 14.

(12)Introduction to the 1851 Great Exhibition as part of an exhibition curated by James Helyar. Courtesy of the Spencer Research Library, Kansas University.

(13)Traces of Modernity, Dan Smith, Verso, 2012, London.

(14)Ibid.

(15)“The Real Truth: A World’s Fair,” Robert Rydell, lecture at Raven Row Gallery, London, July 8, 2012.

(16)Adorno and Horkheimer, 121.

(17)“Art Stage Singapore 2011,” Woon Tai Ho, C-Artsmag.com, 2011.

(18)“The History of the First Modern Art Fair,” Günter Herzog, Artcologne.com.

(19)Ibid.

(20)“Mammoth Art Basel dwarfs world competition,” Corine Buchser, Swissinfo.com, 2010.

(21)Ibid.

(22)Lee, 12.

(23)“A brief history of I Giardini: Or a brief history of the Venice Biennale seen from the Giardini,” Vittoria Martini, art&education, 2009

(24)Ibid.

(25)“Documenta Goes Global,” Bernhard Schulz, The Art Newspaper, June 2012, pp 1-2.

(26)“1971 Harald Szeemann Education Notes: Investigating Artworks in the Gallery,” Kaldor Public Art Projects, New South Wales, 2009, p. 4.

(27)Lee, 12.

(28)Expressed by Komu in conversation with the author at the Sharjah March Meeting, March 18, 2012.

(29)World Biennial Forum Announcement: World Biennial Forum and Co-Directors