CONTEMPORARY CHINESE ART & ITS CRITICAL HISTORY

| March 25, 2015 | Post In LEAP 31

AFTER A FEW YEARS of discursive waffling about cosmopolitanism and international visual culture, Chinese contemporary art—as a distinct object of research and scholarship—is back with a vengeance. This spring (or, perhaps more appropriately, semester) sees the arrival of two ambitious new historical narratives of the genre, both of which will find their primary homes in the classroom. Contemporary Chinese Art, authored by the historian and curator Wu Hung, offers a straightforward history stretching from the end of the Cultural Revolution to the present, incorporating the new orthodoxy of the past half decade in the form of the mid-1970s No Name group, a broader understanding of the diaspora, an era of “normalization” after 2000, and other key interventions that would have been left out of the standard histories just a few years ago. Paul Gladston’s Contemporary Chinese Art: A Critical History, on the other hand, proposes a story of Chinese art through ideas, investigating how artists, theorists, and curators have engaged with the “dominant discursive formations” around them over time. Wu focuses the bulk of his argumentation on the 1980s and 1990s; after 1989, Gladston’s admirable intellectual history becomes an exhibition history instead; and after 2000, neither scholar has too much to add about new emerging art.

Whereas Wu’s art historical approach categorizes artists and moments based on social interactions and styles of work, Gladston instead looks at the references that inform artistic practices, and the philosophical stakes and affordances of these ways of working. Nevertheless, both books develop a system of periodization based on social and political events; art itself is never an agent in broader change. This system can make for awkward juxtapositions: dazibao posters, for instance, sit unproblematically next to Taiwanese modernism. Gladston importantly guides his reader towards the fundamental debate in which most players in the field are currently involved: that between a vision of contemporary art in China as a cosmopolitan branch of international art and an understanding of Chinese art as an essentialist and exceptionalist beast. Wu Hung is identified primarily with the former theorization, although his Contemporary Chinese Art makes clear that concessions to the exigencies of the system that has developed in China are probably even more important than their moments of interaction with international institutions.

Not unlike Johnson Chang’s recent theory of three Chinese art worlds (the contemporary, semi-official realism, and the neo-neoliterati), Wu responds to this question with three intertwining narratives: a “domestic movement” tied to political events and structures, a “global sphere” pushing and pulling on artists in China, and “individualized spaces” produced by artists between international institutions and official support. Gladston similarly goes to great lengths to problematize simplistic understandings of exchange between China and other parts of the world in his introduction. The stakes here for debate are now relatively low; both authors take a “just-the-factsma’am” approach to their work (as opposed to the ontologically additive interpretations favored by scholars like Gao Minglu, identified more with the essentialist strand of art criticism), and, like just about everyone else in the English-speaking side of the Chinese art world, they have settled on and incrementally improved relatively uncontested narratives. What seems left out here at the peril of a thorough understanding of our moment is the psychological power that the essentialist-exceptionalist narratives hold over art production and reception; these are the positions that are increasingly reflected in the state cultural apparatus and the ascendent Legalist-Confucian philosophical chowder it breeds, and so there is a project here that remains to be completed—an intellectual analysis that could understand the work of the art historian and the work of the artist in parallel terms.

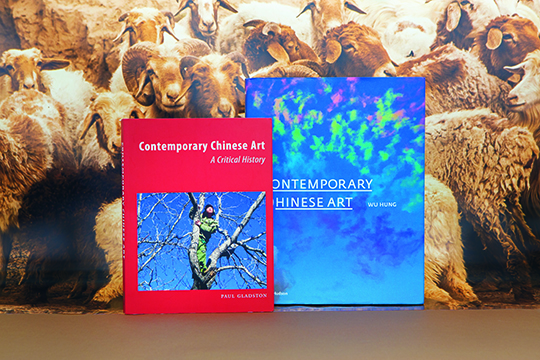

Wu Hung, Thames & Hudson, 2014, 456pp., English

Paul Gladston, Reaktion Books, 2014, 318pp., English