Invented and Incorporated: Subversive Complicity with the Capitalist Machine

| March 30, 2015 | Post In LEAP 31

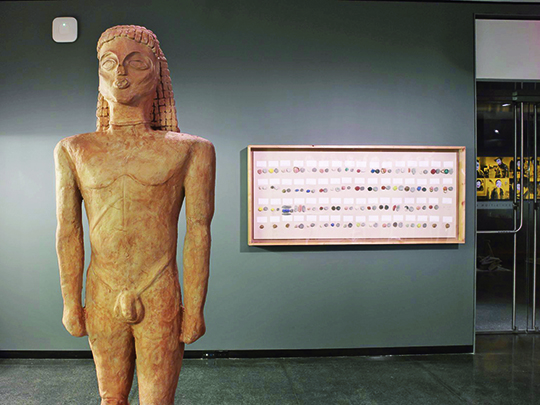

Within the current Shanghai Biennale, an artist by the name of Robbie Williams puts on a striking “Solo Show.” According to the official information available, Williams is an artist of Egyptian and Taiwanese heritage, born in Berlin, now living and working in Stockholm. The familiar materials that make up “Solo Show” seem to point out a few evident patterns in contemporary art: disparate installations suggest an underlying abstract narrative almost reducible to some sort of formula, effortlessly putting on the kind of thing one might find at a biennial. But any reading of Williams’s aesthetic language is futile, because the artist does not exist, and the author of these works does not point to a singular identity.

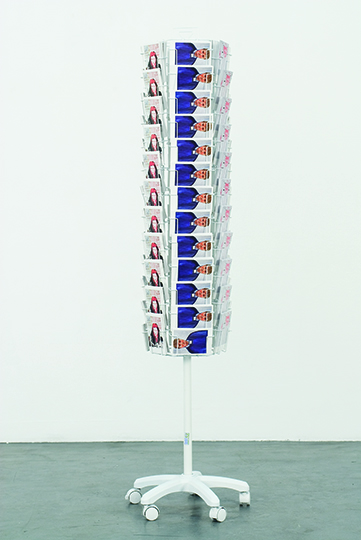

Robbie Williams’s “Solo Show” is a collaborative project by artist Natascha Sadr Haghighian and Uwe Schwarzer, founder of Berlin-based art production company mixedmedia. Haghighian invented Robbie Williams and commissioned mixedmedia to create all of the works in “Solo Show.” mixedmedia is a well-known establishment in the industry, counting Liam Gillick, Monica Bonvicini, Carsten Höller, and Olafur Eliasson among its clients. The works that mixedmedia produces, however, can never bear its name; the company takes pride in faithfully manifesting the artist’s vision, and so remains largely unknown outside the field. Its clientele explains the sense of déja vu in “Solo Show,” but no single artist’s name comes to mind.

Another crucial part of “Solo Show” is a list of names of all the workers involved in the production, spread out on the wall like the ending credits of a movie. Though not all collaborators wished to have their names displayed this way, by announcing them, Haghighian calls attention to the division of labor in art production, attempting to demystify the process while probing the question of authorship in contemporary art.

A fictional artist’s identity is certainly not a novel thing, and choosing a ubiquitous and humorous name like Robbie Williams highlights the very act of inventing or borrowing this readymade identity, rather than poking fun at viewers, collectors, and media. (Some Chinese media did believe that Robbie Williams was a real Taiwanese-Egyptian artist, but this does not represent the general level of intelligence of art audiences today.) Distributed at the biennial as a part of “Solo Show,” the publication IINN PPEERRPPEETTUUAALL PPRROODDUUCCTTIIOONN includes an essay by Stephen Squibb, using the terminology of Marx’s Capital to discuss Duchamp’s Fountain and the antimony between art and commodity. He suggests that artworks and commodities are mutually contradictory, while their dialectical existence relies on this dichotomy. Duchamp’s Fountain, signed “R. Mutt,” relies on the disparity between art and commodity for effect. Its rejection of function benefits from the democratic system of the erstwhile Society of Independent Artists, but it is not a critique of the system; it accepts the opportunities that the system provides. The same logic can be applied to the identity of the fictional artist. There is no inherent difference in naming an artist Robbie Williams, John Doe, or Tommy Bahama, because we know that, in the media-inundated present, all public identities are created or affected by subjective consciousness. As Duchamp’s refusal of a fixed identity was a response to the society’s unstable political and economic factors at the time, contemporary artist identities’ artificiality, performativity, and maneuverability also speak directly to the system of contemporary art itself. The art world, accordingly, is highly welcoming of practices that exemplify a kind of hyperawareness and self-reflexivity, and absorbs them into its capitalist operation.

Inventing a fictive identity for a contemporary artist is often a strategic response to and exploitation of the system itself, pointing out the idiosyncratic political rules and contradictions of the art world. In her essay “Human Strike within the Field of Libidinal Economy,” the artist Claire Fontaine writes, “We have invented ourselves, so to speak, the social contradictions that made our freedom necessary. Where invented doesn’t mean made up, but found and translated, the facts that reveal their dormant political dimension.” Fontaine—a readymade artist persona—takes her name from a famous French stationery brand. Her identity was a creation of Paris-based artists Fulvia Carnevale and James Thornhill. They call themselves assistants to Fontaine, creating and exhibiting work under this singular female identity. Assuming another identity here is not an escape strategy, but rather establishes a new lexicon to confront feelings of political impotence and powerlessness. Political impotence is both the subject and means of Claire Fontaine’s work.

In the context of contemporary art, an exploration of political impotence naturally questions symbolic practices. If a political stance cannot affect the real world, then it is simply a gesture, a metaphor concealing potential in impotence. Compared to her prolific writing, often in the form of political manifesto, Claire Fontaine’s artistic language speaks to classical notions of the formality of art by way of détournement. Sometimes, obvious references and parody of minimalist materialism seem too straightforward. In La Société du Spectacle brickbat, the materiality of the brick is a direct reference to the minimalist artist Carl Andre, implying the impotence of Debord’s revolutionary text; on the other hand, the brick, being a weapon, endows The Society of the Spectacle with new potential for revolution. Producing visually stimulating and memetic objects is not intended to drive a practice; like the use of the readymade brand name, it is a branding tactic to attract interest and generate publicity. Fontaine herself admits that she has no obligation to escape the workings of capitalism, because nothing in contemporary society exists outside this framework. It doesn’t help anything to simply call exhibiting and selling work in a gallery system complicity with capitalism. Critic Craig Owens uses the phrase “subversive complicity” to describe the equivocal approach with which postmodern artists put their art in the marketplace; it is equally fitting to use this term to describe many artists who use fictive identities in the contemporary art world.

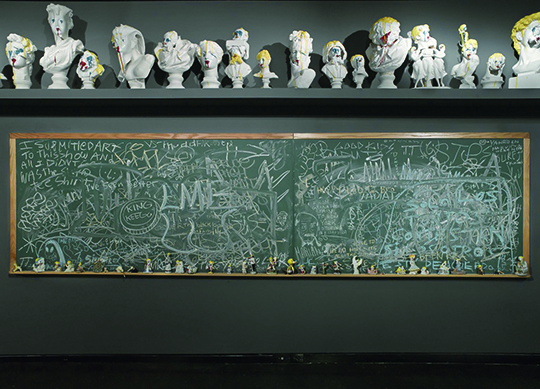

It is no coincidence that the work of Claire Fontaine and Robbie Williams resemble other artists; using a visual language with which the art world is acquainted calls into question the production of contemporary art itself. That we find Fontaine’s name among mixedmedia’s list of clients further verifies this point. Another pseudonymous art group, Bruce High Quality Foundation (BHQF), uses a more radical and subversive method of directly quoting art history, challenging the recognition of the artist’s persona. BHQF is an anonymous collective established by a group of students from Cooper Union in New York in 2004. Inventing an artist named Bruce High Quality, who supposedly died in the 9/11 attacks, the so-called foundation’s stated aim is to pass his legacy on to future generations. No one knows the names or structure of its membership, as all members refer to themselves as “Bruces.” They are known for their public mockery of classic works and the mechanisms of art, as in their early “Public Sculpture Tackle” series, or their “Brucennial,” and the ongoing project “Meditations,” which uses Play-Doh to replicate the antique collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

To ensure that their autonomy remains free from the interference of individual artists’ narratives and to contend with the mechanics of celebrity, the Bruces emphasize their anonymity, refusing to give their names or personal information to the media. But even if their identities are unknown, their faces have gradually become familiar in the New York art scene, and it is precisely this kind of playing around with artists’ identities—a kind of bait for PR antics—that attracts collectors and the market. This self-referential, teasing approach is exactly what amuses the art world. Contrary to Robbie Williams’s emphasis on every worker involved in the production of his work, BHQF’s production process and division of labor is opaque, which subsequently increases the value of the work’s abstract labor on the market.

Ten years before Bruce High Quality Foundation, downtown New York witnessed another art group who called on the weak corporatization of individual identity—Bernadette Corporation. But unlike BHQF’s genuine corporate operating structure, Bernadette’s “corporation” is merely a pretense. From their inception, Bernadette Corporation showed that the inescapable controlling force of capitalism actually made them free. They take a stand against art, rejecting the context of solemnity, segmentation, and rarity in the art world. From the initial club nights to later clothing label, magazine, novel, and installations, the majority of Bernadette Corporation’s creative output consciously borrows the aesthetic language and production modes of commerce. They encourage young creatives to renounce the delusion of individual expression in art, exploiting to the utmost the power and freedom offered by the commercial system and economic networks. John Hill, a member of the London art collective LuckyPDF, evaluates the situation: “Bernadette Corporation shows the power to disrupt by fully embracing. There’s no need to use art to model doing something when the world is a place to actually do it” (published in the October 2012 issue of Dazed). In a similar fashion, LuckyPDF plays the role of a television station, party promoter, and clothing label in their practice. These cultural products appear to be outside the category of art, but they are still framed as the practice of an art collective. Bernadette Corporation’s conscious embrace of and participation in capitalism is, in a roundabout way, an artistic tactic, exploiting the freedom of language brought about by existing as a corporation, but not truly actively participating in the workings of capital.

In 2004, Bernadette Corporation organized the collaborative writing of a novel by some 150 anonymous writers of differing backgrounds, creating the life, identity, and narrative of Reena Spaulings, a New York “It Girl.” Reena Spaulings has since taken on a life of her own—today, she is an artist, gallerist, curator, filmmaker, and musician, as well as an artwork and commodity in and of herself. Reena Spaulings, along with the gallery that bears her name, is active in the exhibition and market systems of contemporary art. Reena Spaulings’s multilevel participation in the capitalist game of contemporary art gives her a more embedded critical stance, though this self-reflexivity doesn’t necessarily translate to criticality. The symbolic politicized stance in the art of Bernadette Corporation and Reena Spaulings, as well as their actual political impotence, is in itself part of a game with its own rules, perpetuating a kind of complex, subversive complicity.

Writer Brian Droitcour calls BHQF and LuckyPDF “Young Incorporated Artists” in his eponymous essay featured in the April 2014 issue of Art in America, seeing their corporatized, collective discourse as a tactic of participating in the Monopoly-style game of art. Among the artists he looks at, K-HOLE ’s work is particularly prominent. K-HOLE is a trend forecasting group. Though its five members are clearly identified, their individual voices and identities are unified and homogenized in the collective’s commercial language. Most people know the group because of their coining of the popular term “normcore.” Because of K-HOLE ’s total embrace of commercial language and aesthetics, very few know their background or analyze them in the context of art. K-HOLE ’s complicity with the corporate system outside of art goes even deeper than that of Bernadette Corporation. Their work centers around seasonal trend reports, published in PDF format on their website. One aspect of the aesthetic and language of marketing in their reports attracts collaboration on business projects. Another aspect, seen by the art world, is a practice of infiltrating, subversive critique. It is hard to say how much of their work is critique—as Droitcour says, the art world often confuses self-referentiality and criticality. But the level of infiltration and influence their work has had on the commercial cultural landscape is already much greater than the subversion any young artists can inspire. K-HOLE ’s complete refusal of language outside that of branding draws attention to the interdependence of systems for art and enterprise.

When an artist’s identity is fictionalized or corporatized, it is a tactical intervention of contemporary art in response to the capitalist machine, a practice of hiding destructive potential in a complicit attitude. These fabricated identities in contemporary art depend on the system itself; their self-referential and game-playing practices are frequently regarded as clever institutional critique and then further absorbed by the art world. As Boris Groys says in the preface to Going Public: “There is no doubt that any public persona is also a commodity, and that every gesture towards going public serves the interests of numerous profiteers and potential shareholders.” In the face of an inescapable capitalist structure, formalized imitation of the artifice and power of the capitalist game is now an effective tactic for contemporary art to participate in the capitalist system, even if this becomes a cycle of collusion. The symbolic practice of political impotence may be always-already consumed, a gesture with no consequence, but it retains the half-hearted promise that, one day, its subversion may yet come into effect.