SOCIAL FACTORY: 10TH SHANGHAI BIENNALE 2014

| March 12, 2015 | Post In LEAP 31

POWER STATION OF ART, SHANGHAI

2014.11.23~2015.03.31

CRITIQUE I

TEXT / Lu Mingjun

Translated by Daniel Nieh

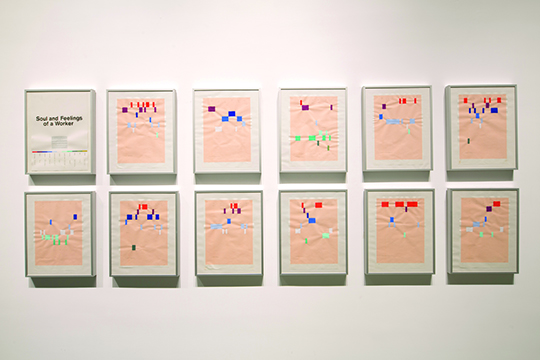

More than 70 artists participated in “Social Factory,” Anselm Franke’s Shanghai Biennale. This edition of the event is markedly less grandiose than previous years, and the atmosphere less raucous. Anyone familiar with Franke’s curatorial style knows that knowledge and ideas dominate the planning and framing of his exhibitions, including his selection of artists. There are no towering spectacles or special gimmicks to speak of; his exhibitions lack rhythm and might even be described as colorless. In Shanghai, his subject is a conventionally themed group exhibition that represents recent trends toward anthropology and research in western curation. It is determined not to be viewed or experienced; it would prefer to be read and considered. Franke’s approach is more sober and restrained than ever.

“Social Factory” is no longer a massive social narrative and cultural critique; instead, it is a microcosmic consideration of the internal systems and mechanisms of society. This perspective is rooted in local history and reality, but the exhibition outlines social systems of a global nature. It does not center on Shanghai or China, and the participating foreign artists function as more than symbols of internationalization.

Franke frequently references the modernist woodcut movement of 1920s Shanghai in the exhibition, which he feels embodies the dramatic dialectical relationship between the subjective perceptions of popular thought and the objective structures of social reality, revealing the transparency of certain social mechanisms. In this way, a tension permeates the entire exhibition, which otherwise lacks a rigid overarching structure or design. Viewers nonetheless sense and recognize interconnected layers and threads of the social mechanisms of power, cognition, and energy. In The Whole Truth, Lawrence Abu Hamdan bypasses written communication and uses the automated analysis of human voices to test reactions to apprehension and anxiety. It is the same method used by law enforcement and other government organs to detect lies in polygraph tests—a method of control. Neil Beloufa’s World Domination employs facetious language in a metaphor about regional power plays in the context of globalization, while also suggesting that any exercise of authority itself constitutes a kind of internal self-constraint. That is to say, power is intrinsically double-edged. As Franke sees it, his purpose is to present a political theater.

“Social Factory” represents a continuation of the logicand methods of “Animism” and “Modern Monsters,” but it goes beyond discussions of anthropocentrism. This exploration of the mechanisms of cognition and power represents a deepening of Franke’s reconsideration of modernity. As Nicolas Bourriaud sees it, this examination of our materially oriented era—perhaps a speculative realist one—is itself a dramatization of the loss of human subjectivity. Franke disagrees, insisting on the importance of flexible subjectivity. In fact, this exhibition contains revisions of his previous viewpoint, at least with regard to the mechanisms of social power and their internal tension. Here he subtly reaffirms mankind’s subjective initiative and volition.

The true problem is that the exhibition seems to lack a necessary awareness and consideration of the art system itself. On the one hand, Franke considers the constraints of subjective knowledge; on the other, his curatorial philosophy, including his selection of artists, reflects an emphasis on weak visuals and anti-spectacle. He critiques the engineering of modernism, but, at the same time, the spatial arrangement and overall aesthetic of his exhibition express a highly modernist, formal narrative structure. This method of reading—opposed to experience and even artistic identity— is, in fact, the predominant force in modern discourse. As a mainstream exhibition typology, it has already become a new value system.

CRITIQUE II

TEXT / He Jing

Translated by Daniel Nieh

Placing art and beauty within the framework of social change; viewing aesthetic activity as a route to human liberation—these ideas are products of the western modernity that began in the eighteenth century. In On the Aesthetic Education of Man, Friedrich Schiller, an important figure of German Enlightenment literature, critiques the adulation of utilitarianism prevalent in his time. He posits that aesthetic activity and artistic work are the core drivers of social change. Aesthetics and art education play a key political role in the process of human progress. In China, this approach was embraced by the democratic revolutionary Cai Yuanpei, who advocated a cultural reform program of replacing religion with art education during the May Fourth movement. “Social Factory,” led by chief curator Anselm Franke, does not stray far from this traditional debate over the role of artistic creativity in rethinking modernity. The exhibition draws connections between actual social circumstances and subjectivity within the framework of modernism. By casting about with its microscope, this edition of the Biennale explores how art, as a kind of political consciousness, constitutes a means of participating in contemporary society and the process of modernization.

In the curator’s statement, Franke raises Liang Qichao, Cai Yuanpei, Lu Xun, and other early Chinese modern reformers in order to trace the thread of culture and art as experimental driving forces for social change within a Chinese context. Another contextual reference point is to “seek the truth from facts,” the exhortation employed by both Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping during different periods of Chinese political reform. The expression took on certain political connotations after it was widely coopted by ideological propaganda, but Franke restores it to the framework of philosophical debate. He uses its concept of “fact” to reaffirm the importance of subjective production within the process of modernization. As Franke sees it, subjectivity is a relational fact that connects the individual to implicit social scripts, including perception, imagination, emotion, and other ideas that intertwine society with aesthetics: “It is within the realm of image-making and cultural production that we comprehend truths about the complexity of social relations that otherwise remain inaccessible.” This strategy of social evolution led by art indeed matches the critique of modern rationality by traditional Romanticist aesthetics, but Franke does not adopt a position of anti-modernism for this edition of the Biennale. Rather, he takes art as a means of revealing the hidden structures of contemporary society. By zeroing in on the subtle links between the modernist framework and subjective consciousness, the exhibition explores the sustained significance of modernization in the context of the nation-state.

In fact, Franke’s habitual use of historical frameworks and anthropological perspectives delineates the primary formal grammar of the exhibition: photographs and archival documents presented in display cases, alternating objects and installations, hanging suspended images. Of course, these modes have long been conventional in contemporary art exhibitions. The uniqueness of Franke’s approach is that the entry points for viewing and understanding that he provides are located in the details. In other words, this edition of the Biennale includes no spectacular forms of art, nor is it possible to become rapidly immersed in the works from the outset. The audience must spend a certain amount of time standing still, observing, listening, reading, and imagining in order to find the entry points to various works and the ties that bring them together. This requirement reflects the subtle relationship between the cognitive grammar employed by the curator and the exhibition’s thematic goals. The Shanghai Biennale emphasizes historical imagination and narrative desire, temporally interconnected throughout, over phenomenological or spatial experience. This allows the audience, guided by the cognitive frameworks that the artworks generate, to imagine subjective discourses within specific contexts of social production. By focusing on the narrative frameworks of specific works rather than the relational networks they form, Franke’s perennial preoccupation with subjectivity itself becomes evident.

These demands on systematic knowledge and nuanced logic may be the greatest effects of this edition of the Shanghai Biennale. It is also a test of Franke’s aesthetic thinking and exhibition methodology can bring anything to the local art ecology. Forgoing a segmented exhibition structure enables a narrative language of complexity and interpretive depth, but the dearth of large-scale work denies the fantasies entertained by many potential Biennale visitors. How might a departure from spectacle allow indigenous creative and curatorial practices to reach a more refined plane is, perhaps, a question that a new generation of artists and curators will be willing to address together.