Superartists: Production Tactics of Corporatization in Art

| March 28, 2015 | Post In LEAP 31

TRANSLATION / David East

ILLUSTRATION / weiwei

Zhang Huan has worked in a 100-person factory—almost a genuine enterprise—in the suburban Songjiang district of Shanghai since 2005. Cai Guo-Qiang’s studio employs 16 people, the multinational team working to meet the differing needs of three to five exhibitions a year in various countries on the shortest timescale possible. Takashi Murakami proposes in his autobiography Art Entrepeneurship Theory that “art is the business of imagination,” almost a slogan to inspire the Chinese contemporary art world. He provides the best reference information for China’s “superartists.”

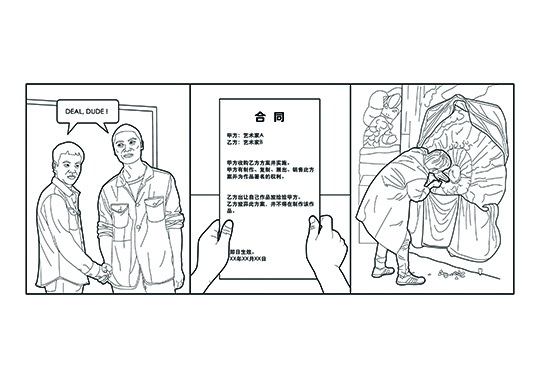

These superartists are unparalleled in their production efficiency because the teams behind them take on the external work of production, manufacturing, and publicity, as well as assisting the artist in planning, research, analysis, response, and coordination—a creative team with the artist as nucleus. Compared to the factorystyle productivity of these superartists, strictly individual work is clearly at a competitive disadvantage. Employed at the studio of the superartist, art students and local technicians cooperate and divide labor, forming simple industrial relations with the artist. For young artists, it is a way of compromising on the path to professionalization. Superartists surpass the power of the individual at the cost of the elimination of individual creativity. Proper division of labor and resources are integrated into the art studio as a more powerful organism, forming an adaptable super-system.

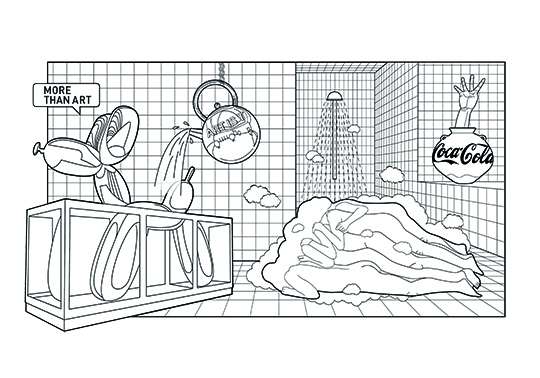

Following the dominance of the mega-galleries, the birth of the superartist seems to be in tune with the needs of the art market. For artists feeling the pressure of the seemingly unchangeable cycle of the gallery consignment system, the unfairness of the international market’s pricing can bring about future price bottlenecks. Corporatized superartists seem to be born out of an inevitable trend: having power over discourse guarantees, at least to some extent, the power to set prices and direct their career development. A disciplined team working under pressure has an obvious advantage in manufacturing, publicity, and cooperation with institutions. It can also respond promptly to external changes in valuation on the market. Cai Guo-Qiang has taken full advantage of the social capabilities of the artist with discursive power by weaving an environmental message into his artwork, referring to smog and a infamous incident in which 16,000 pig carcasses were seen floating down the Huangpu River near Shanghai. Effective use of branding and institutions, self-promotion through events, and making an impact on society: this is the modus operandi of the superartist.

X+Q is a brand created by the husband-and-wife team of sculptors Qu Guangci and Xiang Jing, with offices located in Beijing’s central business district. Established in 2010, its staff work in product development, branding, design, public relations, and marketing. The product line is based on the artists’ work, selling parts of original works or reduced-scale versions. Some of the works are handmade, limited editions bearing the artist’s signature. In its marketing material, however, X+Q emphasizes that it is independent from the artist and non-commercial, using the neutral term “gift” to blur the distinction between artwork and commodity. At first it was seen as pushing out derivative works, and didn’t receive much of a reaction. But artists gradually began to realize its importance, emphasizing its brand name, its luxury gifts, its downtown retail store, and its promotional collaborations, emulating the customer loyalty and cohesion of commercial brands. It is a proactive way to seek added value, extend merchandising, break the barriers of the art market, and develop further avenues for the success of original work.

Assembling a team is based on the mutual fulfilling of needs. Compared to loose groups pieced together for simpler creative or manufacturing needs, the corporation was established specifically for mutual benefit. Large-scale production is more efficient and stable, allowing individual strengths to stand out. As a result, corporations have become a tactic for artistic creation. They allow young artists the chance to work in the art world; operations like X+Q also allow artists to break away from the activity of the art market by operating physical or online stores, while still continuing to create value for their work. This is the emergence of conventional business logic. On a more practical level, it also offers a way out for artists who lack the funds to continue creative work, or who work in difficult installation formats; there is, after all, a certain inspiration in corporate organization.

Xu Zhen does not choose to draw direct support on his accumulated art world capital to create a super-Xu; instead, he gave up his own name, working from 2009 to 2014 under the desubjectivized label of MadeIn Co., making use of his corporate identity as a more convenient way to get involved in every aspect of the art world. In Shanghai, where the company has executive, creative, and manufacturing divisions, Lu Pingyuan and nearly 30 other artists work together in varying capacities. They have monthly salaries and health insurance; in a real sense, they are office workers. They have frequent brainstorming sessions like an advertising company, and conduct themselves with military precision. The merchandise MadeIn trades in is abundant: painting, photography, video, installation, sculpture, performance, and mixed media. Xu no longer works as an individual artist; instead, he hands over complete responsibility for project management to assistants, and sometimes even relinquishes control entirely to allow his assistants to carry out their own proposals. The entire factory operates autonomously. Xu’s practice follows Jerry Saltz’s market logic: “The artist is a brand, and the brand supercedes the art.” Unlike the situation the superartists face—companies established to meet the demands of processing and manufacturing—MadeIn borrows from the core of corporate organization to resolve questions of investment capital and legitimacy, but its management structure is simple compared to regular companies.

But the MadeIn superartist experience (buying and reorganizing others’ knowledge, refining recent work, placing orders to create work) is hardly Xu Zhen’s first experiment with defining the corporation. Beginning with running Shanghai’s BizArt Art Center, Xu has consistently hidden his work in the background of his companies, a form of anonymous production tied to the artist’s consideration of the systems in which he works. In 2013, the exhibition “Movement Field” put forward the concept of Xu Zhen as a brand under the MadeIn mantle; in 2014, MadeIn Gallery was established, presenting artists Lu Pingyuan, Ding Li, and Xu Zhen at the Armory Show, as well as solo exhibitions for Wang Sishu and He An in their M50 art space. At the ART021 fair in Shanghai, Xu and collector David Chau launched an art product store called PIMO, selling works in the RMB 100-200 range in an attempt to knock art off its pedestal and draw attention to its commercial attributes. All of Xu’s work brings flexibility to the idea of the corporation, allowing us to view the thinking and method behind artistic production: he takes advantage of the western art world’s tastes, speeds up the production output of his work, uses the relatively low prices of Chinese art galleries to dump product, and leverages the influence of sales to change the discourse between artists and the galleries that represent them. Its significance lies in artists’ struggle for space for survival and growth. Of course, Xu’s tactics can be seen as a satire of the superartist’s complete commodification of art today.

With the help of his corporation, Xu Zhen relinquishes the identity of the artist, taking the scope of his work beyond the existing gallery-curator-collector paradigm and allowing patterns of creation, production, and collection to appear more clearly. With the help of his social capabilities and the removal of legal barriers to entering the market, he has become a link in the chain of art production—albeit one with a multifaceted and unconstrained identity. When it comes to the future of the corporation, could any hypothesis be more unconventional?

For a 2013 exhibition at Beijing’s White Space, Hu Qingtai displayed eight artists’ proposals for artwork in the series “I Purchased and Executed Proposals,” carrying out their plans and signing the resulting works with his own name. This process bluntly calls into question the concept of authorship in art: what happens when an artist carries out a project, but is not its creator? To some extent, the project reveals a key link in MadeIn’s supply chain. The inspiration for the modularity and pliability of Xu Zhen’s work is based on opening up authorship, dismantling the artist’s unique ownership of his work, opposing the market dominance of the collector, and downplaying the mass reproduction of art.

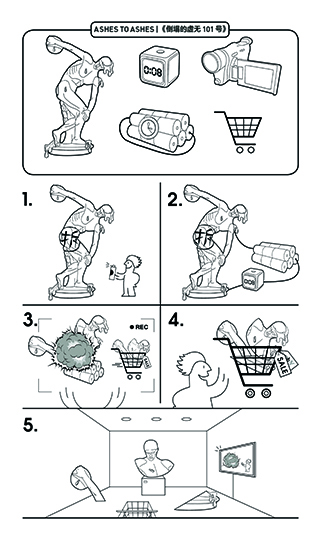

From the producer’s point of view, the corporation reacts to capital’s centralized standardization of production by capital. In the case of contemporary art, this becomes a sort of Ikea-ism. Ikea’s method was first established on the basis of large-scale production that maintains the flow and maturation of research and development and production technology on a global scale, following designs to completion and allowing each phase of design to become more independent and streamlined. Differing departments work in sync, making the gap between inception and realization very short. At the same time, a super-system like Ikea supports the originality of each creator, opens up the design structure, gives the responsibility of assembly and installation to the consumer, and eliminates uniqueness in design. Ikea-ism reflects the power structures of the current art world.

If art has the potential to become an easy-to-follow process, opening up the power to produce to everyone and liberating authorship, can the aura art be erased? Just as the popularization of film forced artists who had previously pursued realism to escape the standards and methods of the time and pursue innovation, will we ever see a true Ikea in art? This depends, to a large degree, on a potential increase in the population of art consumers and the presence of art in the life of the everyday consumer life in China. If art becomes a new demand for consumers to the extent that viewing and buying art becomes part of the e-commerce mainstream, an experience that diverges from the rules and regulations of today’s art world could emerge. The conjecture that art will become an essential part of life is here inverted.