PAUL CHAN: ENTHUSIASM TRAP

| July 14, 2015 | Post In 2015年6月号

Every two years, the Guggenheim Museum administers the Hugo Boss Prize. Funded by the eponymous German clothing company, the prize is presented to an artist “whose oeuvre constitutes an outstanding contribution to contemporary art,” as determined by an independent panel of curators and critics. In 2014, 42-year-old New York-based artist Paul Chan won the Prize’s tenth iteration, receiving USD 100,000 and a solo exhibition at the Guggenheim that ended in May. Chan’s is a multidisciplinary career. Having begun with animated works like the Henry Darger-and Charles Fourier-inspired Happiness (Finally) After 35,000 Years of Civilization (2002) and the Pier Paolo Pasoliniand Biggie Smalls-featuring My Birds… Trash… The Future (2004), his endeavors have included a post-Hurricane Katrina rendition of Waiting for Godot in New Orleans, the creation of the publishing outfit Badlands Unlimited, and essays on subjects ranging from visiting Baghdad during the Iraq War to Theodor Adorno’s legacy—for all of which Chan has been resoundingly celebrated.

In an online Wall Street Journal piece that ran after the prize was announced, Chan declared he’d “go big” with the exhibition. “When people are unsettled by something or find something ridiculous, then you know you’re going in the right direction.” What might Chan, known both as a politically engaged artist and as a bit of a troll, do with money and space presented to him by a fashion company relevant primarily for awkward atonements for its Nazi past and a museum empire building an outpost on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island with migrant workers subjected to conditions akin, as the Guardian reported, “to an open air prison”?

PHOTO: Donn Young

Courtesy Creative Time

Not much, from what one could glean at the press preview for “Nonprojections for New Lovers.” In lieu of Chan, who didn’t attend, Guggenheim officials gave remarks. Attendees received luxurious, leather-bound catalogues containing artist projects and the requisite essays on each nominee. Chan’s offering features crudely rendered 3D models of ancient Athens juxtaposed with Venn diagrams of Greek architectural features and associated philosophers (the Stoa Poikile and Zeno, for example) and various sorts of animal protein. The project ends with a yellow Post-it note, reading, “1. old cloak 2. bare feet 3. the end.” Post-internet artist Petra Cortright wrote the accompanying essay, which features the ADHD references and jittery webscrawl we’ve come to expect from her generation (also mine): “x_x,” “Sara Michelle Gellar in the year 2012,” “The issues address fifa fifa 12 cheat FIFA Soccer XBOX Fifa.” More importantly, however, with regards to Paul: “the smartest ‘Asian Thumbnails’ motherfucker methn+crystal PEKINPEKIN HOTELS Pekinese dog I know ya ya ya! And he talks like a fucking fuking black boys Fulbright scholarship philosopher.”

The show itself is sparse. Strewn on the ground are various projectors, with power cords running to jury-rigged outlets extruding from concrete-filled shoes. The works’ titles pun on those of Greek philosophers: Diogenes becomes Die Jennies, Socrates Sock N Tease. While the bulbs f licker, the machines project nothing—hence the exhibition’s title. Mounted high on a wall is Tetra Gummi Phone, consisting of cloth tubes undulating outward, animated by industrial fans. While it mostly resembles the wacky waving tube men one sees outside of used car lots, we’re told that, as another “nonprojection,” the work takes up the Greek concept of pneuma, meaning both breath and soul.

Courtesy Creative Time

Paul Chan actually retired from art-making in 2009, deciding to “make books in the expanded field” with Badlands Unlimited, which he launched in 2010. Accordingly, Chan, who came out of said retirement with an exhibition last year at the Schaulager in Basel, uses the prize to mark (and fund, presumably) Badland’s launch of New Lovers, a series of erotic fiction inspired by Olympia Press, a mid-century French publishing house known for erotica and avant-garde fiction. In the exhibition, proofs of the books sit behind glass, marked up with notes on title length and font size. One could look inside the books in the gift shop, we were told.

So little to see! Or, so much not to see, and to be told that we are there to not see it. There is a lingering sense that we are being purposefully underwhelmed, an apprehension briskly shunted away by most critical response. Longer form pieces or interviews with Chan focus on the more decipherable New Lovers and Badlands. Those who focus on the exhibition itself end up with platitudes about rethinking what art might be. “Mr. Chan’s work is always surprising and as smart as art gets, which means, among other things, that it’s smart enough not to always give us the art we think we want,” writes Holland Cotter in the New York Times, without offering much on what we’re given and why it’s so smart. “The non-projections themselves may be frustrating, but they make us rethink our expectations of what should be on view in a contemporary art museum,” says Orit Gat in The Art Newspaper, as if these expectations aren’t already endless debated. This equivocation makes one wonder if Chan made a purposefully unrewarding show not to point out a blandly Adornian point about irrational contingency embodied by art’s refusal to be subsumed by society, but instead to show how quickly people would ascribe such a point to the work.

For a brief period I was unsure that Paul Chan existed. I began to follow Chan in 2007, before I began writing about art, with Waiting for Godot in New Orleans: A Play in Two Acts, a Project in Three Parts. As the subtitle suggests, the project encompassed not only the play, but also eight months of various community engagements in New Orleans undertaken by Chan and collaborating institutions Creative Time and the Classical Theatre of Harlem, as well as the establishment of a “shadow fund” of some USD 50,000, which provided financial support for local organizations engaged in rebuilding efforts for the areas that hosted the production.

PHOTO: David Heald

Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Why was this remarkable? For those outside contemporary art (and, I imagine, those within), most socially oriented art projects with varying degrees of explicit politics seem awkward, if not laughable. Unlike, say, Rirkrit Tiravanija or Liam Gillick, Chan seemed willing to actually get involved in non-art spaces, but also to contribute in the ways he knew how (teaching art history at universities that had lost professors during Katrina), while supporting other sorts of activist work with money, time, and attention. As this went on, he set about producing a play; not an occasion of acting and performance presented as contemporary art, but a play taken honestly and earnestly as a play. This willingness to compartmentalize and not subsume everything under the category of art made Chan an unusual figure, genuinely willing to be a node in a larger network and not simply perform this network for an art world audience—a willingness so foreign to contemporary artists that he became mythic.

He could well have been a myth. There were few images of Chan available online at the time (more images exist now, what with winning the Hugo Boss Prize). There was, and still is, a relative quietude in regard to the Hong Kong-born, Omaha-raised artist being ethnically Chinese, and that detail’s bearing on his work—a silence that, race’s importance in this context notwithstanding, is rare. Most importantly, there’s his retirement: what’s a better instance of the “Adornian inclination towards art as a sanctuary where means-end rationality is set aside” lovingly ascribed to Chan in Claire Bishop’s book Artificial Hells than quitting art—that is, the institutions, networks, and vocations that get to define art today?

This was ignorant, wishful projection at the time on my part, as I wasn’t aware of the gesture’s Duchampian overtones, what with the two decades Duchamp spent working secretly on Étant donnés while in nominal retirement. It’s odd for me to still cling to the notion of Chan actually quitting, especially since I’m writing this profile for an art magazine. Why deny Chan the capital obviously waiting for him? Why begrudge him praise, even if it is often bland and easy?

Courtesy the artist, Badlands Unlimited, and Greene Naftali, New York

Still, Chan’s relationship to writing—whether about him, by him, or through him via Badlands—warrants a second look. As for the writing about him: regardless of its historical worth, contemporary commercial art writing is a pretty debased discipline. Too much content made for too little money by too many people who equate knowing about something with being able to write about that thing. When made the object of art writing’s tendency towards maddening idiocy, Chan performs a calculated noncommunicativeness: not a Bartleby-esque refusal, but an aestheticization of language sprinkled with not-quite-of-the-moment philosophy to be gobbled up wholeheartedly in its ostensible earnestness. This is most apparent in his interviews. “How does it feel to win the Hugo Boss Prize—what does it mean to you as an artist?” asked Mandalena Munkonge, a reporter for Dazed, to which Chan replies:

It means and feels something like this.

A \ / //o\ beautiful thing

| .-’-. |

_|_______ — / \ — ______|__

`~^~^~^~^~^~^~^~^~^~^~^~`

is an indeterminate figuration

-. / \ —

`~~^~^~^~^~^~^~^~^~^-=======-

~^~^~^~~^~^~^~^~^~^~^~`

`~^_~^~^~-~^_~^~^_~-= made

reasonable

by feeling. =====

This reads as a fine aphoristic summation of Kant on beauty, placed in what typical art writing might call a disruptive take on the emoticon-writing that characterizes our digital exchanges. This is something Chan does a lot, which seems mostly for his own pleasure and to the edification of no one—but also to the consternation of no one, as older people are happy to have their Kant livened up with a little new media and younger folks rejoice that how we played around with text on AOL Instant Messenger in middle school could be made relevant again, let alone valorized with the addition of Kant.

Of course, Chan often writes in unbroken sentences, entire essays, even. A volume of his selected writings appeared last year to much acclaim. Part of that is due to the state of exceptionalism granted to artists’ writing by those who bother to read it. See George Baker’s introduction to the book: “Sometimes political in nature … sometimes poetic, sometimes fictional, sometimes historical—even art historical: writings by artists embrace a heteronomy that destabilizes the act of writing,” Baker tells us—as if writers themselves weren’t interested in this heteronomy, and as if this heteronomy were always a success. After this exhausting conception of artists’ writing, Baker goes on to claim that Chan’s texts “betray an engagement with philosophy of a depth rarely seen in the domain of art—perhaps never seen, on this level, before.”

PHOTO: Gil Blank

Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali

Let’s not mention Adrian Piper, who is now as much Kant scholar as artist. What is the engagement that Baker praises? According to Chan, it’s that of an amateur enthusiast: in interviews with him, including my own, he emphasizes how little formal instruction he has on these matters, while evincing a sustained interest in spite of such constraints (though not every amateur theory enthusiast knows Robert Hullot-Kentor, who translated Adorno’s Negative Dialectics and is acknowledged in Chan’s Selected Writings). Chan is unapologetically a fan of older strains of thought that have fallen by the wayside or otherwise seem cliched today, and his writing is filled with digressions on Hegel and Nietzsche, Blanchot and Paulhan—all the trappings of a leftist intellectual so common in humanities departments as to be quotidian.

But that mundanity is deflected in three ways. First, Chan operates in the art world, not in academia (though Adorno references are a bit passé in the art world too), and happily refers to his own amateurism to absolve himself of any association with staid Hegel-lovers. Second, Chan adores his high-low cultural dichotomies, making the writing titillating for elders and nonthreatening for art school students. What a cultural polyglot, we’re told, a gentle Adorno who loves Insane Clown Posse and Thomas à Kempis! Per Cortright’s essay, a Chinese man who speaks like both a black boy and a Fulbright philosophy scholar! Third, in this new world of artistic critique appropriated by corporations desperate for cultural capital and corporate-fetishizing artists who hate school with the passion of those with hundreds of thousands of dollars in student debt, an unabashed interest in these intellectual matters is a balm to the old guard of baby boomer critics, art historians, and curators who shudder, also rightfully, at invocations of speculative realism and normcore and whatever these young people prattle on about in their press releases and at their parties.

At times Chan speaks outright the fears underlying those apprehensions: critique’s death, theory’s uselessness, art’s exhaustion and indistinguishability from non-art. Take his 2009 essay “What Art Is.” Chan points out that artistic production’s current proliferation “has no bearing on what kind of power or potential it might hold,” leading one to feel that art, if not actually dead, has had something within it die. But instead of an absolute nihilism about the role of art today—which, considering the essay’s coincidence with his retirement, would have been more compelling—Chan leaves the door open: “For art to become art now, it must feel perfectly at home, nowhere.” Art can become art again; the possibility of return exists. A collective sigh is breathed.

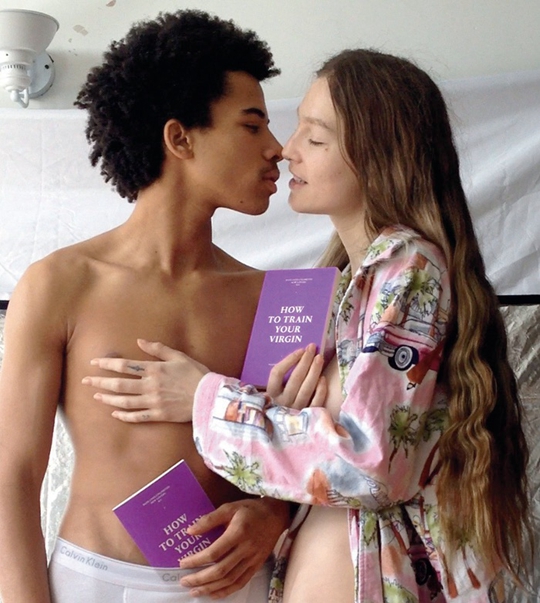

Pictured: Jasper Briggs and Alexandra Marzella

Courtesy Badlands Unlimited

A NOTE ON BADLANDS

Badlands is purposefully an afterthought here, given that it’s been the focus of most other coverage. What does Badlands mean to Chan? In the context of the show, it’s clearly a nonprojection. To hear him tell it, however, it seems to be Chan’s attempt to have a “normal” job and form a community. “It’s a shitload of work, but it’s the only day job I know that I can get where people don’t treat me as an artist,” Chan told me over the phone. “A book takes many different kinds of people to make it work, and—as I understand a community as a group of people who are different but find ways of negotiating and trusting one another enough to do something—it’s as close to community as I’m likely to get.” This struck me first as sadly sweet and then, given Chan’s “retirement” and how quickly institutions and press point to Badlands as an integral element of his artistic practice, more of the same trolling.

It’s not as if Badlands shies away from the word “art” itself. “Historical distinctions between books, files, and artworks are dissolving rapidly,” we’re told on its website—which is to say, all becomes artwork or of the art world. It then rings a little false when Chan stresses his amateur enthusiast identity with regard to publishing. “We have no right to publish these things. Who the fuck are we?” Chan said in an interview with Artnews. “But we’re doing it anyway. And we’re trying to do it in a manner we can live with, and in ways where choices are not evident or given, but we make those choices anyways, by hook or by crook. And I don’t know how else to do it.” I can’t decide whether Chan is having it both ways here, or is stymied by his reception regardless of what he does, or is acting on impulse without scrutinizing himself to this level—or, perhaps, in spite of such self-scrutiny. In any case, enthusiasm has its limits, if it doesn’t become a limit in and of itself. Chan’s own art does not seem a rewarding interest for him at this point, particularly when those with money to give and column inches to spare are effusive no matter what he does.