IT IS DIFFICULT TO TALK ABOUT MARIA’S WORK

| October 29, 2015 | Post In LEAP 35

Courtesy Carlier | Gebauer and the artist

It is difficult to talk about Maria Taniguchi’s work. Like an archaeologist piecing together artifacts, she unpacks knowledge and experience connecting material culture, technology and natural evolution. Beyond her objects, we are asked to look at their context. Who sees an object? How are we seeing this object? What associations can we make?

A lesser-known work, Untitled (Marble Lions), provides clues. Presented on a 23-centimeter portable DVD player on a wooden plinth, the video depicts two marble lions—each approximately the size of a hand, one black and one white—in front of a blue backdrop the kind weathermen hover over to stand in for virtual skies and meteorological prophecies. The cameraman stands behind the camera adjusting and readjusting the lens and lighting, sporadically appearing in front of it to iron out wrinkles in the blue material. The lens zooms in and out, pans left and right, up and down, focuses and refocuses, finds more light, too much light, less light, becomes over-saturated, readjusts, zooms out, zoom in again, and so on. The sounds of the camera pervade the video as they interpret its functions: click, click, zzzzzzoooom, zzzzzzoooom, click, click, zzzzzooooom. Often associated with power, regalia, and, in certain cultures, auspiciousness, the lion becomes small, manipulated, and emasculated through this process of dissecting, objectifying, and aestheticizing. We gaze through the camera as the lens strips the lion of meaning; over 12 minutes the process becomes increasingly absurd.

Courtesy Silverlens and the artist

In its formal simplicity, Untitled contains the irony, wit, and self-reflexivity of a good meta-joke: Taniguchi versus the digital camera, an awkward struggle between the artist and her technology. This tension is a focal point repeated in all her works, from traditional technologies to machines and computers. When the focus would seem to be on the lion, it actually frames a mise-enscène enabling us to analyze the process of the video being made. In its dry formalism, the video shifts the lens from representation to an awareness of the acts of composing, constructing, and framing, as well as the particular historical and artistic pedagogy—of gazing, objectifying, and constructing meaning—to which Taniguchi has been subject.

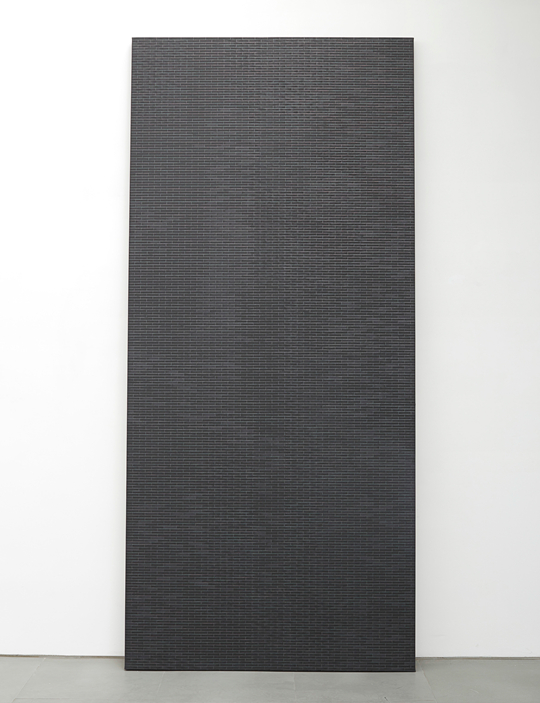

Taniguchi is best known for her monumental brick paintings, which she has painstakingly produced since 2007. Every day, she returns to the canvas, lying horizontally over the massive structure laid out on the floor, where she paints. Row by row, she labors over the stretched canvas, dipping her brush into acrylic and then water, and blackens two-by-six-centimeter cells in a grid, one after the other. The largest painting reaches 600 x 300 centimeters. Watching her work in the studio, the practice feels both transcendental and endless. She works on these paintings with regularity and rhythm, unconsciously conditioning her practice and structuring her thoughts.

Courtesy Silverlens and the artist

Taniguchi’s work can feel intimidating and impossible to decode, like a brick wall keeping people out. In an attention economy dominated by production and consumption at lightning speed, her work intervenes with different temporal registers. In a recent exhibition at Carlier Gebauer in Berlin, for instance, she presented a series of brick paintings next to stacks of posters with a grayscale image of a cave in Jordan. She invites viewers to bring along a sense of awareness. How does our perception of time change when we are confronted by monumental brick paintings marking the passage of time with such regularity, like a metronome—like breathing? And does our perception readjust when we imagine the infinitesimally slow pace at which a cave forms in the surface of the earth? She says, “Objects are not made with associations, but, within a space, associations form.” We are invited into a process by which something becomes something else. A process that, in its slow and painstaking labor, unveils a temporal space of concentration and slowing down. In a field like contemporary art that glorifies the finished product, Taniguchi encapsulates the times, speeds, and processes of transformation in her work.

In the high-definition black-and-white video Figure Study, we watch two men dig a hole in the ground with a shovel. We hear the sounds of the jungle in the background, but the men don’t exchange words. For 37 minutes, we watch them fill sacks with earth, which they carry away with them as they exit the screen at the end of the video. The viewer is unsure how much time passes between beginning and end; it could have been shot over an hour, many hours, or a few days, or it could be a repeated exercise occurring over and over again, spanning years and centuries. The image fades to black and then returns repeatedly, taunting the viewer to watch closer in case they miss something, like secrets folded in to crevices of the film. There is a sense of timelessness about the video. The two men are nondescript, and their repeated action—extracting resource from the earth, extracting resource from the earth—has no beginning and no end. In the exhibition space, the video monitor sits on one end of a wooden plinth four-and-a-half meters long. A flat piece of fired clay the same dimensions as the monitor sits on the floor at the other end.

The closer I get to Maria’s works, the more I am drawn in and clues start revealing themselves to me. Universes are contained in a single work. I start piecing together fragments: hints edited into the video, written into the title, meticulously weighed into the balance between the monitor and the slab of terracotta. Elements of the composition converse with each other like an internal logic choreographed into the piece under the genre rubric of the figure study. We are invited to study the men laboring, the slab laid horizontally on the floor, the measured composition, and each contributes its own set of cultural and historical references. These components are also part of a whole process of production—accumulating earth, firing terracotta, filming the process, and constructing them all into a complete installation—that completes the work. I look down at the terracotta slab on the floor, perhaps a reference to Carl Andre’s seminal minimalist sculpture. The installation encourages the assumption that the slab was made from the earth collected in the video, but the object also sits on the edge of the work feeling quite independent, as art history seems to exist in a silo removed from other areas of human experience.

Taniguchi’s work often involves a fetishism of form: in this case, the working man, hunched over, elbows bent, muscles tense, moving with regularity up and down, is set next to our fetishism of an object of cultural value—Carl Andre’s sculpture. While giving these forms critical consideration, Taniguchi pays homage to the historical trajectories of both these developments.

color with sound

In a more recent work, Taniguchi displays pearly white posters that appear to have been tirelessly eaten away by ter mites in a stack half a meter high. Their surfaces remind me of the holes in mechanical keycards, intentional but discreet and extremely precise. We realize that these can only be the result of a machine; no organism can create forms so perfect. We are once again confounded by two different temporal realities: the laborious lifework of a termite, which humans perceive as slow, and the laser cutting of a machine, which is inconceivably fast. Both are notions of time that can only be understood conceptually. Taniguchi’s work contains a consciousness of speed in forms and ideas, the speed of information, the speed at which objects reflect information; these elements are heightened through her compositions, and rattle against each other. Each process, form, image, or interpretation has its own internal speed. The instinct of the termite, evolved over millions of years, exists uncomfortably alongside the nanosecond it takes for the laser to produce a dozen holes. Posters are taken away by visitors to the exhibition, but the holes never get any larger or smaller; everything remains the same. Only our awareness changes.

Maria Taniguchi’s installations bring different forms and experiences of time together. Humanity’s endless extraction of resources from the earth converges with the short history of conceptual art, in Figure Study as in the brick paintings. Our collectively accumulated experiences are suggested in her careful constructions, layer by layer, in the sound, the material, the pacing, the scale, the title, the encounter, the visitor. As she told me in an interview, “It seems I have a very strong inclination for solid forms, but it doesn’t feel solid to me at all. In fact it’s really all conjectural.”

It is not that difficult to talk about Maria’s work. It just takes some time.

12 min 8 sec, 36 x 36 x 100 cm

Courtesy the artist