PROPHETS OF THE EXTREME PRESENT

| December 31, 2015 | Post In LEAP 35

In 1967, Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan published The Medium is the Massage, a slim paperback that quickly became an icon of pop-culture criticism and cemented his reputation as its high priest. A collaboration with the designer Quentin Fiore “coordinated” by Jerome Agel, the book uses bold layouts, striking graphics, and eclectic samples from art and mass media to illustrate McLuhan’s theories in both form and content—quite literally but playfully “massaging” the medium of the printed book. A pastiche of Helvetica and high-contrast black-and-white photos, Bob Dylan quotes, and New Yorker cartoons, to today’s readers it is essentially a Tumblr version of the 1960s. If it now seems dated, it is perhaps only because it was so utterly of its time—and because it has been so influential on art, design, and pop theory ever since.

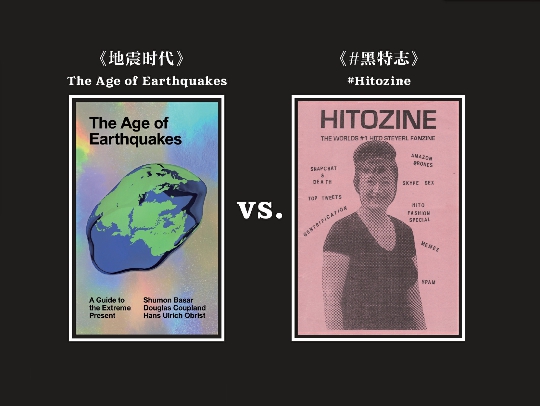

The new book The Age of Earthquakes by Douglas Coupland, Shumon Basar and Hans Ulrich Obrist seeks to update McLuhan’s classic for the post-internet age. This “guide to the extreme present” is a similar blend of deconstructed textual manifesto and arresting images (this time from some 30 contemporary artists instead of clips from Life Magazine), assembled by designer Wayne Daly in a familiar sans serif but with plenty of emoji thrown in.

While McLuhan wrote, “first we build the tools, then the tools build us,” this trio of authors proposes that the Internet hasn’t just changed the structure of our brains— it is also changing the structure of our planet. This is what gives the book its title, explained in Douglas Coupland’s glib opening hypothesis that the Japan earthquake of 2011 (and subsequent Fukushima disaster) was caused by climate change, which is in turn caused or greatly accelerated by the internet’s demands on energy usage. (As network technology uses up to 10% of the world’s electricity, this last part of the argument is exaggerated at best, and misleading at worst.) Ecology is more a metaphor for the web’s destabilizing effects on society, psychology, and time.

The book mounts an impressive collection of contemporary anxieties. Are digital devices accelerating our daily life and sense of time itself? How do we balance privacy and accountability? Does relying on prosthetic memory and cloud data change the nature of selfhood? Unfortunately, the treatment of these issues is smug, simplistic, and, maybe ironically for a retro-inspired book, dated. Statements like, “Bored people crave war / Fact” are reminiscent of mid-1990s Adbusters, the anti-capitalist yet weirdly conservative magazine that was itself a riff on McLuhanite aesthetics. In other sections, the tech analogies feel forced, like “the internet fosters the rise of the individual mind as an app… an app called ‘you.’” Overall, the writing reveals the latent grumpy-old-man-ism that has come to characterize Coupland’s work. And sometimes it just feels out of touch. One particularly tone-deaf page reads, “Rodney King was the YouTube of 1993 / If it happened today, would it be able to compete with everything else?”

This seems like a question, above all, for Hito Steyerl—one of the contemporary voices who truly seems an heir to McLuhan, and who has explored what digital technology means to the representation of politics (and the politics of representation) across her films, writing, and teaching #Hitozine is billed as “the world’s #1 Hito Steyerl Fanzine” and was created by her fans in honor of the FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) panel chaired by Steyerl at London’s Institute for Contemporary Art in spring 2015. It is a fanzine in the classic sense: cut-and-pasted essays and collages from a half-dozen contributors, photocopied and stapled (with pink paper for the cover!), and distributed informally. It includes sections like “Hito’s Best Quotes” (“Weather is water with an attitude”), selections from her Twitter, and tributes to her creative and scholarly work, as well as her fashion. There are also short visual and textual essays on topics inspired by Steyerl’s practice: Amazon drones, Snapchat, spam imagery. The design is not as sleek as Daly’s, but, as a contemporary example of form supporting content and, more importantly, context (that of the conference), the zine vernacular works perfectly.

Through its exuberance and sincerity, #Hitozine is a reminder that massaging the medium can still be refreshing and subversive, and that we probably have enough post-internet analysis from grumpy old men.