ART AS TRAVELING THEORY: CHINESE ART IN THE 1990s

| January 14, 2016 | Post In LEAP 36

A historic demarcation has been proposed at the beginning of 1990s: the modernism of the 1980s versus the postmodernism of the 1990s. As western thinking and culture flooded into the country, influenced by Foucauldian postmodernism and Edward W. Said’s postcolonial critique, Chinese intellectuals embarked on a journey of exploration into a critical thinking of their own cultures and identity.

Perhaps the exhibition “Les Magiciens de la Terre,” which took place not in the 1990s but in 1989, could be interpreted as the first open declaration of war against Eurocentrism (and an anxious attempt to challenge American supremacy in contemporary art). As curator Jean-Hubert Martin said, a large and thought-provoking exhibition was needed to review the expansion of modernism around the globe, and the new forms of art to which it gave birth. Here, pluralism remains superficial and rhetorical. The real reasons for this narrative, as Jean-Francois Lyotard pointed out, lie in the entrenched crisis of legitimacy faced by western modernism’s grand narratives, and the ensuing competition between modernism and postmodernism.

In February, 1993, an article titled “Art contemporain. Peintres ou imposteurs” was published in Le Monde des débats, depicting a major debate between advocates and skeptics of contemporary art. This was the continuation of conflict between modernism and postmodernism. Coincidentally, both sides cited China as a third party in support of their own arguments; it is imperative that modernism locate a third party in order to consolidate and extend itself. Postmodernism, on the other hand, seeks a third party to topple modernism’s agenda of self-recognition.

In the fifth century, Christians referred to themselves as moderni to differentiate themselves from early Christianity. During the Renaissance, progressive thinkers thought of themselves as belonging to the modern world. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the quarrel of the ancients and the moderns emerged in France. After the 1960s and 70s, a discussion of modernism and postmodernism swept across the postwar western world. The logic of western culture relies on a belief in the modern, based on thinking “before” and “after” outside of normal time.

To some extent, China’s modernization in the 1980s fit the western definition of a modern society fuelled by industrial production, a free market economy, and the transition towards democracy. European thinkers regarded China as an example of localized modernity, while followers of postmodernism could look to Chinese contemporary art on the deconstruction of authority, tradition, and collectivism. Over the past three decades, Chinese art has been an important piece of supporting evidence on both sides of this debate. Modernists saw what China had in common with enlightenment, reason, science, progress, rights, and subjectivity, while postmodernists saw the possibilities of deconstructing, overturning, and disintegrating discursive hegemony.

China, during this stage, was busy finding the right methods by which to pursue modernization while remaining consistent with the goals of social development since the Enlightenment. In this sense, the Chinese experience has become an Asian buttress to western modernism. Many European defenders of the Enlightenment, like Jürgen Habermas, turned their attention to Chinese praxis when they found themselves coming up short against postmodernism.

Huang Yong Ping, Gu Dexin, and Yang Jiechang, the three Chinese artists invited to “Les Magiciens de la Terre,” were thought of as China’s most progressive and independent artists. In fact, they were so progressive that they couldn’t be put into any category. They met the organizers’ expectations of global artists: their work embodied both universal values and unique individual styles, while not representing any one nation or ethnicity. Exhibitions such as “Les Magiciens de la Terre” are interpreted in the context of postcolonialism. Some researchers even claim that the exhibition symbolized the end of western hegemony in modernity and its entire system of ideology, aesthetics, and institutions.

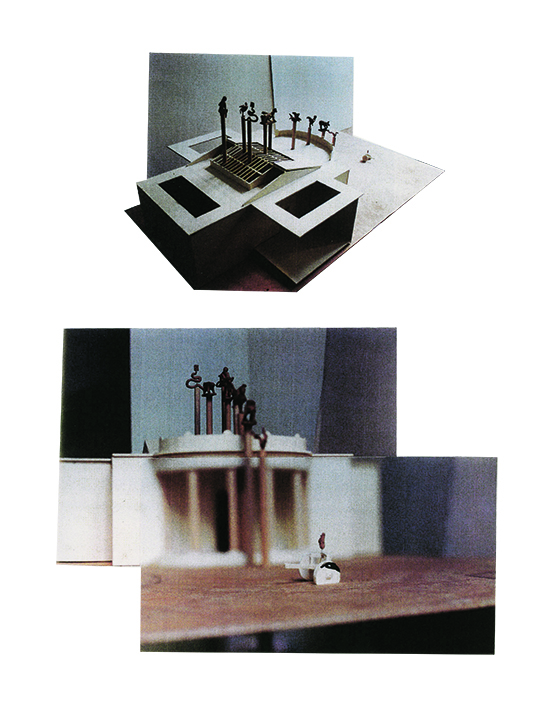

More international exhibitions of Chinese contemporary art were organized following “Les Magiciens de la Terre,” most prominently including “Chine Demain pour Hier,” funded by the French Ministry of Culture and curated by Fei Dawei in 1990; “Exceptional Passage,” in Fukuoka, also curated by Fei; “China Avant-Garde” at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, in 1993; the 1994 São Paulo Biennial, the 1993, 1995, 1997, and 1999 editions of the Venice Biennale; “Silent Energy,” curated by David Elliot at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford; and “China!” at Kunstmuseum Bonn in 1996.

“China Avant-Garde,” curated by Jochen Noth, Andreas Schmid, and Hans van Dijk at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, was, in fact, more than just an introduction of contemporary art. It covered the entire avant-garde cultural phenomenon in mainland China from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, including the latest literature, theater, film, contemporary art, and rock music. The exhibition managed to make a greater contribution to enriching the literature of the field than “Les Magiciens de la Terre,” yet it failed to pose any question or challenge to western contemporary art. In fact, what the exhibition revealed to the world was China’s stumbling attempts at modernization since the late 1970s.

What was most intriguing about the 1990s Chinese contemporary art exhibitions in the West was the presence of Chinese authorities. Through their belated participation, one could feel a sense of the country’s official ideology—grand diplomatic public- ity. Although some of the artists selected by Chinese authorities for the Venice Biennale in 1997 were the official representatives of modern Chinese culture, they were—rather awkwardly—generally considered to be seriously out of touch with international contemporary art.

In 1999 and 2001, Harald Szeemann curated two consecutive editions of the Venice Biennale. He began to select entries that worked against the standard of western contemporary art. Of all the participating artists, he directly invited some 20 percent, but a starry cast of Chinese figures did not induce much response from the art community in the west. Interestingly, a series of articles analyzing China’s social changes through art in the Biennale appeared on the cultural pages of Italian newspapers. After 2003, when the Chinese Pavilion officially became a member of the Venice Biennale, China’s ambition grew more evident.

Some exhibitions presented themselves as personal narratives, with prominent features of pop art, but in fact continued to offer difference as a model for consumption: “Jiangnan: Modern and Contemporary Art from South of the Yangtze,” curated by Zhang Qing in Vancouver in 1998; “Transience: Chinese Experimental Art at the End of the Twentieth Century,” curated by Wu Hung; and “Inside Out: New Chinese Art,” curated by Gao Minglu.

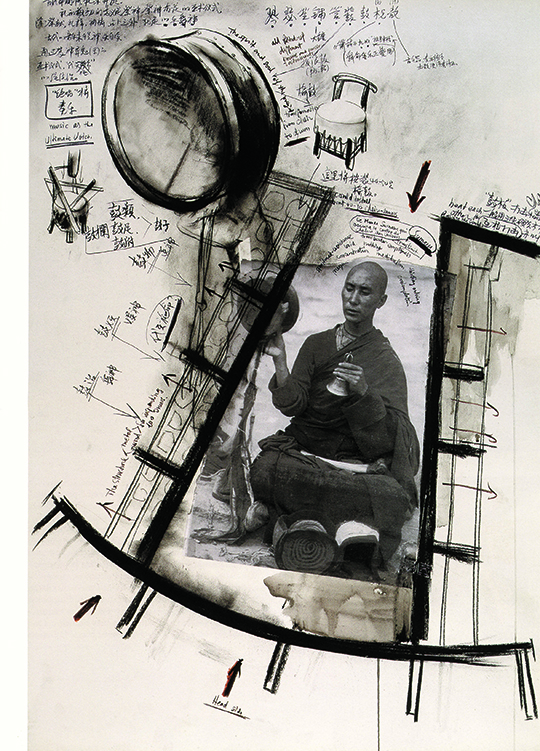

Chinese contemporary art—abroad in the 1990s—often fought exoticism with alienation and vulgarity with obscurity, while it pursued of liberation on its own terms in material and concept. Contemporary art tried to deconstruct the various logics applied to it with the methodologies of pop art, breaking the boundaries between art and life in order to de-subjectivize and decentralize the aesthetic subject. These features won the appreciation of postmodernist followers, but the pursuit of subjectivity, built on the foundation of cultural identity and group consensus, made modernists feel that they, too, had found new allies. It was with the identity of a third party that Chinese contemporary art made a bizarre appearance on the radar of western modernity. It also lent ground to Edward Said’s notion of “traveling theory,” which holds that, when theories or worldviews travel outside their points of origin, their meanings are often altered and they are highly likely to be abused for purposes not even remotely resembling the original intentions of their authors.

On a more profound level, the evolution of modernist thinking in the west provides the context for the attention received by Chinese contemporary art during the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s. After coming into contact with Chinese contemporary art, Europe realized that many long-forgotten topics in the west were still enjoying their heyday in China. On top of this, the localized modernity practiced in China served as a mirror of western modernity, invoking reflection in the west. As the rivalry between modernism and postmodernism subsides in the twenty- first century, however, the existence of Chinese contemporary art as a third party is no longer significant. Perhaps this will be more conducive to the return of Chinese contemporary art to art itself. (Translated by Rachel Huang)