Samson Young: Composing at a Distance

| March 23, 2016 | Post In LEAP 37

Samson Young is a genre artist: everything he does builds on his training as a composer, an approach that is increasingly rare in the multi-disciplinary art world of today. Young is also a rare example of success in the notoriously challenging crossover between experimental music, sound art, and contemporary art. This past year, 2015, has been his breakout moment, both in terms of validation (he won the BMW Art Journey for his presentation at Art Basel in Hong Kong, and just closed his first New York solo exhibition with Team Gallery) and in terms of rigor. The projects showcased in these venues are, from a critical standpoint, his best yet, putting aside some of the technical wonkiness of his background as a music geek (an iPhone orchestra, for instance) in favor of using composition as a tool with which to break down historical and everyday structures of power.

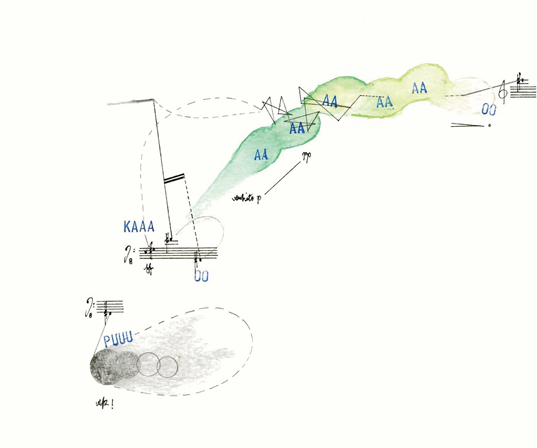

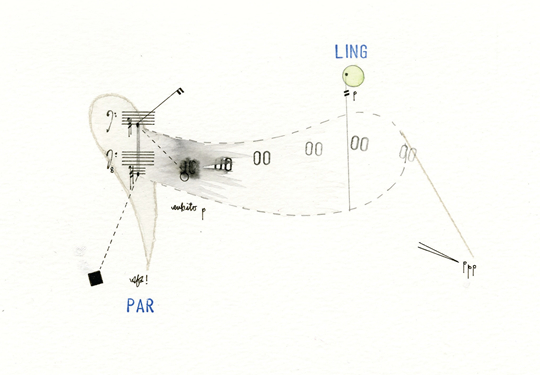

Pencil, ink, watercolor, and modeling paste on paper, 20 x 29 cm

Studies for Pastoral Music, (Colt Walker Revolver 0.44 Caliber), 2015

Pencil, ink, watercolor, and modeling paste on paper, 20 x 29 cm

The centerpiece of this transformation, Nocturne (2015), reflects the complex new politics at the heart of Young’s new directions. For this project, which won the BMW prize and was then repeated as a more durational piece for a later gallery exhibition, the artist set up a pirate radio station around a foley stage on which he creates a live soundtrack for found video footage. This footage, culled from publicly available reportage online, consists of aerial photography of night bombings and other military attacks, primarily in the Middle East and generally tied to ongoing tumult in Iraq, Syria, and Palestine. Young’s addition serves to diminish the distance between the action on the ground and the spectacular nature of media spectatorship. His interest in drone warfare, a viewer might suspect, could be half with its violence and half with its technological alienation; Young constructs a humanist politics of engagement through both sides of the media.

Pencil, ink, watercolor, and modeling paste on paper, 20 x 29 cm

This approach to violence and its media simulation is expanded upon in “Studies” (2015-ongoing), a series of drawings in which Young borrows from the graphical language of musical notation in order to illustrate the sounds of what he describes as “historical firearms.” One might read these as instructions for his foley work, or perhaps as after-the-fact sketches of these performances, but it is more interesting to imagine them as completely unrelated entries in the same series—this one could be a Revolutionary War cannon, and this one a cavalry charge from the Battle of Mohács. They function as ample paratexts that reinforce and diversify Young’s live performance, and their stark formal beauty delivers a new angle on Nocturne: perhaps it, too, could be beautiful.

Pencil, ink, watercolor, and modeling paste on paper, 20 x 29 cm

Young’s penchant for historical research reemerges again in Pastoral Music (But It Is Entirely Hollow), a site-specific performance expected to take years to complete. He is spending time visiting World War II-era structures in the New Territories, Hong Kong’s rural northern district, along the Gin Drinker’s Line, a British defense plan that failed magnificently during the Japanese invasion of the city. In each one, he sings and records a Cantonese nursery rhyme. The project is rounded out by more annotations along the lines of “Studies,” which draw on the geography of the defense line as if it were successfully implemented today. This, perhaps, marks Young’s most direct political statement; who, after all, might be invading Hong Kong from the north today? His new form of practice balances on a stunningly fine line between an intimate engagement with dry or distant historical matter and an intentionally distancing relationship with the difficult politics of the present. This range of strategies allows Young to mask himself as a composer even as he pulls the contemporary art system closer to the contexts with which he is familiar.

Text by Robin Peckham