Painting after Reflection Theory: Some Artists from Shenyang

| May 23, 2016 | Post In 2016年4月号

Shenyang, a representative industrial city built during the socialist era, is one of eight Chinese cities with a major art institute. The pace of life is relatively slow, the pressures of daily life relatively light, and, even if the city is, in many respects, somewhat backwards compared to first tier cities, it is not particularly isolated. For these reasons, a group of young artists who grew up in Liaoning Province or graduated from Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts choose to live and work in Shenyang. There, artists including Song Yuanyuan, Bi Jianye, Fu Jingshi, Geng Yini, and Huang Liang preserve the independence of their artistic practices.

Is this the result of a romantic obsession with the concept of independence? It could be said that they share certain obvious points in common. They depict specific objects in order to reflect on the language of depiction itself. This introspective property gives their painting a metaphysical quality, addressing questions within painting. They work in representational painting that seeks to express what cannot be expressed. So, could this independence be seen as a form of self-isolation? Is this inward-facing quality also a kind of active retreat from contemporary reality? If even the recollection of and sentimentality for repetitive, tautological painting ideologies like Socialist Realism have lost their foundation, then, faced with specific realities, do these paintings lack the appropriate consideration of contemporary visual culture? Are they passive in their resignation to the status quo? Or do they rediscover the potential of painting within the current media context?

Different viewpoints will yield different answers. We should first look at what has shaped the particularities of the style known as Northeastern Painting. The terms of isolationism and retreat are insufficient; the school’s introspection actually derives from its moral angst.

Adorno said, “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” In the past 20 years, Shenyang artists have witnessed the closure of state-owned enterprises, the resulting layoffs, the decline of culture, and the economic recession. For many, this has had an influence on their art that is impossible to ignore. But, when it comes to the younger generation of Shenyang artists, it has long been clear that what they are looking for is not a return to a mechanistic theory of representation. Instead, the aesthetic and ethical dimension is deeper: there is a conflict between beauty and their current reality, which is in no way beautiful. Introspective artists, by contrast, maintain a close connection with their specific realities.

In general, artists who think like this do not tend to choose painting, and certainly not representational painting, a medium that has a long history as a language of expression and in which aesthetic tendencies are firmly ingrained. Artists may be more inclined to use a completely new medium for their reflections. But these Shenyang artists are both attached to the medium of painting and also want to, as Poussin described Caravaggio’s work, destroy it—so long as they continue painting, the reflection is destined to remain incomplete. This gives their painting an extremely complex ideological and spiritual density, but does their use of painting also force them into a relatively narrow path? If their reflections on the language of painting use only painting itself, are they cocooning themselves away from the world?

Again we return to the paintings. It’s impossible to overlook the influence of Wang Xingwei on this generation of Shenyang painters. In many paintings that have become intertwined with art history, he replaces various elements on the level of the symbol, creating barriers in the direct progression of painting towards the depiction reality. By suspending his paintings between different levels of reality, he deconstructs reality and enters into discussions of painting prior its aesthetic dimension.

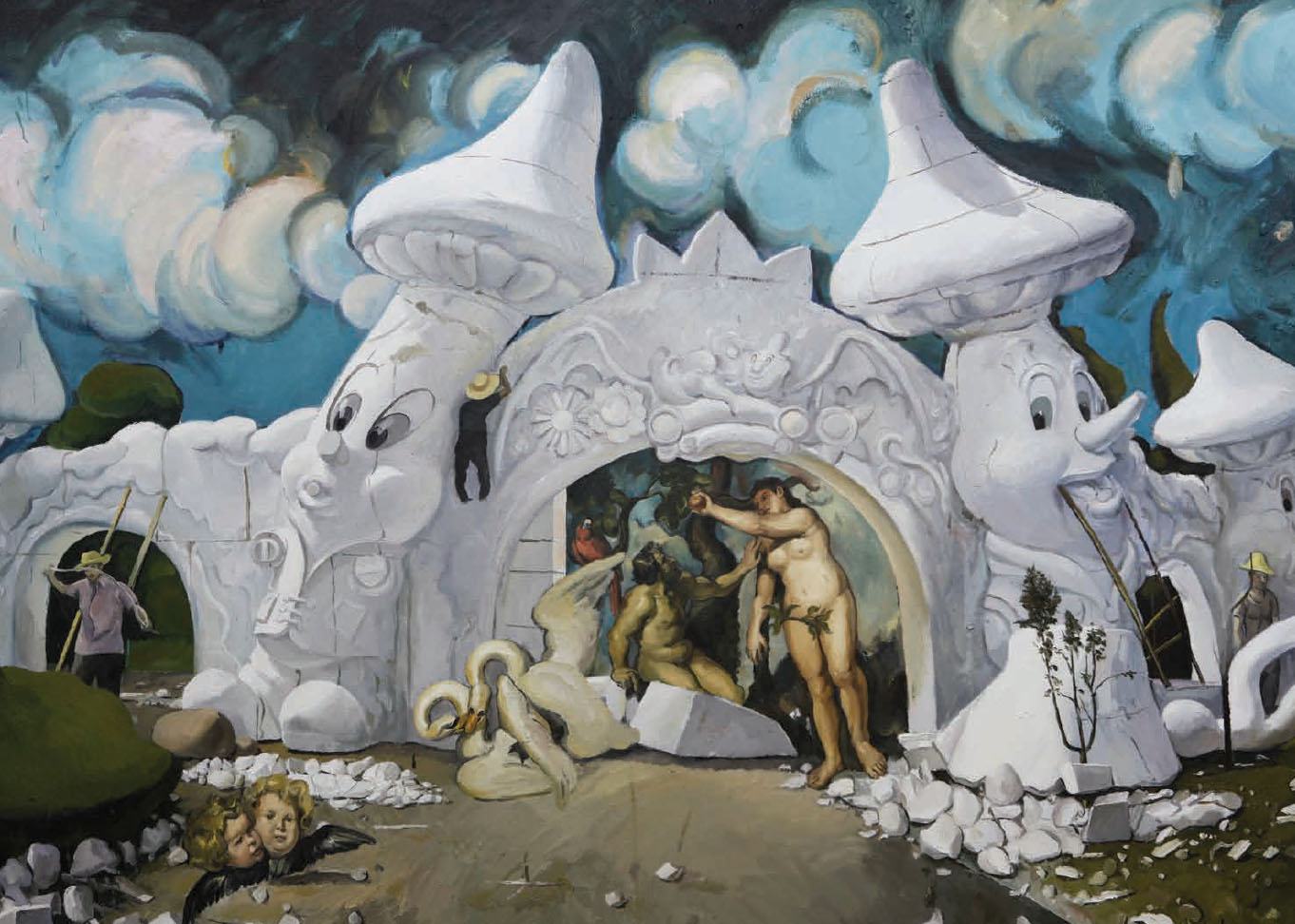

In the younger generation, Song Yuanyuan’s paintings are similarly suspended between different layers of signs, and are also suspended between different layers of reality. Which version of reality comes firsthand reality? Which is secondhand? You are in me, I am in you, and neither can be distinguished. There is no longer a clear boundary between true and false. Song, however, is not satisfied with deconstruction. Instead, he uses the compositional methods of classical painting to organize figures on the canvas. The figures that he adopts from classical painting appear in the cheap counterfeits often sold on the market, or figures that don’t enter the painting. At first glance, the placement of these figures, the figures themselves, and the actions they undertake resemble the world-shaping heroes of epic tragedies from classical painting. But, in fact, they cannot undertake these actions in the world. By this roundabout path, Song responds to the reality of Shenyang’s decline.

In Song’s words, if this reality touches him and becomes a part of the reality he experiences every day, why wouldn’t he express it? Expressing Shenyang with industrial decline has become a symbol, but current developments in the language of painting allow it to do more than simply reflect this fact; there are more possibilities for facing the issue. Song’s shifting use of reality exists within this framework, just as the works themselves are mounted in the cheapest Baroque frames from Shenyang’s Ninth Road wholesale furniture market.

In contrast to Wang and Song, who manipulate or simulate painted space within the tradition of painting, there exists in the younger generation a tendency to enter the painting from the opposite direction: to resist painted space. The discourse of the painting system often dictates the location of an object in painted space. When placed in this given location, the object is no longer itself. Instead, it becomes a part of the painting. The work of the younger generation of artists frees these objects, allowing them to separate themselves from the preconceived notions of painting discourse.

For example, the objects in Huang Liang’s paintings often appear to have the power to warp spatial perspective. He expresses the irreducibility of spirit and matter in a three-dimensional space, suggesting the spiritual power that is externalized there. Many of Fu Jingyan’s works have a monochromatic background, and the delicate brush strokes that compose this background have a certain relationship to the forms in the painting. This relationship often derives from other fields (the relationships of magnetic fields in physics, for instance), and does not originate in painterly relationships. This undoubtedly creates a bizarre feeling among the forms in the painting. He emphasizes a response to, not a reflection of, reality. Responding to reality demands the rejection of prior grammars and styles, including those in his own works. Huang refuses to settle on a particular painting style and maintains wariness of tendencies towards systematic work, hoping to remain in an active position.

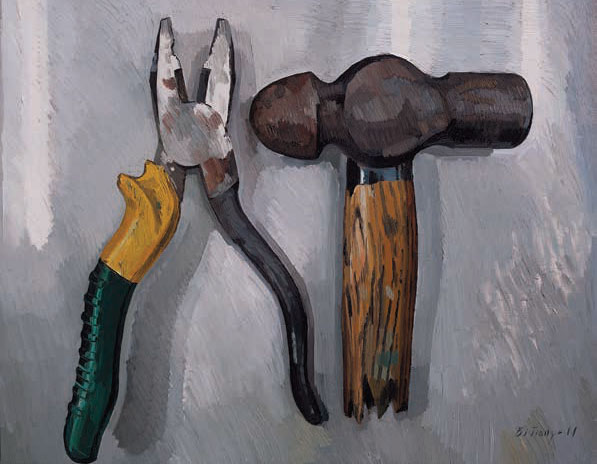

In Bi Jianye’s work Tools, the canvas is empty save for the tools depicted. The context for the tools has disappeared, creating a certain absurdity. In contrast to objects in paintings, there are no inherent requirements for the tools we use in daily life. Objects do not care whether they are remarkable or classical or of the most common, ordinary variety. In the brief title Tools, Bi faces a decision: Do I need to present tools, or do I first need to recognize that painting is not a presentation of tools but a representation founded on their presentation? Even if Bi uses the most exemplary painting techniques to depict the commonality of the tools, the final work will enter the exhibition space as a painting. Whatever the artist decides, this remains the case. Is this not a metaphor for the exploration of painting itself? A closed loop in which the farthest point remains unknown. Consequently, the most important item may not, after all, be whether one explores the boundaries of painting. Instead, it is whether he or she chooses to break the boundaries and exceed painting, or reaffirm those boundaries with new methods and perspectives.

Today, film and photography serve as media for both art and the exchange of daily information. In comparison, painting is only an artistic medium. It appears only in studios, exhibitions, and storage facilities. In what sense does art still shape society, or in what sense is it relevant to the visual shape of society? Is painting today simply a commemorative product for elite society? Because all people can write, perhaps we could say that only the activity of writing is now a democratic method. How can we think of painting in response to this formulation? This is a formidable question. We may as well change our viewpoint: if writing is democratic, that is not to say there is democracy between writers, but that the relationship between words and subjects is democratic. Meaningful writing today indicates the truth of words that have been stigmatized, addresses their stigmatization, and allows them to be spoken instead of avoided, all while exploring new words and subjects for writing. Seen this way, do the paintings of the Shenyang artists described here measure up? Consider, for example, Huang Liang’s renewed attempt to make contact with Soviet-school oil painting techniques that were stigmatized by Socialist Realism and Song Yuanyuan’s attempt at a renewed contact with the symbolic conscious of Shenyang’s industrial society. Perhaps we could see their painting practices as a renewed collection of the modes of discussion which existed before ideological pollution. If any two images are already in discussion, they use a complex language to recode themselves, permeating their latent mutual awareness and creating barriers. Through clandestine forms like these, artists shape society.

(Translated by Orion Martin)