THE PARADOX OF EXHIBITION

| January 4, 2017 | Post In LEAP 42

DADA CANNOT BE EASILY ACCEPTED,

NOR EASILY REJECTED.

IT RECALLS THE WORDS OF THE “DADA MANIFESTO”:

“… THAT’S IT. BUT OF COURSE…

IT’S A QUESTION OF CONNECTIONS, AND OF

LOOSENING THEM UP A BIT TO START WITH…

I WANT THE WORD WHERE IT ENDS AND BEGINS.”

However, if we begin with a standpoint, thought and action often risk drifting away from reality. Expressions that appear similar linguistically can yield great disparities due to changes in the perceptual methods between different eras. It is necessary, therefore, in every moment to constantly be investigating what changes are produced by the technical conditions that linguistic expression relies on, and how differing methods in the past influenced the perceptions of people.

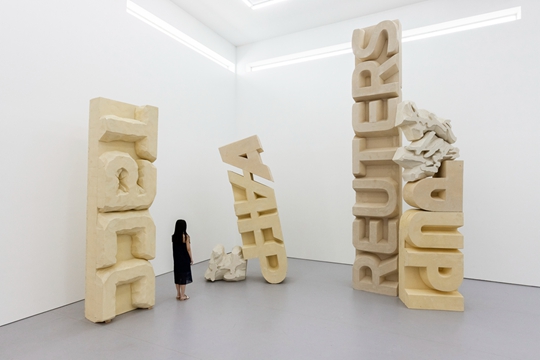

Courtesy Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong and the artist

The 1920s and 30s vibrantly displayed the technical means of dissemination, including the printing press, camera, and television emphasized in Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” John Heartfield used photographic collage and published a great number of anti-Nazi montages in newspapers as propaganda posters and illustrations. Still, he was not listed in the Nazi criticism of “degenerate art.” In “Judge for Yourselves!” – The Degenerate Art Exhibition as Political Spectacle, academic Neil Levi analyzes an interesting phenomenon:

First, the development of technologies for mechanical reproduction intensified disenchantment with the worship of art’s aura. The avant-garde at the time also questioned and criticized the investment of institutional power into the art museum as the receptacle of that which is sacred in art. They hoped to mystify artistic practice, and, of course, the works of the avant-garde received significant support from emerging exhibitions. With the “Degenerate Art” exhibition, the Nazis sought to destroy the power that the avant-garde had already attained through the contemporary art system. Therefore, Heartfield, who used the media as his exhibition method, naturally fell outside the scope of the Nazi targets.

Dimensions variable

Second, the aesthetic appeals in the “Degenerate Art” exhibition, particularly those of expressionist works, sought to break from a realism that depended on the audience’s retinal experiences. Nazism, in contrast, required the unimpeded transmission of visual information for ideological propaganda and supported realist image making. Once again, Heartfield’s aesthetic appeal was separate from the expressionist works that the Nazis focused their attacks on, because in order for his photographic montages to become powerful anti-Nazi propaganda, they too had to be easily and directly read.

The Nazis wanted to use new methods in the media to replace a previously established image experience—dependent on exhibition spaces—with a new, self-service artistic aura. While the Dadaist Heartfield insisted on publishing in the media, thereby opposing a return to value worship within the exhibition structure, at the same time he did not give himself over to complete disenchantment. Rather, he used new methods of dissemination and exhibition to counter Nazism.

Heartfield’s work appears completely different from the difficult-to-decipher works of Zurich Dadaists, and his methods are similarly at odds with current contemporary art practices. But so long as the “detachment” in the spirit of Dada is not understood in a doctrinal or negative sense (Dada does not mean negating actions, nor suspending goals), then we can still see the unpretentious practices, which the era struggled to define clearly or classify, both as a response to the Dada Manifesto of 1916 and as connected to the aesthetic states many Chinese contemporary artists incorporate into their practices today.

“… That’s it. But of course… It’s a question of connections, and of loosening them up a bit to start with… I want the word where it ends and begins.”

(Translated by Orion Martin)