Seven Days of Ghost Sightings

| August 30, 2021

Day One

No one would have imagined that the Residents’ Committee Chairman would be the one to discover the ghost. It sat there for days, motionless, while everyone from the Committee gave it a wide berth, careful not to step on it. But that’s what ghosts are like, always materializing in unforeseeable ways and taking on unpredictable forms. This one was no exception. There it was, right beside you, clearly visible, but for whatever reason, you had no idea it was a ghost—until the day it disappeared.

The ghost disappeared on a beautiful sunny day. The Residents’ Committee Chairman was just about to place his foot in the region once occupied by the ghost when he noticed it was gone. The moment of revelation was followed by a series of events—a sudden stumble, a period of unconsciousness, a broken coccyx, a discharge from the hospital, and finally a return to the scene of the crime with the Deputy Chairman to investigate the matter of the ghost.

“The ghost was right here?!” the Deputy Chairman said, pointing at a depression in the floor.

“Yes,” the Chairman replied. “Then it disappeared.”

Two months after the Deputy Chairman took over as Chairman, Shanghai entered its long rainy season. It was only then that the new Chairman realized that his predecessor had not gone mad. Sure enough, a pool of water had formed in the same spot on the floor. When a banana peel was dropped on its surface, it was as if the ghost was smiling.

Day Two

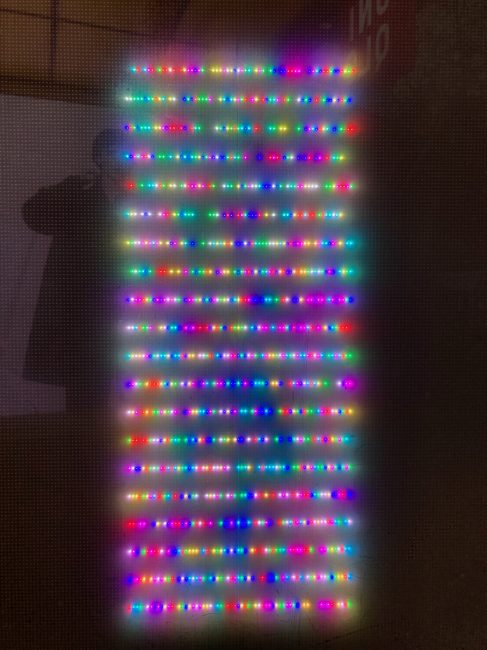

Until yesterday evening, this was the brightest street corner in Shanghai. By the entrances of all the branded fast-moving consumer-goods stores were huge screens submitting passersby to an onslaught of light, commandeering this part of the city and transforming it by night into a protectorate of the luminous nation of commerce.

But today the screen that faced south had decided to display a poem in protest against consumerism. It was much longer than a sonnet, some 50 or 60 lines in total, in which each word was one of many colored diodes that combined to express a codified digital sentiment that was yet to be deciphered—and perhaps had no need to be: a flash of life from a lifeless advertising board in its dying moments.

“What sorcery is this?” the technician said as he restarted the screen for the second time, only to get the same result. Actually, if they’d been paying closer attention, if they had thought to look at the subtle differences on the screen each time they turned it on again, they might have noticed that the poem was changing slightly. The length and rhythm of each line were the same, but every word, which is to say the color of every pixel, was different. It was as if the screen’s dysfunction came with formal constraints, which the machine had learned and was exploiting to compose brand-new poetry.

Day Three

Ma Sheng was convinced that you could not see a ghost twice in one day.

Moreover, it was a beautiful sunny day, with an immaculate blue sky and the cherry blossoms in bloom; but on the podcast he was listening to as he drove his car someone was telling a ghost story. The storyteller spoke Mandarin in a strong Cantonese accent, and almost every word was pronounced incorrectly. But in the broader context of the story it wasn’t difficult for Ma Sheng to make the necessary adjustments to the pronunciation in his head: “whizz” was supposed to be “was” and “will” whizz really “wall”… The subtle mental work of this series of unconscious aural revisions had an anaesthetizing effect on Ma Sheng, lulling him into a state of pleasant calm, which meant that when in the story the protagonist’s reverse-parking sensor started beeping despite there being nothing in the rearview mirror, it shocked Ma Sheng more than it would have done otherwise.

It was at this moment that Ma Sheng turned his car down a shaded, tree-lined road and noticed something strange. The street on Google Maps was marked red, meaning it was very congested, but in the real world the expansive road before him was almost deserted. There was not a car in sight. Ma Sheng, who was still frightened by the story he had just heard, lowered his speed and, with trepidation, inched forward for a few dozen meters or so. But the street was still red on Google Maps. Just like the ghost story’s protagonist, Ma Sheng began muttering, “Please God, please God,” but the street on Google Maps remained red. He felt his face turn the color of the street on his phone. “If there really are ghosts here, the last thing I want to do is hit one of them,” he thought innocently to himself, and so he decided to pull up at the side of the road and have a cigarette to calm his nerves. A man who looked like he might be German walked past dragging a huge suitcase behind him. “Sure is quiet today,” Ma Sheng said, not knowing why he suddenly started talking to this German in a Beijing accent. It turned out the German could speak Chinese, but what he said caused Ma Sheng to lean back on the bonnet of his car for support:

“The traffic’s terrible though.”

Ma Sheng didn’t see the article that came out a month later on the work of German artist Simon Weckert. He never found out that the artist’s suitcase was filled with smartphones, all connected to Google Maps.

Day Four

The real-estate agent must have hated her. Or maybe it’s some weird prank the estate agent and landlord liked to play? Who knows. Either way, this is the story of what happened. To this day it chills her to think about it.

Wouldn’t everyone have done the same in her position? In her defense, that’s what finding a place to rent’s all about. At the end of the day you want a good area, a cheap price, a decent flat, with a full set of furniture, not too ugly, that’s near where you work, on a street with good amenities… But each place she saw came with a bunch of “buts”. In hindsight, she thought, the estate agent must have eventually lost patience with her.

When they went to see the house that was “certain to satisfy all of your requirements,” it was a beautiful sunny day. She sat on the back of the real-estate agent’s electric scooter as it entered the street, which was right in the city center, and pulled up at the side of a three-story detached house at around noon. “The whole building for only 2,000 a month.” Later, when she recalled the estate agent’s words, it occurred to her that there was something provocative about the way he said it.

An old man opened the door. His white curly beard resembled the lines of a sketch drawing enclosing a broad face that bore few traces of hardship. Even his eyebrows were curly. The estate agent told her that this man was the landlord. “So then,” the old man said after he had shown her around the house, “do you think you’d like to live here?” “Is it really only 2,000 a month?” she asked hesitantly, not quite believing her good fortune. “Of course. Why would I lie to you? It’s just…” The old man paused, as if there was something he had yet to tell her. “It’s just what?” she asked. “It’s just… I’ll be honest with you. There’s a ghost in this house,” the old man said calmly, his eyes fixed intently on his potential tenant.

“No way! What ghost?” she answered almost instinctively.

“You.” This was the last word she heard before she fainted.

Day Five

“Sometimes Ghosts Appear on Sunny Days” opens with a quote from the critic Leung Man-tao: “It’s not ghosts people are afraid of, but the dark.” Despite this, all the pictures in the photography book are taken on sunny days. “We must learn to understand the dark from a metaphorical perspective,” the photographer writes in the afterword.

A series of utterly ordinary things – a bulge on the trunk of a wutong tree, rubber gloves hanging from the handlebar of an electric scooter, a waterproof jacket on a washing line, some ethereal glimmers on the fencing around a construction site—that nonetheless inspire a certain uncanny feeling inside us. Does the concept of the “uncanny valley” explain this reaction? Or is it that these images act like a mirror, drawing out the darkness hidden within us?

Day Six

“Warning: you are entering a state of sleep-deprived driving. Warning, you are entering a state of sleep-deprived driving…” Whether it was the effect of the masks covering our faces or the warmth of the light on that sunny day, none of the passengers felt much like talking and the bus was peculiarly quiet, which meant that the sudden arrival of this automated interjection—tirelessly repeating every few seconds in the same neutral and impassive tone of voice as it made its objective assessment—hovered in the air in bold typeface and with a sense of urgency, implying that someone somewhere ought to be doing something.

Although the statement was directed at the second-person singular—as opposed to declaring, “He is entering a state of sleep-deprived driving”—all the passengers turned to look at the driver, a slightly balding middle-aged man whose gaze remained fixed on the road ahead of him as if nothing had changed, exhibiting no sign of someone who might be deemed “sleep-deprived,” against whom even an accusation of inattentiveness would have seemed unwarranted. However, the voice continued its pronouncement unperturbed, as though it possessed information of which we had no knowledge and that granted it the authority to pass such resolute judgments and to warn passengers of the situation. Or perhaps it was an expression of sympathy with workers?

In striking contrast to the driver’s indifference—or was it composure?—an old woman who was getting ready to get off the bus decided to take the initiative and say something: “Dunno about you, but that noise is driving me up the wall!” She seemed to be directing her words to the driver but by the time the bus doors had opened and she had made her way indignantly off the bus the driver had not provided her with what she wanted—a response that signified a shared understanding, a conspiratorial smile perhaps—and instead had continued in his state of indifference or composure as though he had accepted the accusation or assessment that he was “entering a state of sleep-deprived driving.” Or perhaps he had come to terms with the absurdity of the accusation or assessment such that he saw no need to rise to the occasion of formulating a response.

After all, the bus had to go on.

Day Seven

These stories are even better than last year’s! Are you still buying them off the internet?

Yes! But…

But what? You’d have to be possessed to think you could’ve written them yourself.

But it’s not a ghostwriter this time. It’s AW!

A double what now?

AW, Artificial Writer. A computer program. A machine-learning algorithm that has studied writing for tens of thousands of hours!

Sounds high-tech. What did it learn from? “Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio”? “Frankenstein”? The Trump autobiography? Lu Pingyuan?

I think that’s a company secret. But look at the results! They’re pretty good!

You’re not wrong there. But you should be careful. I heard AI can be like the old vending-machine man.

Come again?

It looks like an ordinary vending machine, but there’s an old man inside who takes your money and hands out a can of coke. Everyone thinks it’s high-tech but really there’s an old man working away inside!

Does he not suffocate in there?

It’s a metaphor! Is it expensive, this AW?

It’s alright. I got a discount because I saw what one chapter was based on. The “Day Four” one. It was adapted from a passage in Enrique Vila-Matas’s “Because She Didn’t Ask”. It was World Consumer Rights Day, so I called up customer services. The AW promise is that the algorithm must “digest then create.” It can’t just modify an already existing work. So they gave me that chapter for free. Came to 17 percent off.

“Digest”… There’s something spooky about that word, like the AW’s eating enoki mushrooms or something.

Well anyway, it’s done! There’s no point hunting for bogeymen now. Even if I’d written it myself it would be like it magically appeared. That’s how art works! It’d be boring if you knew all the processes going on behind the scenes.

Well said! You’re right! It’s a clever little devil!

Images courtesy btr

Translated from the Chinese by Stephen Nashef