Undercurrents

| 2022年02月15日

Diversity, in many ways, should be recognized as the word of the decade. At least since the pandemic started, curators, artists, and other cultural agents turn over the same question from time to time: how can we diversify old-fashioned discourses about exhibition-making amongst unpredictable lockdowns, shifting border policies, and the increasingly unavoidable use of digital devices to cope with the current conjuncture? Our interview to Juaniko Moreno and Chen Tianqi stretched from the beginning to the end of summer. During this time, one of us had come halfway across the planet for a curatorial residency in Seoul, but had to return prematurely to Bogotá due to the surging Delta variant. In our first-ever Zoom meeting, Juaniko was in the Caucasus, participating in a program which decided its convening location based on which country had the most laid-back border policies. The two Chinese, who by all standards had the best chances of meeting in person, have had no luck partly due to the National Games being held in Xi’an. Ironically, these irritations in the work process speak to some of the very characteristics that lay at the heart of the exhibition that drew us together.

“Tecnodiversidad” is an online exhibition curated by Juaniko Moreno (Colombia) and Chen Tianqi (China). It is the first digital-based project awarded by the District Institute for the Arts of Bogotá, IDARTES (Instituto Distrital de las Artes), and makes use of the concept of techno-diversity as a genesis to discuss and compare both macro and micro phenomena concerning technology in Chinese and Colombian lived experiences.

Welcome page of “Tecnodiversidad”, web page screenshot.

Courtesy the artist

Curating based on concepts is a difficult task, not only in the technical sense in terms of understanding, developing and articulating complex arguments, but also in an emotional sense, as it is extra easy to fall out of favor with all parties the curator was supposed to cushion. Audiences, both general and professional, tend to find the writings overwhelming and obscure, featured artists may feel overshadowed by the overarching theories, and the theorists from whom the projects stem often see glaring misinterpretations. Tecnodiversidad’s word count easily overwhelms most walk-in audience members. The four curatorial essays average 4133 words and 49 footnotes each, in addition to the “regular” textual content surrounding artists and artworks. But in our conversations between four young curators, the text volume seems to have become a tacitly indulged guilty pleasure. After all, despite the popularity of the phrase “research-based curating,” the fact remains that independent curators (the majority of whom lack an institution generous enough to fund luxurious catalogs) are constantly missing a stable and roomy space to publish full-length research. Despite the circumstances which gave rise to the sudden popularity of online exhibitions, it does make an excellent loophole where textual work of independent curators could be published. This is therefore an essay based on empathy, on the slightly hubristic idea that it takes one to know one.

§

The concept of “Tecnodiversidad” starts from a set of parameters that have proliferated since the publication of philosopher Yuk Hui’s massively influential book, The Question Concerning Technology in China (2016). The terms and proposals in the book have since raised widespread interest in the culture and art circles, in China particularly, where the philosopher has lectured and keynote presented at various institutions, including the China Academy of Art’s Institute of Network Society, where both curators of Tecnodiversidad had studied. Summarizing Hui’s concepts is not our task in this writing, nor was it Moreno and Chen’s ambition as curators whose project had largely been inspired by said concepts. As the title of the exhibition suggests, the project seeks rather to free the imagination to the idea of plural cosmologies, in which different conceptions of what technology is can emerge.

It is certainly not the first instance in the contemporary art field to take Hui’s book and the concepts he put forth as gateways toward a discussion surrounding technology. When discussing sources of inspiration, Moreno mentions an exchange he made with Hui when the latter was teaching a seminar at the China Academy of Art. He had asked the philosopher how it would be possible to transcribe the theory, which is so heavily entrenched in Chinese thought history that it’s difficult to even for native Chinese to access, to folks back in Colombia, in response to which Hui suggested a search for an own conception of technology, wherever the lived experience lays. In short, rather than being about technology, “Tecnodiversidad” inspects it in relation to the lifeworlds in which their conception becomes possible, building upon such inspections a possible dialog across continents.

§

Moreno and Chen’s curatorial essay Territoriality traces the histories of how internet infrastructures have been built, and how they continue to underlie our, now overwhelmingly digital, daily actions. The stories which the curators traced in their research of how China and Colombia have built up, and since remodeled, their own internet infrastructures reflect two different roadmaps of how countries who arrived late to the modernization party deal with a U.S.-engineered, globally connected internet ideology. Colombia’s case reflects a hybrid model of interconnectedness and national sovereignty. The Colombian government and multinational corporations shaped in tandem the nation’s digital infrastructure and model of digital citizenship. A comparison between forms of digital citizenship between the two countries is intriguing, especially through revelations of how everyday internet services usage, such as streaming music and using cloud services, requires information to pass through multiple terrestrial borders. In stark contrast to the zone of opacity that China has created for its cyber territory, Colombia in fact inhabits a much more international and interconnected position.

Juan Pablo Pacheco, Underworld, 2020. Storyline excerpt.

Courtesy the artist

Internet infrastructure stands as a fitting example of a complex system that, being largely invisible and ungraspable to the layman, continuously dictates our daily lives. A “complex system” is described by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams in their book Inventing the Future (2016) as one which “features nonlinear dynamics, where marginally different inputs can cause dramatically divergent outputs, intricate sets of causes feedback on one another in unexpected ways, and which characteristically operates on scales of space and time that go far beyond any individual’s unaided perception[1].” The near impossibility to have a comprehensible mental image (a cognitive map) that explains our systemic present in a familiar human narrative is an unavoidable issue when thinking about technology today. It might explain why, for things as materially gigantic as submarine optical cables, everyday language always finds the most lightweight, insubstantial similes (“cloud,” “net,” “chain”). Taking the Economy as their example of choice, Srnicek and Williams write, “[W]hile we might have an idea of what an economy consists of, we will never be able to experience it directly in the same way as other phenomena. It can only be observed symptomatically through key statistical indexes… but can never be seen, heard or touched in its totality.”

The question then becomes, how do artists, a group of people traditionally attributed with shamanistic abilities to bounce between realities and dimensions, reconcile the ungraspable totality and our human perceptions? How do the artists of today, who engage themselves with both a hypersensitivity in the everyday and virtuosity in researching information in the public realm, demonstrate an ability to “see double” and bring about this double vision through their work?

§

The online iteration of Guo Cheng’s The Net Wanderer, A Tour of Suspended Handshakes (2019—) in “Technodiversity” leaves a deceptive first impression. A research project originally commissioned within the Digital Earth fellowship program, The Net Wanderer takes on the infrastructure underlying China’s Great Firewall (GFW). By using computer network diagnostic tools to track geolocations of the GFW’s gateway IP addresses, Guo illustrates a physical map of China’s virtual borders[2]. In this online version, the installation which in past iterations have accompanied the piece is missing. In its stead, the online format presents the excitement that every viewer might access the work from a distinct location of the world, data which is reflected instantly by a locator icon in the world map on the artwork’s page. After a brief moment of confusion mixed with frustration, the second half of the piece unravels as the dinosaur game is completed (through inevitable failure). Videos taken by Guo as he visits in real life the locations indicated by the IP addresses appear on the screen, as the viewer is taken on a visual tour to grim-looking facilities, lively public parks or walled-off construction sites.

Guo Cheng, The Net Wanderer – A tour of suspended handshakes, 2019. Visiting record of IP addresses.

Courtesy the artist

The non-accordance between the leviathan searched for and the innocuousness of sites found stirs up an emotional cocktail of confusion, awe and alarm, as if one is attempting a handshake with a Big Dumb Object. The effect is a non-visual montage, a double exposure of two images that, while in no way could be observed from a unified point of view (or by the same biological species), belong to the same entity. The power of montage and the ability to “see double” was key to Walter Benjamin’s conception of history, where the placing of historical facts in the construct of a photomontage, allows for different conceptions of history to emerge, where disparate evidences are not unified by default under an overarching narrative. In our time, one which is marked by tendencies of polarization and purism of opinions, this ability appears increasingly to be a lost art, both in technique and political validity. Still, artists remain in a privileged, albeit precarious position to activate this double vision. Specific to the current context, a double vision we require could be to see a double exposure of the planetary-scale cloud infrastructures in the same frame with a physical human body, or from the perspective of a GoPro camera worn on someone’s forehead, constantly bouncing as the legs switch between steps or swaying while a shared bike is pedaled.

§

Colombia’s fragmented history is laden with occurrences that continue to affect contemporary Colombian identity, including but not limited to Christianity’s spiritual hegemony, erasure of indigenous sacred landmarks[3], African settlements’ influence in the configuration of a national identity[4], and the domestic economic monopolization sequel to the industrial boom. In a discussion between the curators and the artists Guo Cheng and Juan Covelli, Moreno discusses the impact of Latin America’s colonial history on the discourse of the Anthropocene by saying, “it is interesting how the Anthropocene discourse turns the human into a bad actor, while in Latin American history, humans have always been bad actors.” The resulting critical view takes a wildly different path in Colombian artist Juan Covelli’s 2021 video El Salto (a Spanish word whose meaning roams between jumping and waterfall), which plays with numerous attempts to see an iconic Colombian landscape through technology’s eyes. In the dilemma triad of nature, humans and technology, Covelli wonders what it would look like if we take the human out of the picture. In a painterly composition of a valley stretching to a distant waterfall, a green screen blocks – yet simultaneously displays – the heart of the image. A drone camera flies into said valley, taking the viewer on a visual journey, which is later replicated by a software’s internal camera flying through the 3D rendered version of that same location. Near the end of the video mesmerizing AI-generated landscapes appear, which at first glance resemble actual photos edited by a “painterly” filter, but whose “original image” doesn’t actually exist.

Juan Covelli, El Salto, 2021. Video, 12’35”. Film stills.

Courtesy the artist

Through algorithms, 3D capture and modeling, even game developing software such as Unreal Engine, the video relays the life of the Tequendama waterfall inherited in local imagery of Bogotá and its polysemic potentiality. To the Muiscas, the indigenous population of the Bogotá region, the waterfall was a remnant of the creation of the world by the god Bochica. Since the German explorer Alexander von Humboldt, during his celebrated early 19th-century botanical explorations in Central and South America, visited and sketched the Tequendama waterfall, it had been enshrined as an icon of the region’s charm and pride. Today its iconic status clashes with the environmental reckoning after decades of industrial and urban pollution and extractivist mining. The toll taken on the cascade by the history of industry and the evolution of the city is noted throughout the video. In the words of the artist and researcher Barbara Santos in her book Healing as Technology (Curación como Tecnología, 2019) “In cities, above all, we have lost the notion of belonging to the territory, and we ignore that the cartography of the city of Bogotá is not only its careers and streets but a complex body of relationships that feeds on what happens in the cities[5].” Throughout the richly layered history of the Tequendama waterfall, through all its glories and atrocities, Juan Covelli’s mechanical lens looks the natural landscape straight in the eyes.

§

The section “Systems Representing Themselves” mentions how the usage of tools (or Qi 器) can be understood as not exclusive to human evolution. In their methods of conceiving a connection between Chinese and Amerindian ancestral cosmologies, the curators neither created similes nor forced parallels. Instead, they took on the legacies of both to imagine technology as not being an exclusive invention of humans, but rather as an inherent part of the rest of the living world. From these perspectives, plants, animals, lagoons, forests and the Earth itself are considered bodies that by themselves are capable of creation and computation in inconceivably complex manners. Bees create perfect hexagonal cells to store and transform pollen into honey, protecting their hives in the meantime. An entire forest can reconfigure their chemical composition through the transmission of information by electrical pulses and low sound frequencies. Here, the curators introduce viewing computation and transmission of information as tool-making prototypes that evolve in the same way as forms of life.

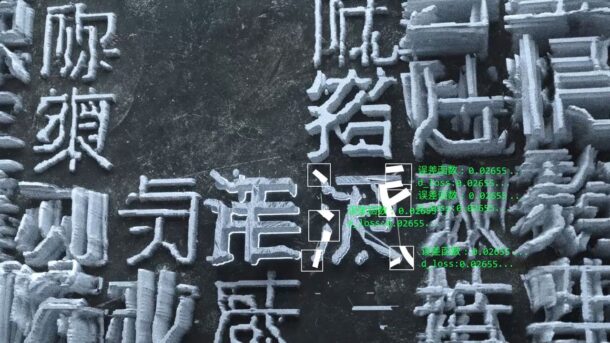

Such is the case in Chen Xin’s video Thus (2020-2021), which resurrects the legend of Cang Jie, forefather of Chinese characters. By utilizing generative adversarial networks (GAN), Chen reconstructs an ancient and mystical process: the making of a language. The title “Thus” comes from the story of the Japanese monk Akie-sama (MingHui) the venerable, who made use of Chinese characters to spread his doctrine, even though these characters only served as vessels to replicate the sound of his oral language, without retaining their original meaning. The characters are reconstructed by coding language, vectors, and mathematical formulas. From this process, the artist experiments with giving tools (in this case the ideograms and computation) agency beyond human-legible meaning, setting into motion its own lineage of evolution.

Chen Xin, Thus Shall Be, by the monk Akie, 2020. Video, 2’52”. Film stills.

Courtesy the artist

“Systems Representing Themselves” fathoms upon the possible worlds existing in the unexplored dimensions between computation and nature. How can we identify this relationship through information systems beyond those based on personal computers? How are they represented? Juan Pablo Pacheco develops this idea by creating a mythical story about a mollusk that lives down in the ocean depths. Crawling along 5800-mile long optical fiber cables, the tick-like creature feeds from and transforms the structure of the cables. Throughout the story, Pacheco remarks on the influence of man-made infrastructures outspread even in the sea, creating a tale about an animal that, despite living kilometers below mankind’s inhabited earth crust, still could not avoid interference in its biological composition, as copper, plastic, and fiberglass are discovered in its belly.

§

Confrontation with massive, silent entities which we don’t understand is not unique to the present. On the contrary, it has accompanied human history since the beginning. The histories of how cultures make sense of the cosmos, nature and human life are intriguing cases of narrating the inconceivable. Chen and Moreno’s essay “Online Esoterism” makes the intriguing claim that it is the esoteric component of a society’s culture which grants us a more direct and unmediated view into its cosmology. Superstitions and beliefs delineate which events would be possible and which impossible, which in turn sets the direction and limitations of that culture’s technology. Under this structure, it is all the more interesting that esoterism (or “xuan xue” in Chinese) continues to thrive even in digital form. In our conversations, Chen brought up a movement by the Chinese government a few years prior to encourage people to pay homage to their ancestors digitally, instead of burning paper, which is harmful to the environment. The call was met both with interest and ridicule, as many people believe that paying homage via the “immaterial” format makes it no longer “ling (灵).” “灵” is a difficult word to translate to English, the closest in meaning would be “effective,” but one in which the cause-effect relationship is between a subjective wish and an immaterial event, channeled by an esoteric logic. “Whether it’s burning paper or reading paper books,” says Chen in our interview, “the commonality is that if we do the same work with lower tech and higher costs, the chances of achieving the goal would become better.” This apparent paradox between media and effectiveness is further teased out in Shen Bin and Li Kunze’s work, Contemporary Talisman (2021).

Shen Biin and Lee Kwan Chak, Contemporary Talisman, 2021, mixed media.

Courtesy the artist

Contemporary Talisman takes the “techne” side of cosmotechnics quite literally. Inspired by how, in ancient China, the Fulu (mystic calligraphic writing with incantation powers) were an instrument to channel invisible natural forces to balance the Yin and Yang and fulfill the wielding subject’s wishes, the artists Shen Bin and Li Kunze imagine an alternative present, in which they are two Taoist monks (道士) with the ability of channeling this ancient craft to solve present-day problems. For the exhibition “Tecnodiversidad”, three versions with different functionalities are created, suiting three specific contemporary desires. “Bitcoin does not stop growing” (比特涨不停) blesses the owner with crypto-wealth. “Invisibility and protection of the digital world” (网届隐身遁甲), advised to be attached to the backs of your smart devices, creates an invaluable layer of protection that prevents data leakage. Finally, “Protection and attraction of digital love” (数字爱情御守), which could be customized by writing down names of significant acquaintances, promises better matches in dating apps and augmented security in existing relationships. Shen and Li were inspired in part by a lesser-known sequel to Water Margin, the Chinese household classic, named “Heroes of the Swamp.” In this Qing Dynasty sci-fi-esque fantasy, the Taoist monk Chen Xizhen was able to overpower primitive tanks, submarines and mechanic lions from western technology with a simple but powerful Taoist talisman called the “Qian Yuan Mirror.” Like the image of an elaborately calligraphed Taoist Fu on the back of an Apple Macbook, the Qing dynasty novel creates to our contemporary eyes a juxtaposition, a clash of two instruments, each firmly embedded in its own separate universe. Do we truly have an answer which one would be more effective?

§

In our personal experiences, the first steps in navigating an unfamiliar culture tend to rely heavily on recognition. Do we have the same thing in China/Colombia? Do we have the same thing, but differently? Do we have another thing with the same purpose? But to recognize is not to know. To recognize is always immediately to compare with an existing concept, instead of actually learning about an unknown one. In the process of recognizing instead of knowing, a discrepancy always exists and, in some cases, are never reclaimed. As self-proclaimed travelers between cultures, curators often share a hypersensitivity for discrepancies. A hypersensitive nose that always detects fishy smells, warning that things are not as how they are written.

Collaboration between curators from different corners of the world is not unheard of. Even between the bests in the field, the beginnings of their conversations still sometimes read like the first mingling party of Erasmus students. But that might be just what we need when thinking about something as unthinkable as either technology or cosmology. Moreno and Chen act for each other as culturally interested, colonially disinterested outsiders. In their essays, Chinese readers might find to their amusement and delight details that betray an anthropologically aloof bystander, noting down the natives’ oblivious behavior in a tone conventionally identified as a “foreign guest (外宾语气).” Lived experiences and its wonderful stock of unimaginable technological variations are the undercurrents that carry conversations between theory and art, between cross-continental cosmovisions.

Notes:

[1]Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World without Work (Brooklyn, NY: Verso Books, 2015).

[2]Cheng Guo, “A Tour of Suspended Handshakes,” Digital Earth (blog), October 11, 2019, https://medium.com/digital-earth/a-tour-of-suspended-handshakes-2b1b699c9cf2.

[3]During four hundred years, Christian missions overtook sacred places in indigenous territories and converted them into churches and monasteries. These places were housed by figures like Jesus and Maria, and banned the understanding of the territory. This clerical pedagogy considered the native cosmology, political systems and architecture as underdeveloped.

[4]Due to slavery trade, many African people brought to America created their own settlement where identity evolved and currently are the bastion for the recognition of a good part of the immaterial heritage in the Colombian culture.

[5]Bárbara Santos, Healing as Technology, (Bogotá, IDARTES, 2019)

David Felipe Suárez Mira is an independent curator, producer, researcher, museum consultant and journalist living in Bogotá.

Xinyi Ren is a curator based in Berlin, currently a Master’s candidate at Humboldt University in Cultural Studies