Traces of Lu Pingyuan: In the Messages of the Whole World

| November 1, 2023

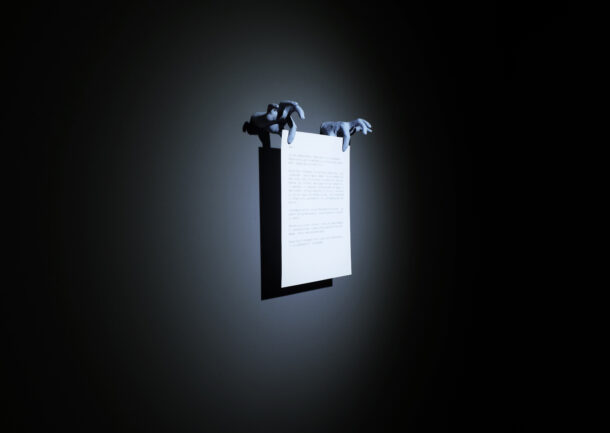

Story, 2013, Performance, Dimensions variable, Courtesy the artist

Chapter 1

Turning Stones into Sheep

Huang Chuping was a native of Danxi. At the age of fifteen he was made to tend sheep for his family. There was a master of the Dao who, noting his goodness and attentiveness, took him to a cave in Goldflower Mountain. For more than forty years Chuping did not miss his family. Meanwhile, his older brother, Chuqi, searched for him without success. Then one day there was a master of the Dao who excelled at divinations, performing in the market nearby. Chuqi approached and requested a divination [of his brother’s whereabouts]. The master said, “There is a shepherd lad on Goldflower Mountain. I wonder if it might be your brother?” So Chuqi followed the master [to the mountain], where he searched for and [at last] found his brother. They had mixed feelings of joy and sorrow on seeing each other. Chuqi then asked where the sheep were. Chuping replied, “They’re close by, on the eastern side of the mountain.” Chuqi went to look, but he saw no sheep there, only countless white rocks, so he returned and said that there were no sheep. “The sheep are there, it’s just that you didn’t see them,” Chuping responded, and so they went together to have another look. “Sheep, get up!” Chuping shouted, and at this the white rocks all stood up and turned into several myriad head of sheep.[1]

——Ge Hong, Shenxian Zhuan

In 1984, a boy named Lu Pingyuan was born in Jinhua, Zhejiang. From a young age, he had a passion for drawing, comics, and storytelling. Both of his parents were doctors; during his childhood summers, he often spent time at home by himself. After the Chinese economic reform, Zhejiang became home to many light industrial plastic factories that produced a plethora of plastic toys. At the little boy’s home, too, there were a lot of them. He would hold these figures that came from factories and unknown tales, tell stories of their adventure around the world, and regard them as his sincere companions.

The stories of Huang Chuping and Lu Pingyuan both take place in Jinhua, Zhejiang. The former is clearly a legend—Huang was later regarded as the benevolent “Huang Daxian”, who was famous throughout the Cantonese region. “Turning Stones into Sheep” is his best known miracle. The latter seems to be a commonly told anecdote when you trace an artist’s creative trajectory—Lu went on becoming a professional artist based in Shanghai; his exhibitions were to display giant toys and puffed snacks. The essential difference between the two lies in the fact that when Huang shouted “Sheep” at a stone, it pointed to a future that awaited for its substantiation; in this case any response would be quite an astonishing occurrence. By contrast, saying “you have once traveled through space” to plastic toys is an unverifiable fabrication of imagination. However, these two stories still resonate in a marvelous way—in both, humans animated lifeless things and endowed life’s encounters upon objects through narratives and words. Yet as for whether the stones and the sheep are merely products of human imagination, and whether experiences are concrete or merely a mirage, the answers remain uncertain. In this sense, Lu can also be considered someone who “turns stones into sheep,” except he opens another realm, a different fictional space-time where life resides.

Lu Pingyuan’s studio in Songjiang District, Shanghai resembles an infinitely expanding container, filled with heterogeneous items that amounts to a micro universe: the Barbabeau sculptures from the previous years, a series of drawings of a six-fingered hand generated by an AI glitch, old magazines, new toys, and bottles and jars can be found scattered throughout. However, the most striking are those that would be called the ‘readymades’ in modern art: smiley face biscuits, Thomas the Tank Engine, and M&M characters. These humanoid figures devoid of personalities are what Lu easily notices. Their virtual existence carries obvious contradictions: they look like humans, speak for themselves, but are at the sametime not taken seriously. When biting into the biscuits, most people do not pay attention to the faces but consider them objects that, despite resembling faces, lack sentience. It is important to note that here I am not talking about animated characters in Disney movies who may already have their biographies as well as iconic faces and voices; instead, what is concerned are the cheap, mass-produced figures who happen to have a humanlike shape. For example, Lu often mentions that when medicine commercials show up on television, organs with mouths, eyes, and two hands would pop out in yellow, pink, blue, and other colors. No one cares about the names of these kidneys and hearts, but these characters can instantly even out the pain and make sensations disappear altogether.

“Story” Series, 2012 to present, Text and installation, Dimensions variable, Courtesy the artist

In the 2022 exhibition, “One Night at a Gallery”, Lu Pingyuan drew upon two different frames of references in animation. The first genre, produced in 1978 by Shanghai Animation Film Studio, is the animated film Hualang Yiye (One Night at a Gallery), in which two personified figures representing political ideologies’ censorship, a stick and a hat, vandalize and shut down a children’s art exhibition. Subsequently, the children, a rooster, and an elephant depicted in the exhibited paintings come alive, unite together to clean up the black inks that destroyed artworks and defeat the enemies. These figures and humanoid characters all have their own personalities, genders and backgrounds. The other genre, motion graphics such as the aforementioned medical advertisement and educational videos that were repeatedly played during the pandemic to instruct on handwashing and mask-wearing, serves primarily to convey information in public settings. In this genre, characters lack distinct individualities, and the backgrounds in the animated works, too, are often blank color fields. Despite the two traditions’ shared use of humanoid characters, these figures exist in drastically different modes—one has free will, the other merely color blocks with a semblance of life. Lu often incorporates these animation and cartoon characters into his paintings and sculptures. His exhibition space is covered in shades of orange and pink, creating a stark contrast to the reality outside the art museum. Stepping into this space feels like entering a three-dimensional space turned from television advertisements; one is being transported into a suspended state of unreality.

Looking at Lu Pingyuan’s recent creations, one might wonder if these vibrant creations are merely transplants and simulations of popular visual culture. The infinitely splitting images and numerous sculptures reveal the artist’s pleasure in laboring and molding figures, but there is a hard-to-conceal repetition in the media materials, aesthetic features, and creative ideas among different works. These commodified humanoid characters, already a sort of simulation themselves, are enlarged, reconfigured, and simulated once again, or simply relocated into the gallery. The dazzling and exaggerated visuals appeal to trendy brands and lend to their internet fame, while the lively and communicative cartoon characters also align with popular cultural consumption. What exactly is Lu Pingyuan trying to say? Whether it is satire, carnival, or redemption, it is difficult for researchers to find the answer. “One Night at a Gallery” is especially unique among these projects, because the animation it cites has a clear time and space (that is, the museums during the Cultural Revolution). The selected element—fences—not only supported the paintings and sculptures outside the China Art Museum during the Star Art Exhibition, but they were also one of the things people are most familiar with in life during the recent pandemic. These heavy and sharp objects in real life enter the animation-like exhibition site and obtain real freedom, making the approach of transformation and reposition more authentic. Despite these fences do not have eyes or mouths, they become protagonists in the exhibition, or even characters.

The endless transformation of shapes and the question of whether the true essence of things exists reminds one of the dual projections carried by plastic in the 20th century. On the one hand, it is now the cheapest, most disposable, and seemingly inexhaustible synthetic material, despised for its contribution to soil and water pollution, feared for plastic particles entering our digestive systems and bloodstream, and associated with lower class. On the other hand, there was a time when plastic was synonymous with magic. In 1957, Roland Barthes referred to plastic as a “miraculous substance”, writing that “plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation […] it is less a thing than the trace of a movement.” From the nineteenth century onwards, materials like celluloid, synthetic silk, nylon, and foam were invented using raw materials such as rubber, cotton, and petroleum, etc. Turned from natural substances into a fabricated material, plastic can be soft and firm and can take on the shape of anything in the world. It can replace pearls, ivory, and wood and transform into combs, fabrics, and vascular stents. People believed that plastic would protect the Earth and promote democracy. The quality of plastic’s infinite transformation made it a close sibling of science fiction, both becoming synonymous with immortality and the future. In this regard, plastic and science fiction are like sorcery to a sorcerer. The magic lies not in the result of a spell but in the transformative process. Whether plastic is worthless or a worldwide marvel? The ambiguity, deception, suspicion, and metamorphosis it entails are akin to the essence of life itself.

In the last two decades of the twentieth century, Lu Pingyuan, with plastic toys in his hands, also immersed himself in imaginations of the future. Science fiction magazines then, Omni (ao mi) and Science Fiction World (kehuan shijie), are interspersed with advertisements for astronomical telescopes, as seen in the magazines in the film Journey to the West (2021), while striking American-style comics dominate their covers. The emergence of Japanese and western animations later blew Lu’s eyes and mind. To him, Japanese manga was his Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden (jiezi yuan huapu, a foundation book for traditional Chinese painting). (Lu has also copied Pipi Dawang and Crest of the Royal Family.) However, after the turn of the millennium, the outpour of cultural creativity was gradually transformed into a scaled-up and assembly-line production. Countless faces are produced, and images are no longer precious. Perhaps both we and Lu Pingyuan need to return to the moment when the shepherd boy Huang Chuping turned the stones into sheep, which makes us wonder: within the constant metamorphosis of life, what truly matters?

Chapter 2

The Place of Escape

An artist dreamt of entering a large temple. Inside the temple, there were rows of Buddha statues, but upon closer inspection, the statues were all of great artists like Picasso, Monet, Dali, and Beuys. In front of them, there was a table with a book titled Art History of the Next 300 Years. The artist couldn’t wait to flip through the pages to see if he was mentioned. After searching for a while, he was disappointed to find that his name was not in it. The great artists laughed and said, “It’s okay, it’s normal not to be in here. You can go to the temple next door; they oversee the regional artists.” The artist left and arrived at a slightly smaller temple nearby. Inside this temple, there were also rows of Buddha statues, but upon closer inspection, they were all of great Chinese artists like Qi Baishi, Zhang Daqian, Xu Beihong, and Huang Binhong. There was also a book on the table titled Art History of the Next 300 Years in China. The artist eagerly searched through the pages to see if they were mentioned but again found nothing. These artists also smiled and said, “It’s normal not to be in here. This place is not for ordinary people. If you still would like to try, you can go to a small temple at the intersection outside.” So the artist left that temple and arrived at the intersection, where he saw a small temple behind the bushes, about half a person’s height. He lowered his head to take a look and saw a very small Buddha sitting inside. He bent down and entered the temple, and upon looking closely, he realized it was himself.

—Lu Pingyuan, “The Temple of the Art King” (yi wang miao), 2016

When Lu Pingyuan was young, he dreamed of becoming a cartoonist. In college, he studied graphic design. As he entered the realm of contemporary art, it was a time marked by the bursting of the market bubble, where the once triumphant march forward was gradually replaced by doubt, cynicism, and disappointment. Amidst this labyrinthine landscape, young practitioners of contemporary art grappled with a myriad of questions: How does the system of contemporary art truly operate? What are the rules of the game within the art gallery? How should artists and curators collaborate? How do we judge what constitutes good art and a good artist? These questions haunted the young artists in their artistic endeavors. Parallel to the emerging consciousness of curating in mainland China, artists began to orchestrate their own movements, seeking solace in the sanctuary of collectives, engendering an “institutionalization of self”, and actively engaging in institutional criticism, reevaluating their relationship with the external systems of the art industry. They also began venturing to different corners of the world, eager to glean insights from fellow artists, sought residencies far and wide, yearning to find what kinds of lives artists in foreign lands were living.

In this captivating tableau, Lu Pingyuan participated in the group GUEST and co-founded the digital magazine PDF. He captured the elusive creatures of galleries, turning the gallery into an impromptu menagerie. He skillfully installed charging cables within the sanctuaries of art, created a whimsical spectacle by inviting friends to charge their equipment. He also entrusted his very own wallet to a security guard of the gallery. Perhaps the most renowned of his works in this vein was a performance in 2011. With the gaze of the crowd upon him, he fervently used his hands and feet, struggling to climb a pedestal of equal height and build to himself, engaging in repeated battles until he reached the pinnacle. This performance, titled A Readymade, reinvigorated the spirit of Piero Manzoni, an Italian artist, and his 1961 work, Base Magica – Scultura Vivente (Magic Base – Living Sculpture). However, Manzoni’s pedestal stood at approximately 60 centimeters, while Lu Pingyuan’s towering base reached 170 centimeters. Manzoni exuded an air of serene composure, while Lu’’s ascent was accompanied by a sense of breathlessness and drenched in sweat. This arduous endeavor vividly depicted the anguish experienced by young artists of that era.

In the “Capsule” exhibition in 2011, Lu Pingyuan presented self-rejected proposals. He believed that even if these ideas were materialized into artworks, they would not be worthy of entering art history or art museums. In the exhibition “Waiting for an Artist” in 2013, gallery staff continuously washed the artist’s clothes, ensuring that they were constantly hung and left to dry, emphasizing the absence of the artist’s physical presence. Here, the incarnation of the gallery shifted from a capsule to clothing, awaiting the entry of human flesh to assume the role of the “artist”. In the exhibition “The First Artist” in 2021, Lu points out the success of a failed artist. The French animated series Barbapapa from the 1990s depicted a character named Barbabeau, an artist who always carried a sketchbook or a palette. In Lu’s perspective, Barbabeau’s drawings, sketches and sculptures merely repeated existing artistic methods, materials and styles, rendering him a destined failure excluded from art history. However, Barbabeau’s black plush body, like Barbapapa, could transform into any shape. Lu envisions this boundless metamorphosis of physical form as an avenue for transcending and subverting the established order of art history, allowing Barbabeau to transcend his perceived limitations and emerge as the “first artist”. Clearly, despite moving away from directly deconstructing the art and museum systems, Lu Pingyuan continues to discuss who holds the power and standards to recognize art through alternative contexts. His quest to the intricate mechanisms of reality, particularly within the art system, remains ongoing, albeit in a shift from confrontation to an embrace of escapism. Furthermore, he seems to possess a desire for liberation, urging Barbabeau, or anyone for that matter, to break free from existing artistic notions and realize their own freedom without conforming to any paradigm.

In 2014, Lu Pingyuan claimed to have encountered the just deceased On Kawara in his dream. The spirit of Kawara implored Lu to undertake the continuation of his “Today” series, a collection of date paintings that transcended the mere passage of time. Many people, of course, don’t buy into such a narrative—this “dream” might just be a way for him to connect with great artists, romantically continuing to produce products that have already been validated by the system and the market. Dreams, or rather untouchable proclamations and narratives, held a particular allure within Lu’s artistic praxis. Several years prior, he had already begun writing stories or proposing unrealizable ideas. These brief stories often appear to be inexplicable. Their origins and resolutions shroud in enigma. Although they possessed an air of whimsy, they resisted the archetypal emotional crescendos found in the ghost stories written by Pu Songling or the allegorical nature of Grimms’ fairy tales. These stories lack technique, style, or explicit messaging, veering away from conventional storytelling tropes. Their purpose did not lie in transforming the reader, but rather in capturing the ephemeral essence of metamorphosis. In some way, the intangible stories of Lu Pingyuan sought liberation from the shackles of authorship and stylization, evading easy classification. While the written “stories” could be formally connected to the early conceptual artists who treated proposals as artworks, resisting the fetishism of collecting and the market, the transient nature of the written form was more akin to creating distance between the stories and the narrator. He yearned for these stories to depart from fixed textual arrangements, exist within retelling, and be activated by diverse individuals in different tones, manners, and idiosyncratic details. This approach of directing towards the individual’s interior and different embodiments transformed the life forms of artworks into the fluid circulation, magic transformation, and ceaseless interplay of information.

Writer Shi Tiesheng once depicted in his Notes on Principles the scene of countless messages drifting through the universe, taking form as faint vibrations connecting life, emotions, and objects. Speaking in the first person of these messages, he softly calls out, “Come, listen to me. I exist not only within my own body but also within all the messages of this entire world, within all that is known and unknown, within the desires of all people. Thus, it is eternal and immortal…” In a certain sense, the story of Lu Pingyuan is also such a message. However, as an artist, Lu Pingyuan’s position in his own creation is not entirely light. In the process of weaving stories, the artist himself would like to recede, or rather, he aspires to become the ever-changing and unrestricted story—instead of being an artist of ready-made artworks, he preferred to be an ever-present incarnation of information. In a conversation, Lu Pingyuan expressed, “I have instances where I feel as if I am a transient entity, a phase. We are so used to being a whole ‘person’. The ‘I’ is actually a lush garden, composed of countless billions of temporary individuals. When the ‘person’ ceases to be, the components within the body merely revert to their original places.” However, in the actual operating art system, Lu Pingyuan is an artist, he is still labeled, and his creations still need to circulate as entities, gradually turning into continuously produced sculptures and paintings. Ultimately, are the stories just props to rationalize the production of works? Or, are they a way for Lu Pingyuan to create his own context and ease the anxieties in reality?

Chapter 3

The World of Sentience

I wish to have a large ship that can carry all beings from Shimen-wan and the world, sailing to a place of eternal peace.

— Feng Zikai, 1939

The title of Lu Pingyuan’s solo exhibition in 2020, “Imperishable Affection”, takes its Chinese name “A World of Sentience” ”from an eponymous work by Feng Zikai. The inscription on that painting reads “Yuan-yuan Tang Painting Scroll”. Constructed in 1933 in Feng’s hometown, Shimen-wan, Yuan-yuan Tang existed as more than a mere physical structure. Before taking physical form, Yuan-yuan Tang “originally existed as a spiritual entity”, dwelling within Feng Zikai’s imagination. From the architectural design down to the tiniest details of nature, Feng meticulously crafted a space that sought a harmonious interplay between form and spirit, embracing an aesthetic of unadorned simplicity. The World of Sentience perhaps portrays Feng Zikai’s work desk, which brims with penholders, teapots, cups, alarm clocks, pens, ink, and folding fans… A vase even holds several flowers. Despite the simplicity of Feng’s drawings, they exude a remarkable vitality. Within this painting, he bestows each object with a sentient quality, endowing them with individual faces and unique expressions. Smiles and nods grace some, while others emanate fierce, wide-eyed gazes of fury. “Sentience” finds its roots in Buddhist philosophy, referring to things that possess consciousness and emotions, including humans. During his time as an educator in Guilin, Feng Zikai shared his belief that still life, often perceived as inanimate objects, could be seen by painters as living entities. He imagined these objects as having emotions and a life akin to that of the artist’s own. Such a notion finds direct embodiment in his painting The World of Sentience. However, the year 1937 brought the encroaching presence of the Japanese army upon Shimen-wan, prompting Feng Zikai and his entire family of ten to hastily escape on a boat, leaving Yuan-yuan Tang to succumb to the ravages of war. The book desk portrayed in The World of Sentience undoubtedly met the same fate, reduced to ashes. In the aftermath, Feng Zikai mourned deeply for the countless sentient beings that fell victim to the brutal carnage, holding onto the hope that a “large ship” could carry his beloved ones and cherished possessions through the harrowing ordeals they faced.

Lu Pingyuan’s “story” and exhibition are like such a “large ship”, carrying sentient beings away from the bleak reality. He states, “Considered as monsters or fantastical creatures, there is no place for them to exist in today’s world. In fact, many of my works are an invention of space, allowing them to survive.” However, the paradox of his creations lies in the fact that he is most concerned not with those enlightened spirits but with the most humble and spiritless lives. In comparison to the protagonists within the enchanting realms of Disney animations, where resources and narratives abound because of their status as selling goods in capitalism, those Motion Graphics, the cookies adorned with eyes and mouths, and other similar creations seem resigned to a fate of servitude, like a marginalized class of functional objects. It is not so much that the latter lacks life, but rather they never had the opportunity to grow and therefore, remain “sentience-less”. As deities, ghosts, monsters, and spirits gradually recede from our everyday life, their roles are supplanted by commodities and advertisements, masquerading as living beings. Lu almost “recycles” these easily created life images, turning his studio and exhibitions into shelters that house the refugees who have nowhere else to go, discarded and abandoned. Their superficiality and falsehood as ephemera, when contemplated, evoke a sense of fragility, inviting us to grieve their plight. It is not the meager lives themselves that lack sentiment, but rather the merciless reality, rife with oppression, violence, and relentless pursuit of profit. It is within the realm of fiction, where judgments are suspended, that perception finds respite, albeit fleetingly.

French artists Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno once made a low-cost purchase from a Japanese animation company’s repository of unnamed characters, acquiring a female animated figure whom they named “AnnLee”. Subsequently, they extended invitations to numerous friends to participate in the creative process. The resulting project was titled “No Ghost Just A Shell”, echoing the renowned Japanese anime series “Ghost in the Shell”. AnnLee became an integral part of various artists’ works, assuming the form of a standing sculpture, confessing her story in video recordings, gracefully dancing in mid-air, and even being captured amidst the night sky by the brushstrokes of fireworks. This artistic endeavor bears striking resemblance to Lu Pingyuan’s own practice, both striving to emancipate those who have been brought into existence solely as nameless shells. However, Lu’s approach to rescue is less embellished, exhibiting a restrained sympathy and avoiding excessive manipulation of their physical manifestations. His actions are imbued with a sense of doubt, fostering an environment of equal footing between the rescuer and the rescued.

The press release for “The First Artist” mentions the animated series “Barbapapa” as “artist’s memory” modifier. A widely known animation, through memory, is thus brought into the artist’s internal context, diverging itself from the animation’s dissemination. If Lu Pingyuan’s stories are real in any sense, it might be the act of escaping from reality. For Lu, “the large ship” alternates sometimes as a memory, sometimes a dream, sometimes a story. These concepts coexist parallel to, and even separated from, reality, holding the capacity to be shaped, enacted, and re-narrated indefinitely. If there is any reliance, it is on himself, perhaps even a not-so-clear self. Perhaps now is the moment when Lu Pingyuan is breaking down the boundaries between tangible forms and intangible messages—people, objects, stories, dreams, and memories, are all containers in constant transformation, capable of rescuing and sheltering one another, temporarily detaches Lu from the art ecosystem and societal reality, momentarily stepping away from the heated and intricate political landscape. His journey spans inward, outward, towards imagination, towards turmoil. However, might there be a moment, where an absolute touch can penetrate the interface between fiction and reality?

[1] As translated in Robert F. Campany, To Live As Long As Heaven and Earth: A Translation and Study of Ge Hong’s Traditions of Divine Transcendents, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press, 2002, p. 309.

Translated by NIE Xiaoyi and Jiang Yuwen (with the help of ChatGPT)