Dark Play: Ontological Life Experience of Game Modification

| September 18, 2024

The Famicom (short for “Family Computer”), released by Nintendo in Japan in 1983, was Nintendo’s first video game console, following the line of dedicated “Color TV Games” systems from the late 1970s.

The highly anticipated game Black Myth: Wukong, set for official release this August, previously unveiled a 12-minute demo in 2021. Within this demo, a few lines of dialogue resonated deeply:

In many strange dreams, I’ve encountered you all.

You came together by serendipity, each with a distinct purpose.

You, aspiring to fulfill the unfinished quests of your predecessors, seek perfection in virtue.

You, unwaveringly yearning for a name that echoes through ages, aspiring to celestial glory.

You, longing to transcend the Three Realms, seeking tranquility and liberation.

And then there’s you, unattached, content with a hearty meal, living simply in bliss.

But I’ve long seen through you all!

Filled with grand sentiments and noble aspirations, yet deeply entangled in worldly fame and gain!

You chant of fate beyond control, yet firmly believe your own path is the chosen destiny.

Ha ha, how pitiful, O seekers of the scriptures!

As long as idols linger in your hearts, they will one day become insurmountable obstacles on your path of spiritual practice.

Perhaps this is why Game Science named their game “Black Myth.” According to Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno of the Frankfurt School in their Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944), “Mythical forms encapsulate the essence of existing things: the cycles of the world, fate, and domination are accepted as truth, and hope is abandoned.” They argue that myth transcends mere narrative, constituting a form of knowledge that shapes the fundamental order of human existence. To dwell in this world necessitates adherence to the truths and order embodied in myth. Consequently, we proceed meticulously along the path indicated by its truths, navigating through turbulent waters until the anticipated dawn emerges on the horizon. Belief in myth marks the abandonment of personal hope; rather, hope is shattered by the radiance of myth. In this radiance, myth assumes the role of hope itself, casting a spectral shadow of the Other over our innermost selves and becoming what is known as an “idol.”

The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) was released in 1985 in the US and was distributed in Europe, Australia, and parts of Asia throughout the 1980s under various names.

Myth presents itself as light, so the opposite of myth must be darkness. If we cling to hope, we may only glimpse the faint flame of individual spirit behind the myth. It appears that, like the protagonist in Black Myth: Wukong, we aspire to “release the idols in our hearts” and overcome the “insurmountable obstacles” within. From that moment, we cease to be destined protagonists and transition from light to darkness, from myth to black myth. The concept of black myth evokes the words of the mystic Meister Eckhart: “The ultimate purpose of existence lies in the darkness or ignorance of the hidden divinity. The sacred light illuminates existence, but darkness cannot grasp it.” In essence, the revelation brought by a game such as Black Myth: Wukong does not lie in completing a predetermined spiritual journey. We are all seekers of scriptures, yet we must recognize that no mythical fate dictates our return path. Therefore, darkness symbolizes boundless life, allowing our games and lives to breathe in the abyss of the unknown and ignorance, enabling us to explore an uncharted world with the tentacles of games.

Indeed, according to the distinction between myth and black myth, we can discern two distinct attitudes towards gaming: when we purchase or download a video game, the question shifts from “Why do we play it?” to “How do we play it?” For a novice player, understanding the game requires an exploration of its basic mechanics. Typically, game developers provide brief guides on game operations and plot progressions. In the initial stages, patient tutorials guide players on gathering materials, combat techniques, forming alliances, and progressing the storyline. Moreover, players can access detailed online guides, which offer step-by-step instructions for collecting items and weapons to easily complete the game. The narrative of these guides mirrors the mythic narratives described by Horkheimer and Adorno. For instance, in Elden Ring (2022), many novice players follow tutorial videos on platforms like Bilibili or the Chinese version of TikTok. They quickly teleport from the Dragon-Burnt Ruins to the Sellia Crystal Tunnel to retrieve the Meteorite Staff from a corpse in Sellia, Town of Sorcery. This strategy becomes a popular starting point for mage-type players. While following these guides simplifies the early stages, players under this “mythic” guidance lose the spontaneity of exploring and traversing the game world independently. This approach strictly adheres to the rules of the mythic order, playing within the enlightenment of the game’s intended revelation. We can term this approach “light play,” characterized by strictly following game directives and achieving objectives.

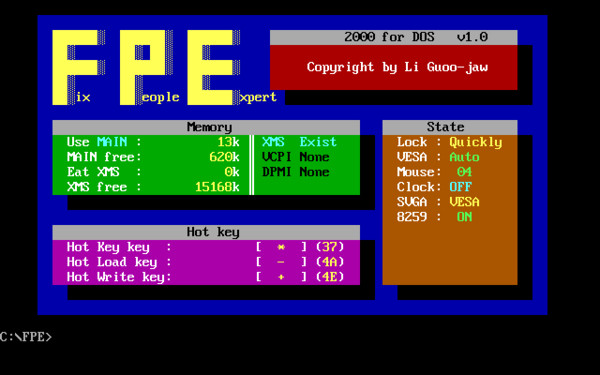

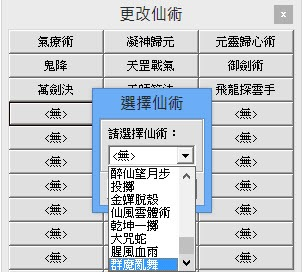

Interface of FPE 2000 for DOS, Version 1.0

Following the dichotomy of myth and black myth, can we identify a form of “dark play” distinct from light play? What does dark play entail for gamers? If light play involves strictly adhering to the mythic revelation (in video games, this manifests as following game strategies and tutorial videos), then dark play entails defying this order—playing the game not according to its predetermined objectives and methods. For example, in the movie Ready Player One (2018), the protagonist Parzival, after completing the three game challenges set by the OASIS company, reaches the final stage: a 1970s pixel game. The game designer, Halliday, intended for players to enjoy the process rather than merely focus on clearing the game. Therefore, Parzival’s path to victory involves not completing the level conventionally but rather circling around a block, uncovering a hidden bonus scene. In essence, dark play is a form of improper play, deviating from the prescribed goals and procedures of the game. In dark play, every experience can be the establishment of a new game. The dominant influence of the game designer fades away, allowing players to redefine their characters within the game world and fundamentally alter the game’s nature through this reinterpretation.

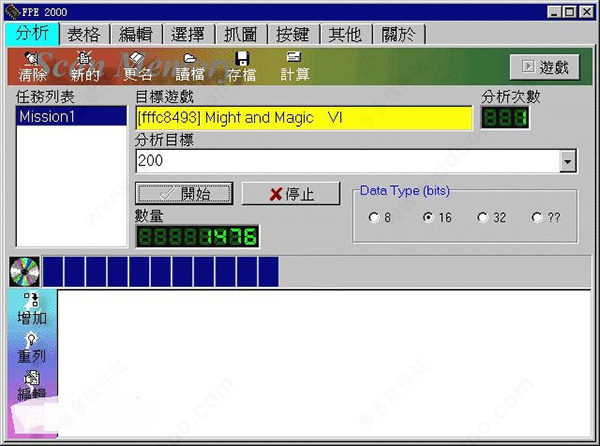

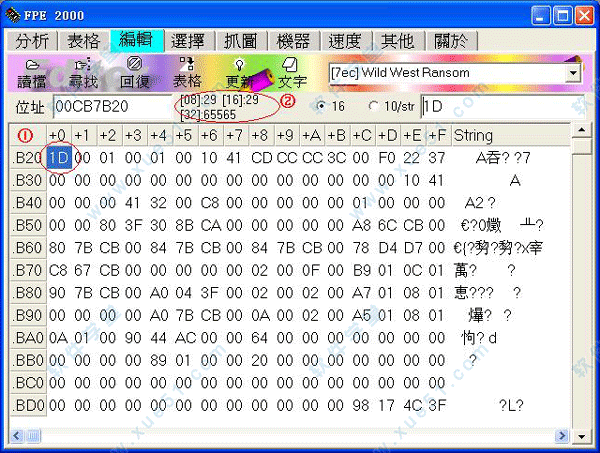

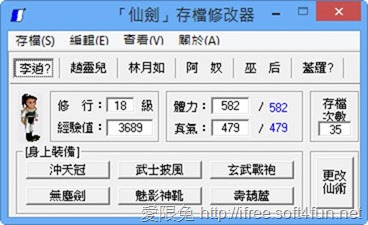

If dark play encompasses various forms, perhaps the most renowned type is game modification. From the early days of single-player games to the present, game modification has evolved alongside game development. The more sophisticated games become, the more intricate the modifications. In the era of consoles like the Family Computer (Famicom), games such as Contra (1987–) allowed players to input the Konami code (up, up, down, down, left, right, left, right, B, A) to start with 30 lives instead of three—a sanctioned cheat code for dark play. With the advent of Personal Computer (PC) gaming, specialized modification tools emerged. In the disk operating system (DOS), for instance, tools like Fix People Expert (FPE) or Game Master (GM) were used before launching a game. These tools functioned by tracking data changes, identifying the game’s data storage locations, and altering them. A notable example was the 1995 version of Chinese Paladin, modifiable using the FPE tool. For instance, when Li Xiaoyao ventures out of town to practice monster hunting, there’s a value that increases with each monster slain—this value represents experience points. After defeating a small monster and gaining 14 experience points, you can activate FPE and input this tracked value of 14. Returning to the game, after killing another small monster and gaining 28 experience points, you can reactivate FPE and input 28. By repeating this process several times, you can pinpoint the exact location where experience points are stored in hexadecimal format. This allows Li to quickly level up beyond what’s normally achievable early in the game, enabling him to defeat small monsters, elite enemies, and bosses with just one hit. Following the same principle, players can also modify the protagonist’s blood bar, currency amount, and inventory. In certain games, it’s even possible to alter the types of items, the protagonist’s attributes, or the martial arts skills learned. FPE and GM offered considerable freedom in early single-player games. While some players sought rapid progression, others valued the challenge and strategic depth of the game itself. For the former, the primary goal was swift advancement through the game rather than overcoming its challenges. Tools like FPE, GM, and Kingsoft Knight were thus indispensable during the DOS and Windows 95 era, allowing gamers to tailor their gameplay experience to suit their preferences.

Modification example of Chinese Paladin (1995 Edition)

The pressing question is: why do game players, as subject, feel the need to modify games? Game modifications can generally be categorized into four scenarios:

- Game Difficulty Too High, Can’t Pass. This is the primary reason motivating most players to modify games. Game difficulty design has long been a challenge for developers. Titles like the arcade classic Ghosts ‘n Goblins (1985–) were notorious for their extreme difficulty, deterring players in the 1980s and 1990s. With the rise of computer emulators and PCs, these daunting challenges could be circumvented through game modifications. However, when modifications allow for excessive advantages, such as enabling one-hit kills against any enemy, including bosses, the game quickly loses its appeal. Game difficulty, especially the intricate challenges posed by bosses in terms of their attacks and defenses, is meticulously crafted by developers. Instantly defeating bosses diminishes the satisfaction of overcoming a genuine challenge, reducing the game to a mere clearance scene. Such modifications, particularly those facilitating one-hit kills, strip away the essence of games. The player-subject, reduced to merely mowing through levels, fails to engage with the intended strategy and intention of the game design. This reduces the game to a procedural experience focused solely on progression, devoid of the strategic thinking required by the original design. Essentially, excessive modifications that lower game difficulty not only diminish the authentic gaming experience but also erode the players’ inherent subjectivity. The game then becomes a pleasurable journey of advancing through levels, akin to watching a movie.

- Troublesomeness and Cumbersomeness. Many game designs, particularly early adventure games, were burdened with cumbersome mechanics. For instance, navigating a labyrinth required tedious backtracking through hordes of respawning monsters, diminishing the initial excitement of exploration and treasure discovery. Such gameplay becomes a time-consuming chore. In later game designs, teleportation mechanisms streamlined these mundane tasks. Early games lacked such conveniences, though certain items like teleportation scrolls in Heroes of Might and Magic (1995–) or teleportation charms in labyrinth-based games offered partial solutions. Players could modify their games to include numerous such items, optimizing gameplay flow and enhancing enjoyment.

PowerPak 286 running AutoCAD on MS-DOS. From a 1987 advertisement from Puget Sound Computer User for the PowerPak 286 IBM PC compatible, as sold by Evergreen Systems. Original photo taken by Dick Cruver of Star Productions.

© Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

- Hardware Limitations. Some early games, relative to the computers of their time, ran at a slower speed, causing characters to move across the screen like tortoises. This sluggish pace was often intolerable, leading to the development of early modification tools like FPE and Kingsoft Knight, which featured software acceleration to make the game faster and more engaging. In recent years, reverse speed control modifications have also emerged. When running a game from the 90s on a modern Windows system using a DOS emulator, the game often runs too fast. For instance, Xuan-Yuan Sword II (1994) from Softstar ran at a normal speed in its original DOS environment. However, over 30 years later, modern CPUs are dozens of times faster than those from the 90s. When running this game on today’s computers, Fu Ziche’s team moves at an excessive speed. Combined with the game’s battle strategy of random enemy encounters, this results in a non-stop monster-killing experience, detracting from the original gameplay. To address this, using modification software to reduce the speed to the original rate can help recreate the authentic experience of playing Xuan-Yuan Sword II as it was in Softstar’s heyday. Additionally, today’s advanced graphics technology has far surpassed the visuals of older games. Newer game modification software can enhance these old graphics, transforming the original pixelated interface into a more coherent and polished picture, something that was not possible in previous gaming eras.

Game interface of Xuan-Yuan Sword II (1994) from Softstar

- Mod. “Mod” is short for Modification. Essentially, it involves using the structure of the original game to create new content and scenes not present in the original design. To some extent, a modded game can even be considered a brand-new game. Modding shares similarities with the reasons mentioned in points 2 and 3: players with knowledge of backend programming and design skills use the original game’s structure to create their own content once the game is sold to them as a product. For example, Heroes of Jin Yong, developed by Soft-World’s Heluo Studio (later known as Oriental Algorithm System) in 1996, ambitiously incorporated 14 Jin Yong novels into one open world, which was a significant innovation at the time. However, due to design limitations, many popular plots from Jin Yong’s novels were not included. For instance, the growth of the hero Guo Jing, his encounters with Huang Rong, and their adventures were simplified into brief conversations on Peach Blossom Island. Years later, fellow gamers designed a game called Heroes of Jin Yong: Fighting Again (2006, published under the screen name Nangong Meng), based on the original. This mod not only significantly improved the graphics but also added many plot points omitted in the earlier version by Soft-World’s Heluo Studio. Another frequently mentioned modded game is Sangokushi Sōsōden (1998) by Koei Japan. With its user-friendly interface and wargame-like nature, Sangokushi Sōsōden serves as an excellent starting point for those interested in creating their own games. Over the following decade, different players used Sangokushi Sōsōden to modify titles like Legend of Zhao Yun and Legend of Jiang Wei from the same Three Kingdoms period. They also created wargames from different historical stages, such as Legend of the Heroes of Wagang, Legend of Yue Fei, and Legend of Resistance against Japanese Aggression. Among these modded works, some attain a high level of historical and textual accuracy, reaching considerable artistic standards. For example, Legend of Jiang Wei allows players unfamiliar with the second half of Romance of the Three Kingdoms to fully understand the story of Jiang Wei. As a great general of Shu, Jiang Wei resisted Guo Huai and Deng Ai on one front while contending with Huang Hao’s faction in Chengdu on the other, after Zhuge Liang’s immortal death in Wuzhangyuan.

From the reasons outlined for game modification, excluding the first point, all share a common thread: players do not view games as finished works but rather as continuously adaptable to suit their preferences. In this regard, players transcend mere consumption of gaming products to become active creators. Unlike movies or television shows, which are fixed and unchanging once released, video games are semi-finished works that require players’ participation. While players can adhere strictly to the game’s predefined rules as light players, such gameplay remains within the framework set by the game’s developers. Only through dark play and game modification can players truly personalize and imprint the game with their own lives. This transforms the game from a predefined experience to a canvas where players can inscribe their own narratives and choices. By setting their own scenes and battle strategies, players forge a unique symbiotic relationship with the game, turning it into a living entity that evolves alongside their interactions. The mission of dark play modification is to make the player-subject more attuned to the game, and to make the game more attuned to themselves. In Heidegger’s words, it is to make the game truly “ready-to-hand,” not to make the player-subject fit into a game that is external to them. The game that is ready-to-hand is the subject’s own game.

In his later lectures at the Collège de France, Michel Foucault delved into the hermeneutics of the subject, suggesting that individuals interpret their subjectivity through their own acts of creation—shaping not only their consciousness and behavior but also imprinting their environment with their influence. Similarly, in the realm of game modification, Foucault’s hermeneutics of the subject manifests as a hermeneutics of dark play, where the modified game bears the imprints of the subject. What we encounter in these games are not only the environments and scenarios crafted by the game developers but also the subject’s reinterpretation of the game through creative intervention. By reshaping the game, the subject establishes a new dynamic with the virtual environment, shaping how the game is experienced and serving as a source of entertainment. This process further unleashes the subject’s potential, enabling gamers to explore unprecedented realms and embody roles as darkwalkers in unseen dimensions of play. This interaction highlights human action’s boundless potentiality, showcasing how individuals can redefine their engagement with virtual worlds.

The French philosopher Bernard Stiegler once proposed that technology acts as a prosthesis for humans, linking our perceptions to a world inaccessible to our bodies. This changes the subject’s situation, expands their horizons, and allows them to face a broader world. Games can also be seen as a prosthetic world. Instead of perceiving the unknown physical world through material tools, we use gamified characters to navigate a digital, virtualized space. In this realm, everything becomes interconnected under the virtual prosthesis, necessitating Stiegler’s concept of organology. The material world we inhabit is limited, and both bodily and prosthetic perception can only display our imagination within a three-dimensional continuum of space and time. However, video games, especially those modified through dark play, offer the subject the ability to alter the world according to their understanding. This reflects the notion that everything in the world becomes an organ for perceiving the future. These organ worlds form a customized space centered around the player, embodying the concept of organology. The dark play-modified world of organs does not aim to make the world submit to the subject’s dictates but to create a harmonious symbiotic relationship between the subject and the modified game environment. This dark play game world significantly extends human reach, allowing us to perceive spaces that do not exist. For example, Atomic Heart (2023), developed by Mundfish in Russia, enables us to experience life and interaction in a utopian world that combines high mechanization with Soviet socialism, offering a perspective distinct from our own reality. However, the world of Atomic Heart is still designed by the game company, and we remain bound by various environmental constraints. With gameplay modifications, the setting of Atomic Heart could become more personalized, transforming into a customized game space. Through dark play modification, we might realize the true essence of gaming: playing is not merely about following game rules or indulging desires. It involves creating an organological world of one’s own. In this organological world, where the self encounters an undescended world, we understand that the game serves as a hermeneutic device for the subject—the subject reinterprets the game, and the game regenerates the subject.

Lan Jiang, born in September 1977 in Jingzhou, Hubei Province, is a professor in the Department of Philosophy at Nanjing University and a doctoral advisor. His primary research interests include overseas Marxism, contemporary radical leftist thought in continental Europe, and digital capitalism. His major publications include How to Think about Global Digital Capitalism? (2024); General Data, Virtual Bodies, and Digital Capital (2022); and Loyal to Event: Introduction to Alain Badiou’s Philosophy (2018). He has also translated works by Agamben, Badiou, and others, including The Kingdom and the Glory; What is Philosophy?; Being and Event; and Logics of Worlds: Being and Event II.

Translated by You Yiyi