ALEX KATZ

| July 27, 2011 | Post In LEAP 9

It’s an easy mistake, for those of us who came to contemporary art by way of China, to think that a big face painting is a big face painting. From Luo Zhongli’s coining of the genre with his penwielding peasant Father, to Geng Jianyi’s analytical innovation on the form in 1988 with his monotone “Second State” series, and on through the excesses of the 1990s as the bald men came to swallow an entire field of semiotic possibility, this is fraught terrain. Alex Katz is one of the key references drawn upon by this strand of Chinese painting as it grew up. When, at the Pace Beijing opening show “Dialogue” back in 2008, a wan Qi Zhilong hung across from a Katz, certain elements of the New York-Beijing axis felt vindicated. More than any other pairing in that show, this one spoke to the kind of arrival the scene and its protagonists had been craving.

Of course this has nothing to do with Alex Katz himself, which is why this exquisite little show deep in a Shanghai lane was so poignant. In the converted domestic space of James Cohan Gallery Shanghai hung five single-figure paintings and six arboreal prints; in a glass-topped display case in the sunroom, a portfolio of seven leaves rounded out the presentation. The impression was of calm and refinement, and of the exertion necessary to create this kind of a space amidst the clamor.

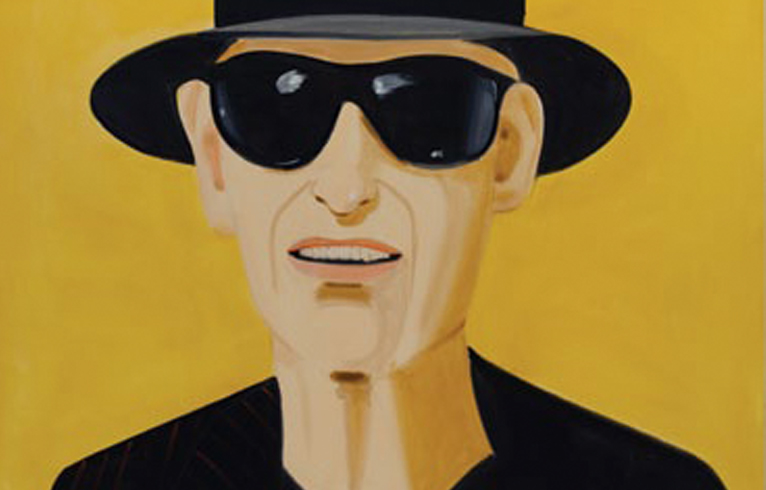

First, the paintings: Alex in a fedora and sunglasses, looking from a side wall at the show which he was unable to personally attend. In the next room, his wife, the stately Ada, in a green frock against a background of green leaves, linking the people in the show to the nature. Then: Three cold Scandinavians, Anika, Tara, and Ulla, barren faces on empty backgrounds, one black, two blue. This makeshift grouping interacted with each other from across the rooms, characters in a silent film. When Arthur Solway, the gallery director who curated the show, led me through, he referred to the paintings by their names— also the names of the sitters— as if they were living creatures, old friends.

For all their graphic power, the thrust of a Katz painting lies in the fragility of its distinct components; up close, one learns the retrospectively obvious lesson that what looks like a face is but a set of strokes, each one nearly transparent. The simplest twists of the brush define entire facial contours; a nose grows from a flick of the wrist. As his friend Willem de Kooning apparently once said, Katz’s paintings “are like photographs, except they’re not.” The prints, on the other hand, expose a set of formal concerns that border on abstraction: in Twilight, for example, the same shadowy tree is rendered against changing color and light. In this combination of works, we get the sense of Katz as an artist who works less with a bank of images than with a set of linguistic structures.

In a catalogue essay titled “Shades,” Merlin James talks about Katz’s work in terms of a cool that transcends time, lingering archetypally like the images of MacArthur landing in the Philippines wearing Ray-Bans during World War II. The timeless cool is of course a weighted notion, a product of mid-century American supremacy, and these are different times. What would it even mean to be dated in a moment, and a place, where temporality has become so thoroughly disjointed? Nevertheless Katz, who graduated from Cooper Union the year the People’s Republic was founded, resonates here— not because he has been meaningfully imitated on a formal level, but because his aesthetic horizon of bearing witness to interesting times, and distilling them into images that persist without monumentalizing, that know how to be smart without being conceptual, seems to many Chinese painters like a pretty good thing to aim for. Philip Tinari