HILLA BECHER

| July 10, 2012 | Post In LEAP 15

Born in Berlin in 1934, Hilla Becher first started collaborating with Bernd Becher in 1959, taking photographs of the water towers, blast furnaces, cooling towers, and other industrial structures that are legacies of Germany’s industrial era. Cataloging them according to type, Hilla and Bernd became pioneers of the field of industrial photography. In the years her husband was teaching at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, he influenced many of the artists that later made a name for themselves in the photography world, such as Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff, Jörg Sasse, and Andreas Gursky, known by art historians as the “Düsseldorf School.”

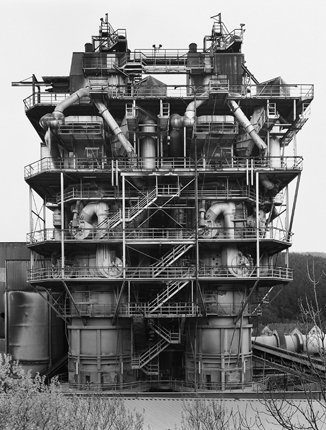

Hilla Becher We also had the same issue. At the very beginning, I was particularly interested in the blast furnace smelting metal in the steel mill, as its structure was completely different from any other building structure. I remember telling my husband once: “This architecture is just too confusing, we simply have no way to shoot it.” So we decided to climb quite high up, and as we climbed onto the opposite blast furnace, we looked down from above, and were able to observe the direction of the structure and the pipelines, which looked just like a primitive forest. They could only be fully observed after climbing quite high. If we had not done that, we would have only had one shot from below (although we tried very hard to only take one picture). The same approach ought to be used when shooting other objects. For a hoisting derrick, in order to have a more complete effect, first you shoot its top part, then its lower part.

LEAP What is the difference between climbing high to see a single industrial building or an industrial landscape, and climbing high in a forest to see its natural scenery?

HB The climbing process is very different. When climbing a blast furnace or a hoisting frame, you do not use steps, but a ladder, and usually you need to zigzag your way up. Interestingly, when we talked to the factory workers, even though they had not received any photography or professional training, they could tell you quite distinctly which part you needed to climb if you wanted to capture a specific image.

LEAP The industrial architecture photographed by you and your husband displays man’s power and imagination in the industrial age, the physical form of a spirit. Are objects or buildings able to represent the spirit of our times today?

HB Computers are worthy representatives of this era. But there is no doubt that in the nineteenth century and, in part of the twentieth, industrial architecture, ships, airplanes… and everything that was related to modern society, were the most iconic proof of human inventiveness and creativity. To a certain extent, we could say that it all started with mining, and with those other heavy industries that triggered the Great Leap Forward of human history. But now people are rarely able to see this kind of architecture, and if they lack visual experience, they may just find it ugly, hard to like and understand. We wanted to compensate for this on our shoots and capture the objects as simply and clearly as possible.

LEAP Indeed, sometimes I feel that the industrial buildings of your photos seem nearly human, with a face, a body, legs.

HB Your feeling is particularly accurate. We found those blast furnaces and hoisting frames especially full of life. People often compare men to machines, but it might be more accurate to compare machines to men. A blast furnace, for instance, is a body that, because of its heat, does not have skin. But it also reminds us of other animals or botanical plants; in order to increase its functionality, it expands its pipelines, and is changing constantly. Some blast furnaces are already over 100 years old, but their material is relentlessly renewed and transformed, just like the metabolism of a biological cell.

LEAP I am also interested in the preservation of post-industrial buildings. For instance, you once shot the Zollern coalmines in Essen (Zollverein in Essen), which have now become a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as well as the stylish buildings designed by SANAA (architecture firm headed by Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa). Would you visit these “post-industrial” buildings again? How do you regard the “life” of these structures?

HB I often visit these sites. In the Ruhr area, we have participated in the movement for architectural preservation, while in smaller areas, we have engaged in community activities in the hopes of being able to preserve some of these buildings and structures, such as a single relatively high hoisting derrick for example, and to remember the others that have been torn down. This also depends on the inclination of local people and governments, as the derrick itself is made of metal: if sold as scrap iron, it could become a source of income. If this was worth DEM 1,000 before, it could be worth EUR 1,000 now. In the Ruhr, about 95% of industrial installations have already been torn down. I am quite sad about this, as once these structures are dismantled, they simply disappear, leaving no trace of their former existence. But when we look at this issue, we also have to be rational. When an industrial building is of no more use, it has to disappear, as it is unlikely that it will ever have the eternal state of preservation of pyramids. New buildings will always keep appearing.

LEAP A rather sensitive issue is that the phenomena of Germany’s post-industrialization has meant the arrival of a great number of German companies in China, such as the BASF chemical factory in Nanjing, or Volkswagen’s recent decision to invest in an automobile production line with an annual production of 50,000 units in Xinjiang. What do you think of the “migration of capital and production” taking place in today’s world?

HB The nineteenth century presented a similar situation, with the British owning shares in Germany’s companies, and Friedrich Engels establishing a factory in Manchester. We still have a lot of interest in this, as we have observed in Hagen, Luxembourg. Once, a group of over 100 Chinese people arrived in Germany and bought an abandoned blast furnace. They sketched its design, and took every piece of metal in the structure back to China. Upon their return home, they rebuilt a new blast furnace following the exact same model of the original.

LEAP Last year, your husband’s former student Andreas Gursky sold a large-scale color photograph for EUR 550,000 in Hong Kong, a price much higher than a lot of paintings. Why do these photography works receive people’s recognition?

HB He was not responsible for that! If everyone wants to own a certain picture, then that picture can become particularly expensive. This is what the market leads to. (Translated by Marianna Cerini)