GWANGJU BIENNALE 2010: 10,000 LIVES

| October 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 5

The eighth edition of the Gwangju Biennale was, in artistic director Massimiliano Gioni’s words, an “anthology of portraits” and “a show of faces and eyes.” Based on a simple conceit—that humans make images to stymie the flow of time, and having made them, do strange things in their service—it offered a bulky compilation of pictures in an attempt, knowingly doomed, to face off against the digital flow of the shutter-happy world at large.

Gioni took his narrative cue from a sprawling literary work, Ko Un’s encyclopedic poem Maninbo or 10,000 Lives, a title that of course worked so much better in Korean than in English translation. He took pains to explain how “man” means not just 10,000 but “all,” “in” not just life but “humanity,” and “bo” an album or register, something entirely missing from the English. As a naming gesture, it was polite, referring in an intelligent way to a textual product of the Korean democracy movement: Ko Un, an anti-authoritarian activist, began the poem while in solitary confinement, protesting madness and forgetting by mentally compiling portraits of every person he ever met. This titular work conveys, in its sheer volume (or volumes—30 to be precise) both the bulk and the eclecticism Gioni sought to embrace; Ko Un, we are reminded repeatedly, included literary and historical figures among his poetic subjects, much as the exhibition includes cultural artifacts and found images in addition to works of art.

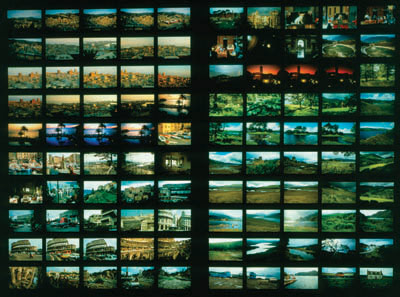

The notion of the “bo,” or “pu” in Chinese, is key to the whole enterprise. This character, defined as “a volume which sorts objects according to type or properties” could have applied to at least half of the works on view. The cover piece, is an ensemble of yearly, posed studio portraits of Beijing merchant Ye Jinglü, which follow his rake’s progress from a Westward-looking employee of the Chinese ambassador to the U.K. in the waning days of the Qing through a harrowed death in 1968. Ye’s young self adorns the front of the catalogue cover, his wizened visage peers out from the back. This aesthetic logic of a sprawling, trans-temporal image collection project with some sort of basic underlying principle underlay many of the works on view. Pieces such as Fischli /Weiss’s twenty-eight-meter long table of travel photographs collected over fifteen years, Philip-Lorca DiCorcia’s visually rhyming Thousand Polaroids, Hans-Peter Feldmann’s exhaustive compilation of 9/12/2001 front pages, and Ydessa Hendeles’s three thousand-strong library of early-twentieth-century Teddy bear photographs followed suit, among many others.

The line through the exhibition was clear to the point of benevolent dictatorship, moving straight through the four identically proportioned galleries that comprise Biennale Hall with only one way forward. The first looked at how humans pose for cameras, with pieces like Mike Disfarmer’s penny portraits from 1940s Arkansas, E.Q. Bellocq’s defaced photos of New Orleans prostitutes, Arnoud Holleman’s appropriated 1960s film footage of Dutch protestant villagers shielding themselves from the camera’s gaze. The second queried the retinal mechanics of viewing, an exercise that began with visual tricksters like Stan Vanderbeek and Paul Sharits, but quickly moved to more socially implicated works, like Seth Price’s meditation on the digital transmission of Daniel Pearl’s beheading, or a piece by Harun Farocki which documents the process by which American soldiers returning from Iraq are treated for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder using a virtual-reality contraption in which they are allowed to relive, through meticulously fabricated images and under psychiatric guidance, their moment of near-death.

The third gallery was where the show really hit its stride, examining the process by which images become symbols loaded with political and historical baggage. This route through this hall began with the 103 figures of a recently cast copper-plated fiberglass edition of the Rent Collection Courtyard (borrowed from the Sichuan Institute of Fine Arts and implicitly responding to Harald Szeemann’s well-known unrealized project of including this epic cycle in his 1972 Documenta) and proceeded to Byungsoo Choi’s oversized portrait of student-movement martyr Lee Han-yeol—the image around which the country’s reformers rallied in 1987, mounted on a truck like the one that carried his body from Seoul back to Gwangju, and showing from behind the scars of knife wounds inflicted on the image by police. Diversions through works such as Rabih Mroué’s study of Che Guevara’s famous death portrait and journalistic images like Paul Fusco’s lyrical photographs, seemingly staged, from aboard the train bearing Robert Kennedy’s slain body, intervene. The gallery crescendoed in the juxtaposition of Gu Dexin and Carl Andre, the former’s text panels bearing simple sentences of the “We have killed/We have eaten” variety echoing, in their slippage toward abstraction, off the latter’s privileged Minimalism. Turning a corner, the viewer finds himself in a room of Tuol Sleng prison photographs, pre-execution portraits from the height of the Khmer Rouge terror, with their own complex status in contemporary art history since being shown at MoMA in 1997.

The fourth gallery went on to look at iconic, totemic objects, bookending a salon-style restaging of Mike Kelley’s 1993 exhibition “The Uncanny” with Korean Kokdu funereal dolls and a gallery that juxtaposed a giant Maurizio Cattelan crucifix with Tino Sehgal’s first single-dancer performance, which explicitly forbids documentation even as it includes a moment in which the dancer pretends to snap a picture of the viewer. Two nearby side venues seemed to function as receptacles for that which, for reasons of space or concept, could not quite fit into the main hall, even if the interesting juxtapositions—as between Ryan Trecartin and Cindy Sherman—persisted. The full installation of Tehching Hsieh’s timecard-punching performance, in which hourly snapshots of the artist papered an entire room, drove home the entire conceit of the exhibition.

Like Okwui Enwezor’s in the last edition of the biennale, Gioni’s China selections were offbeat and interesting, and argue that this national context has been normalized after years of country-targeted inclusion in major international shows. In addition to the pieces already mentioned, contributions from Guo Fengyi, Kan Xuan, Liu Wei the Middle, Liu Zheng, Wu Wenguang, Zhang Enli, and Zhou Xiaohu fit into distinct places within the narrative. Gioni’s ecumenism is admirable; the only regional voices truly absent were those of Taiwan (a strange omission given the oft-invoked comparison between the Taiwanese and South Korean models) and North Korea. This lacuna owes to longstanding restrictions on presenting anything from the North enforced by the Ministry of Unification, in a confirmation that for all the rhetoric of democracy and openness of which the Biennale is a celebration and commemoration, and despite the proliferation of images and viewpoints on which this edition is themed, some images remain truly off-limits. Philip Tinari