TALLUR L.N.: CHROMATOPHOBIA

| October 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 5

Tallur L.N.’s sculptures are depressive fantasies of systems beyond individual control; they depict humanity as commiserating victims of a world too large and too alien to do anything but become overwhelmed by. The artist’s recent outing at Arario Gallery’s Liquor Factory outpost, “Chromatophobia: The Fear of Money,” meaning a persistent fear of money, distills the malcontents of an economy bent on not behaving into a series of works that become visual manifestations of our currency phobia and fetish; its power to overwhelm and undermine us.

Money is frightening on an intimate and an individual scale: the threat of its loss, the prospect of its gain, and the intimidating personal competition over who possesses the most looms large over much of our daily lives. But lately, money has been terrifying on a much larger scale: money doesn’t slip out of pockets or off year-end bonuses, it ebbs in epic tides that leave foreclosed homes, empty office buildings, and millions jobless in its wake. Within the context of this massive sea change and the brand new world of the economic crash, Tallur L.N.’s sculptures represent the detritus left stranded on the beach as the water flowed back to sea. Like our currency, the machines Tallur has created no longer work as they should, and the initial promise of their functionality is lost to the hopelessness at their failure to really do us any good.

“Chromatophobia” is separated into two gallery spaces, and the two spaces also split into two conceptual themes. The front gallery’s three works stand attendant as icons, appropriating the visual language of Hindu religious art and its signifiers of enduring mystery and spiritual resolve. In the center of the space, the abdomen of an enormous tree is speared on a fulcrum of twin bronzed figures; a seesaw with one end on the ground. The tree’s surface is peppered with coins affixed to the wood by thin nails; hammers on the floor lay as evidence to the action. Part exorcism, part participatory baptism, the work invites us to banish the evils of money from our lives and minds through the sacrifice of coins to the wood. On another side of the gallery, wood inlay wall pieces meditatively mimic the rings of a growing tree, seen in cross section. The hopeful quality of nature and the organic in this initial showing plays against the resolutely inorganic works in the exhibition’s second space.

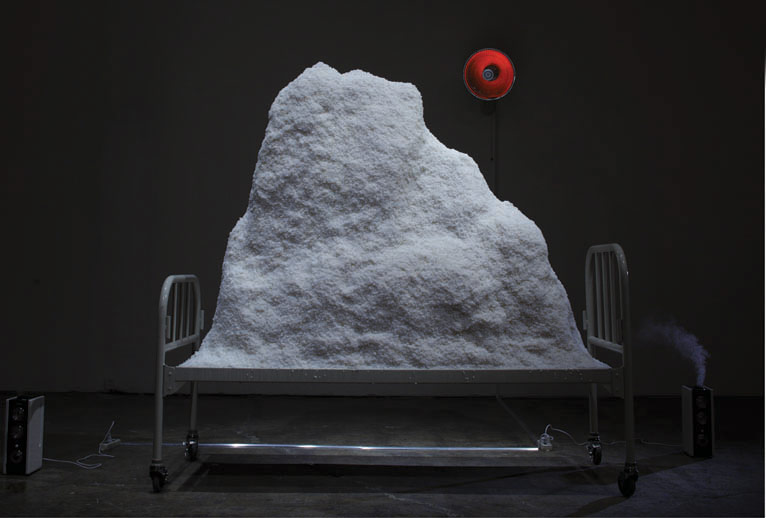

Tallur’s second gallery rattles. Apocalypse is the one machine in “Chromatophobia” that works. A rotating magnetic field drags a swath of nails over flipping coins, scratching the currency bare of all its defining markings. Thus cleansed, the coin is displayed as “civilized.” The situation gets more desperate after that. Tallur’s remaining works are half-broken artifacts of the money economy, a massage chair like a prone human body below a claw crane, all enveloped in white tar. Feed money in to make the claw move and grab at the absent figure. A mammoth conveyor belt and funnel system digests itself apart. A mountain of silicon rice mounds blankly on a hospital gurney, attended to by two heat-lamp nurses. Everything is false and weird. The works feel yucky, and repulsion is often a stronger emotion than anger or pleasure.

Money is a hedge against chaos, a human construction that provides a failed illusion of safety and stability. Tallur makes its inevitable betrayal visible in his failed talismans that in turns pray for redemption and give themselves up to their own death. The range of this thrashing between active struggle and passive acceptance of failure is physically present in Lamp (deepa sundari), another pair of bronzed figures set facing one another. Yet somewhere around their torsos, the contraposto bodies become enveloped in lumpy, rock-like cement. Where the two statues would meet, the rocky outgrowths go flat, a sharp, mechanic cut that leaves them inches apart. Half organic form and half inorganic tumor, Lamp seems to represent the immobilizing curse of greed. Kyle Chayka