Possible Friendships

| March 9, 2022

In artistic collaborations, the friendship within can make a more memorable work than the work itself. It transcends the singular figure of a creative subject, deriving its existence and meaning from the schism between two individuals. A work that commemorates a late friend becomes a dialogue that traverses time and space, in which the artist traces and honors the memory of the friend being represented; a form of reparation for the void, a solace to the self. How do we take one step back in the creative process, to better recognize, and live with, the other? And to extend our imaginations farther, even? Works emerged from friendships offer a manifold of clues for unpacking the forms of friendship and its endless possibilities.

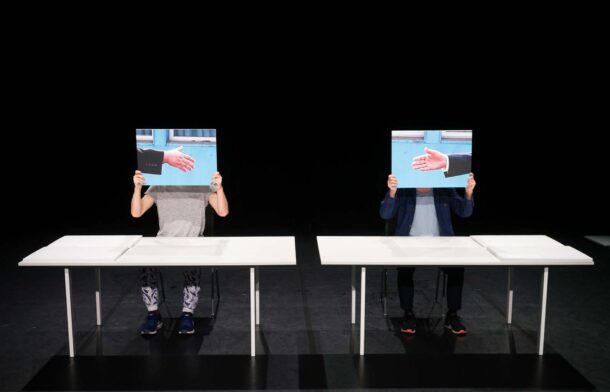

Jun Yang🤝Michikazu Matsune, The Past is a Foreign Country, 2018

Photo: Elsa Okazaki

Why Not Do It Together

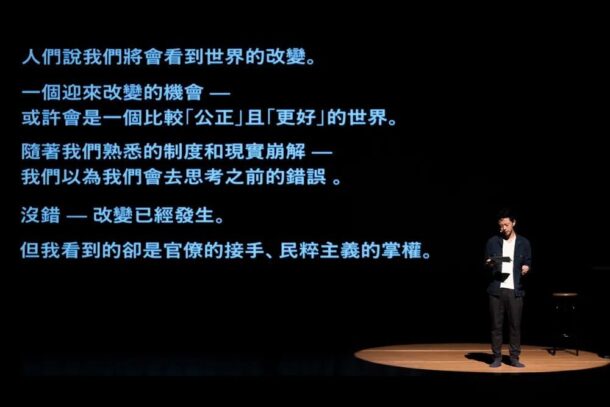

Somewhere in Taipei, the performance of Dear Friend (2020), a collaboration between Jun Yang and Michikazu Matsune, began with Yang standing alone on the theater stage, lit by a gentle stroke of light. Joined by Matsune–based in Austria, he couldn’t make it to the performance in person–via a video call, two artists recited the letters they exchanged during the post-travel quarantine periods. In calm and sincere voices, they talked to each other and the audience: “What, really, is this time that we inhabit? Travel restrictions, city lockdowns, no parades. Borders and walls were resurrected. The ocean, once again, set us apart. […] I looked up at the sky and not one plane flew by. The sky must be enjoying this moment of peace. Or did it ever miss the days in planes’ company? […] I want to hug someone and look straight at their face; to breathe their breath and smell their smells — even on a scorching, humid day. A world where I can actually raise a toast with you, my friend!”

Jun Yang🤝Michikazu Matsune, Dear Friend, 2020

Taipei Arts Festival 2020, Zhongshan Hall Theatre Taipei

©️Taipei Performing Arts Center

Photo: Tsai Yao-Cheng

What these heartwarming letters bring forth is no stranger to any of us. In Yang and Matsune’s personal stories and their perceptions of a world being shifted by COVID, we see a deep, border-crossing bond between two friends, as they navigate the post-pandemic age. And we get a reminder, too: the world the artists aspire to, where one feels at home anywhere, where one could joyously announce “a toast with friends” to the screen, is no longer the same.

Dear Friend gently unfolds the friendship between the artists, while making a curious reference to their previous collaboration project, The Past is a Foreign Country (2018). Based on the structures of Kamishibai, a traditional Japanese storytelling technique, the lecture performance alternates between personal accounts and historical events, recounted by the two artists-brothers-doppelgangers, each with a complex identity background. The work finds an at-once humorous and critical way to address the moments of rivalries, grudges and compromises among three NASA astronauts during the 1969 moon landing; the meeting of North and South Korean leaders at a 2018 summit, aired on TV and brimming with performativity; the anecdotes of the first climbers who reached the top of Mount Everest; the controversies sparked by border conflicts and immigration policies in Asian history.

In The Past, the construction of national history and the definition of collective time, which can be moved and removed (how the North and South Korean brothers created a unified time zone), are presented as an atomized formation of perceptions and memory, stretched across the long course of personal history. Whereas in the more recent Dear, a healthy man, forced into quarantine, is unable to take the “one small step” to leave their room. In our present world, the small attempt to form a more intimate interpersonal connection bears nonetheless greater difficulty, than the “one giant leap” that marks mankind’s foray into the unknown in The Past.

Jun Yang🤝Michikazu Matsune, The Past is a Foreign Country, 2018

Photo: Elsa Okazaki

Who Would Go First?

A formless tie, friendship makes the reconnection of possible worlds. For Jun Yang, making works is usually inseparable from collaborations with friends, interspersed with a playful joke or two. The captivating quality of the two works lies in the fact that they are simultaneously about the reality’s trial on friendship, as it goes through the process of artistic collaboration, and about collaboration and friendship itself. In the making of The Past, to figure out their plans, Yang and Matsune chose to mandatorily stay in “quarantine” together, which yet fermented frustrations — the irresolvable individuality of an artist had been stifling. During the three weeks of isolation, they were not unlike the three astronauts (Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins) stuck in the metal cabin, struggling through and tortured by mutual tolerances, vexations, compromises and reconciliations. Indeed they had completed a mission impossible, yet the sense of loss and emptiness lingers on.

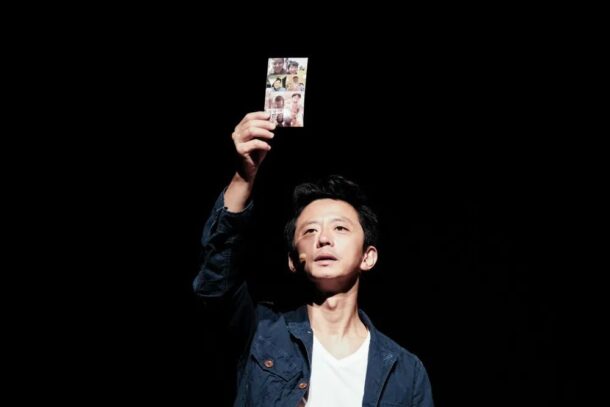

Hito Steyerl, November, 2004

DV, single channel, sound, 25 min

If the runner-up is the biggest loser, then who is the first? Who wins? Who is the hero to be seen and known? Sometimes we even witness how competitions between friends turn friendships into jealousy and estrangement. The discrepancy in opinions, the never-ending arguments — figuring out a work that speaks to both, and is recognized by both, is an extremely hard task. It is because “being friends and being collaborators are two different matters,” despite “we’ve been friends for this long.” The tension between Yang and Matsune mirrors the dynamics of several protagonists who take the stage in their work. On one hand, their collaboration comes from the premise that they must produce a work together; on the other hand, it is rooted in their long-standing friendship over the years, which concerns “ways in which we can come together outside of the shadows of ourselves”. Matsune’s physical absence from the stage takes away certain experiences, encounters and conversations from the performance, rendering a shared experience and existence a lasting regret. Towards the end of Dear, Matsune promises that they will meet soon — I’ll go first, while the performance goes on. A hint of melancholy haunts the seemingly cheerful farewell, as if it is a compensation for emotions.

Hito Steyerl, November, 2004

DV, single channel, sound, 25 min

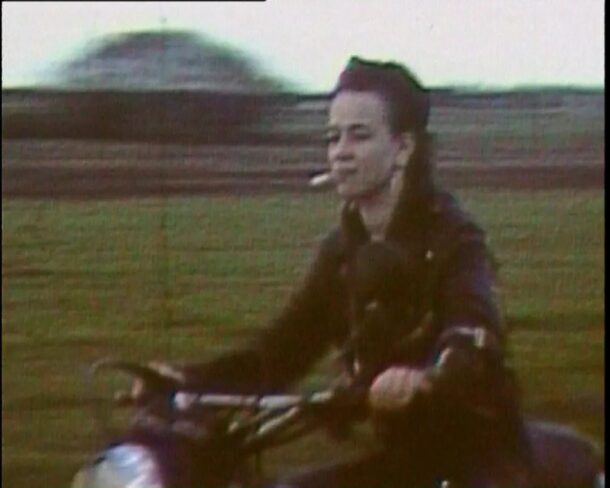

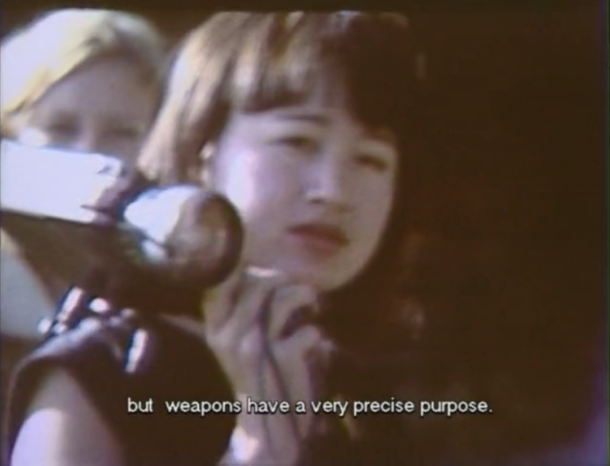

Of two friends, one is likely to go first. In Politics of Friendship, Derrida posits that friendship hinges on the very possibility that one friend will leave before the other (even passing away right before his eyes). How to represent and remember a passed friend in a work of art? Hito Steyerl’s Super 8mm film November (2004) departs from the death of her friend Andrea Wolf, a Kurdistan Workers’ Party militant, who, in 1998, was killed as a terrorist in Turkey’s Eastern Anatolia Region. Lacing together documentary footage, personal archive, news stocks and the artist’s own narratives, Steyerl produces a film of and about images. Besides the overflowing camaraderie that emerged from and solidified by Steyerl and Wolf’s common beliefs in feminist endeavors, we see in the film a funny but heartfelt eulogy, a deep remembrance. Steyerl portrays her female friend as a sassy, one-of-a-kind icon of her time: mysterious and invincible like Bruce Lee, she appears in news interviews as an amicable warrior, always carrying a gracious smile — the same smile has been emblazoned on the Kurdish flags after her passing, forever remembering her as a martyr. During Wolf’s memorial procession, Steyerl bid farewell to her friend, sacred as if attending a funeral rite. As Derrida writes, “The death of another person—and especially when we love that person—in no way signifies an absence, disappearance, or some kind of end of life. […] Death announces the end of a whole world each time (the end of a possible whole world, the end of a unique and whole world each time), and is, therefore, both irreplaceable and infinite.” In the final sequence of the film, in the artist’s imagination (and throughout the haunting memories), her friend picks up the pistol from the ground, as righteous as a Western film protagonist. She shoots the bad guy who just killed her comrade (“me”) with such ease and gallantry, riding away on her motorcycle in the setting sun. The friend becomes the captain of my spirit, while fiction and reality, past and present, are just like a pair of friends who see themselves in each other. How wonderful would it be, if, instead of you, it was “me” who died!

Hito Steyerl, November, 2004

DV, single channel, sound, 25 min

If I Were You

If to miss someone means to recognize their absence, friendship is perhaps an affirmation of this very void. In a world where its intrinsic ties with the rather pure friendship are shaking in precarity, whether it’s possible for creative subjects to create with a critically withheld intrusiveness on their part? Perhaps, distance does not indicate the act of distancing, or a lack of perspective thereof, but a removal, out of respect, from one’s temptation to impose control over the other in terms of knowledge or understanding. “[I]t is the interval, the pure interval that, from me to this other who is a friend, measures all that is between us, the interruption of being that never authorizes me to use him, or my knowledge of him,” writes Blanchot in his essay “Friendship.”[1] For him, friendship exists beyond the public realm and within a highly intimate and private sphere, characteristic of its self-negation—it is the fragility of things passed that declares it. In this way, writing or artistic practices should relinquish from any intents of control or directorial attempts, and instead posit themselves as an exercise detached from knowledge. The unknown friend shields friendship from power.

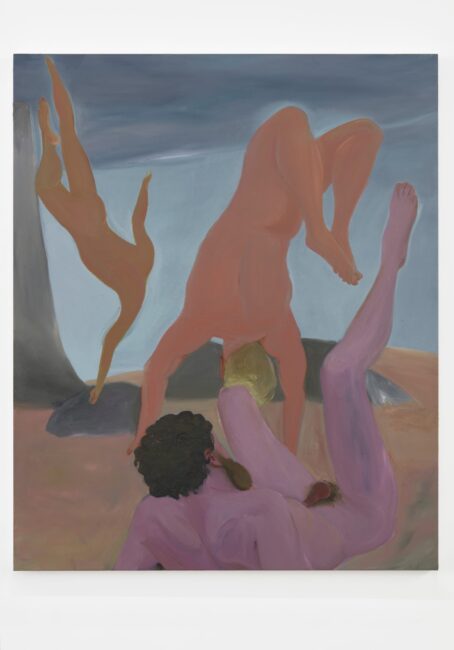

Cheng Xinyi, I Surrender…, 2018

Oil on linen, 140 x 115 cm

How does an artist portray someone in their unfamiliarity, then? In Cheng Xinyi’s paintings (and her real-life connections with her painted subjects), we can sometimes catch a glimpse of such proper distances. There are more “him/her/it/them” than the triad of figures — in real life, in imaginations and in representations. The artist befriends with whom she paints, some close and some distant. A moderate silence, whether or not this level of moderateness implies a Dorian Gray-esque projection and transference. In I surrender… (2018), three elegant males dance in an empty mountain forest like goddesses, infusing the space with ethereal, soft yet powerful beauty. The image is reminiscent of Pasolini’s portrayal of a beautiful friendship – the young men in their twenties gather together, their voices of innocence intact from the world around them; they go on their ways of living, filling the dark night with their cries. Their masculinities, and everything intrinsic about them, turn into waves of laughter.[2] In fact, Cheng has abstained from enforcing the ascribed identities of her subjects onto the canvas: by separating the painted bodies from the strongly implicit social contexts, Cheng prevents the risk of objectification. In “loosening” the grip of concepts upon things, it becomes possible to relate. In an interview titled “Friendship as a Way of Life,” Foucault brings up the problem with the relationship between two men, which does not necessarily lie in the uncovering of their sexualities, nor in their violation of societal norms in certain conducts. In fact, the “problem” that the current institutions fail to understand and accept is the multiplicity of relationships that we manage to arrive at, where no system of codes is capable of disciplining us anymore.

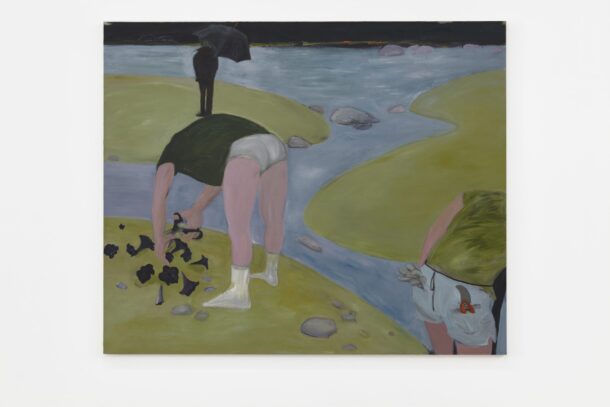

Cheng Xinyi, Swimmers, 2021

Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm

Cheng Xinyi, Crossing II, 2019

Oil on canvas, 90 x 105 cm

Left: Cheng Xinyi, A Whip, 2018, Oil on canvas, 150 x 125 cm

Right: Cheng Xinyi, Parapetto, 2021, Oil on canvas, 160 x 145 cm

What can this recognition of distance inspire? Can we unleash our imaginations further on the basis of such a relationship, in critical ways? In his novel Hate: A Romance (La meilleure part des hommes, 2008), Tristan Garcia touches on a snippet of history he didn’t live: the stories of gay men living in Le Marais, Paris, during the 1980s AIDS epidemic, turning it into an autobiographical fiction narrated in first person. Upon first glance, the writing might fall short of certain morals and empathy. However, by writing about a time virtually impossible to personally access, Garcia’s real intention is to turn down the authors’ usual impulse of transforming their lived experience into fiction, thereby dodging its drawbacks. To inhabit a time, a sexuality and a community (identity) he does not belong, is to return to the original state of writing, which is but a genuine embracement of fiction and imagination. Through the writing of fiction, or rather, a “rational enchantment”, the author’s chief task is to know themselves, by way of others. I am only known to “me” in others’ knowledge of “me,” not in the creases of an enclosed individuality I fold myself into, where the entrance to my experiences is only left open for no one but me. Garcia continues this endeavor in his later novel, Memories of the Jungle (Mémoires de la Jungle,2010), where he goes as far as forsaking the voices of humans. In announcing our language to gorillas, the most human-like non-human species, there is an effort to outline a world beyond ourselves.

Cheng Xinyi, Song for the gardener, the monk and the poet, 2017

Oil on linen, 165 x 200 cm

Yan Fang is a curator at UCCA, as well as a writer. She currently lives in Shanghai.

Translated by Sixing Xu

________________________________________

[1] Maurice Blanchot, “Friendship,” in Friendship (Standford, California: Standford University Press, 1987), translated by Elizabeth Rottenberg, pp. 291.

[2] P.P. Pasolini, Lettere 1940-1954, 1986, pp. 36.