Don’t Kill Me, I’m in Love! — A Tribute to Huang Xiaopeng

| March 28, 2022

Huang Xiaopeng, Le Probleme Est Une Economie Du Stupide! (detail), 2015, Installation (plastic houseware and toys)

Exhibition version reproduced by Zhao Baochen

I knew very little about the artist Huang Xiaopeng (1960-2020), as for many young people who only recently returned to China. The retrospective and tribute exhibition at Times Museum thus constituted everything I could get to know about him. There will be no over-interpretations, only a portrait of the artist that I gleaned from all the works exhibited. Portraits of artists are often the most moving in art history. Artworks can be over-interpreted by critics, whereas the artist’s persona is something every human can relate to.

The exhibition begins with a sketch of Soviet realist style by Huang Xiaopeng during his youthful years at Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, showing his disciplinary training at the beginning of his artistic career. However, judging from the works presented in the exhibition, rather than exploring the techniques, the young artist seemed to manage to develop different aesthetic possibilities of the image of workers. What exactly is “realism”? Does it refer to a realistic portrayal, an aesthetic examination, or a re-imagining of working-class life? The questions that Huang posed remained unanswered during his short time at the Academy. He constantly bounced back and forth between various styles of experimentation when the subjects of portrayal were almost fixed.

View of DON’T KILL ME I’M IN LOVE! —A Tribute to Huang Xiaopeng, Guangdong Times Museum, 2021

Shown in photo are (from left to right) Playing Cards (1996), Untitled (1991), and Untitled (1991).

Huang Xiaopeng’s collage works in the 1990s, with a strong structuralist overtone, seem to suggest a completely different way of thinking than before, and the topics of the times including the Gulf War, and multicultural identity began to recur in his works. How does one digest the news of social reality and the visual language in painting, and mix the Western environment with a Chinese cultural context? How does an artist, as an individual, deal with parallel yet distinct cultural value systems? These were the contradictions that he had to consider. In the collage Untitled (1991), a gloomy patch of black color is surrounded by newspaper headlines, reflecting the clear divide between the artist’s inner activities and the outside world. At the time, Huang was studying at the MFA program at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. His accumulated experience of realist painting prior was not necessarily understood, and was even further blurred by his Chinese identity. He attempted to present the absurdities and unsympathetic aspects caused by cultural conflict by a disorderly collage of textures and materials. In another Untitled (1991), the black oval in the center of the picture opens up in the middle and the translucent plastic wrapping paper from an art shop is also hollowed out from the center and revealing four playing cards. Such a composition shows new ways of constructing meaning in the collage of symbols, numbers, messages, and abstract forms. The black color is pushed to the edge, while the set of cards in the image introduce an independent system of numerical and symbolic combinations. The artist’s treatment of the symbols seems to be parallel to the multicultural system; at the same time, he overlays the language of abstract painting with the semantic system of the readymade products, subtly blending the conflict between art and life itself into the composition and the translucent layers of materials, allowing the viewer to shift between different semantic systems in order to interpret the paintings. The contrast between the two collages, which are both named Untitled (1991), illustrates the artist’s mental transformation, while the playing card, as an independent dual system, becomes an archetype for his later reflections on individual existence.

Du Zhongjian, Break, 2021, performance, installation (glass mirror, photos, hammer, stones, broom, stovel), 235 x 135 cm.

On the wall is a photo of Huang Xiaopeng’s Security Glass (1992).

View of DON’T KILL ME I’M IN LOVE!—A Tribute to Huang Xiaopeng, Guangdong Times Museum, 2021

In addition to the post-war deconstructionism, Arte Povera also had an impact on Huang Xiaopeng, who resonated with Antoni Tapies and Michelangelo Pistoletto in both material selection and performance direction. In some of the mixed media paintings on canvas, Huang draws on the surrealist approach used in some of Tapies’s works, combining symbols and lines more freely in an attempt to form a thematic relationship with the blankness of the image for more of a spatial sense of oriental religion. In Untitled (1993), Oh, Lord! Don’t Drop That Atomic Bomb on Me (1995) and Security Glass (1992), Huang moves away from the straightforward psychological projection evident in his collage works, and furthers his exploration of the material itself, particularly regarding “transparency” and “visibility.” At the opening of the exhibition, Huang’s student Du Zhongjian performed Break, a new work based on Huang’s Security Glass, in which the glass in Huang’s original piece was replaced with a mirror and shattered with a hammer on site, and then the shards were reassembled on the floor into a rectangle the size of the original material. Through the live performance, we can infer from the performer’s assembly-line-like movements, such as “smashing,” “sweeping,” and “calibrating,” that Huang’s use of the material of glass may have inadvertently alluded to the aesthetics of manufacture in an industrial society.

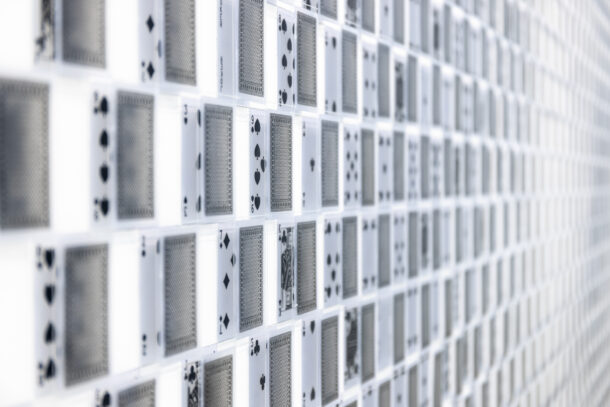

Huang Xiaopeng, Playing Cards (detail), 1996, installation (printed on plastic film), dimensions variable.

Exhibition version reproduced by Zhao Baochen

The exhibition presents a remake of the large-scale installation Playing Cards on the wall of the main gallery, with a deck of playing cards arranged to replicate a chess board. Each card is fixed face up on the wall, while a few centimeters away from the wall is a grid of fish wire, with the pattern on the back of the cards suspended in a translucent state. The artist offered a metaphorical explanation: “Feeling confused about my own identity, as well as the gambling culture in Chinatown, I became interested in playing cards. If you can see your opponent’s cards and do not have to make guesses, then the hand can no longer be played. I started to make a series of works related to playing cards to explore the bottomline of the game’s rules and its relationship with identity by transforming the backs and fronts of the playing cards.” In fact, such a metaphor is no doubt a simple technique applied visually like an optical trick, but it also reveals the artist’s assumption of the playing cards as part of the individual semantic structure. It is worth noting that the ambiguity presented in the sculptures is transformed in the artist’s subsequent multimedia works. Huang Xiaopeng’s experiments with concealment, reflexivity and multiplicity in these early works are crucial for understanding the media works he made after his return to China.

Huang Xiaopeng’s body of work, including installations, videos, and advertising posters, is seemingly serialized with robust spontaneity in the execution. The title often reveals the tension and conflict the artist had previously observed before the work manifests in the space. The artist’s iconic use of mistranslation, on the other hand, wraps the point of contention in humorous pop culture references. If mistranslation, to borrow words from Roman Jakobson, is an “organized violence committed on ordinary speech,” Huang’s deployment of it puts the chaotic cultural amalgamation in the global market into layman’s terms. While evoking imagery of Bruce Lee beating up white antagonists in The Way of the Dragon (1972), Huang’s Hit Me Baby One More Time (2010) links Britney Spears’s hit song to an inarticulate yet ambiguously somber exclamation about industrialization. The mismatching of cultures, thanks to mechanical and overly-literal translations, is reminiscent of the Dakou culture (translator’s note: the semi-illegal circulation of damaged foreign CDs and tapes that were imported to China as plastics) in the 90s, where a seemingly minuscule gap contains a dynamic system of cultural circulation across the globe. With such multiplicity in mind, Huang zeroes in on the tri-lateral relationship between popular culture, labor relations in global capitalism, and industrial cityscape with misplaced sound, moving images, and texts, poking fun at the discord in machine-translated terminologies. In particular, the artist conceptualizes and problematizes videos from commercial and popular culture by speeding them up, repeating, or playing them backward; he appropriates current events to highlight the tension between the labor and laborer in the global economy. Huang casts doubt on absolutism by subtly juxtaposing and overlapping various ideologies commonly found in an urban environment. His interpretations of different takes on society take on a diverse array of media, which speaks to the artist’s incessant contemplation of multiplicity throughout his practice.

Huang Xiaopeng, WHATDOYOUBELIEVE, 2019, outdoor billboard, dimensions variable.

View of DON’T KILL ME I’M IN LOVE!—A Tribute to Huang Xiaopeng, Guangdong Times Museum, 2021

Many of Huang Xiaopeng’s works borrowing advertising aesthetics, for instance, WHATDOYOUBELIEVE (2019), have grown out of, while tracing their roots to, his tendency for translucency in his earlier practice. Many slogans provocatively expose the alienating effects capitalism and production have on our spiritual world yet refuse to provide the artist’s solution that the audience would expect to find out. The answer to any of the questions Huang proposes, however clearly stated, is nowhere to be found throughout the show. Many of Huang’s portraitures, contributed by his former students, particularly, leave more questions than answers. These portraits, tackling subject matter such as masculinity, political identities, and pop culture, exemplify a one-sided love affair: although the artists have collected abundant raw material, they failed to regurgitate it back into circulation with any criticality. Such a fast and loose, almost amateurish, attitude can be viewed as part of the artist’s charisma in context. However, these themes, long controversial in the Western art world, had been consumed, digested, and finally become part of Huang’s life outside of his art.

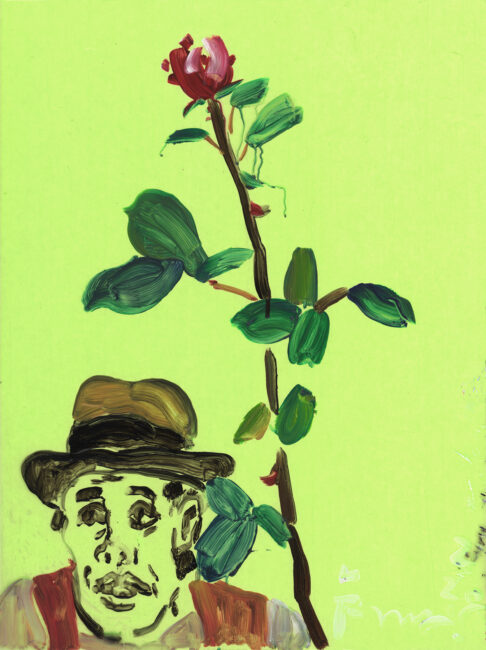

Lu Shan, A Portrait in-between Joseph Beuys and Huang Xiaopeng, 2021, acrylic on colored transparent plastic plate, 45.5 x 30.5cm

Leaving loose ends in his value system, Huang Xiaopeng opened up more space for himself as an art educator. In their works dedicated to their former mentor for the exhibition, Huang’s former students have worked with images without stressing their authorship—a reaction to the structural and conceptual transcendence in video editing. For instance, in Zhang Yin’s The Fifth Studio is a Self-contained Space within the System of the Arts Academy (2021), Hu Xiangqian’s Hint (2021), and Fang Di’s Marlboro Country (2021), the moving images reflect a reality specific enough to be meaningful yet not unique to any individual cases. The artists intentionally reject empathy through dramatization and opt for a subdued display of serialized moving images that guide the viewers through a conceptual reality.

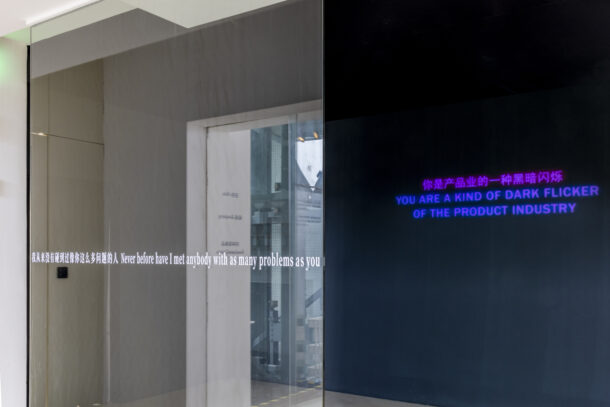

View of DON’T KILL ME I’M IN LOVE!—A Tribute to Huang Xiaopeng, Guangdong Times Museum, 2021

The two pieces that begin (and conclude) the show, Never Before Have I Met Anybody with as Many Problems as You (2003), and Only You (2009), echo a persistent tension between an individual and their environment. In the sense of alienation, Huang Xiaopeng seems to offer a prognosis for the psyche of his generation. In both of the pieces, individuals make faint remarks while surrounded by industrial and consumer products. The art begins with a question or a twinkle in the dark. In the face of overwhelming industrialization and the change of times, the artist, a pondering dreamer, stands no footing. As part of the vulnerable and serendipitous contemporary art world, artists often have trouble validating their existence and withstand misunderstanding by society at large. For Never Have I Met Anybody with as Many Problems as You (2003), Huang prints the title on a sheet of glass. Installed at eye level, the vinyl text interrogates the viewers as their gazes penetrate it, communicating and separating simultaneously. Only You is better known as the theme song of the movie A Chinese Odyssey. Huang’s Only You (2003) ambiguously projects the plot of the movie, where Monkey King, Bai Jingjing, and Zixia get tangled up in the web of fate, onto an unspecified subject and an industry for a less-vague consumer product. The work puts the audience to task, by juxtaposing and interrogating the past and the future, to re-evaluate what they believe to be the reality. However, the law of loss and gain is never consistent when put against a timeline. Cognitive dissonance seems to be the only constant in time.

Throughout his lifelong exploration of art and languages, Huang Xiaopeng had never deviated too far from his critical thinking of mundanity, labor relations, and cultural diversity. The artist showed sharp interpretation and clever intervention of the times he lived through. The exhibition catalogue includes a William Blake quote Huang had once quoted when he was younger, “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” It is clear to me that even back then, Huang had realized that art-making can never be bound to the logic of linguistics. Portraying the “real” is the ultimate pursuit of any form.

Claire Shiying Li is a curator and video producer based in Shanghai. She is now preparing a pan-cultural podcast program titled “41E78NYC.”

Translated by Zhiliang Zhao