The Aesthetic Transformation of Motion—A Dialectical Take on Sports and Contemporary Art

| November 20, 2024

When considering the relationship between athletics and art, we often think of sports like artistic gymnastics, figure skating, synchronized swimming, and div- ing, which are judged by aesthetic standards. We might also recall ancient Greek sculptures such as the Discobolus (c. 460–450 BC) and the Doryphoros (c. 450– 440 BC). Although athletes in these artistic sports perform in special attire and venues, and despite the aesthetic experiences they offer, these activities are still predominantly seen as sports. This perception is primarily due to their scoring and ranking based on performance metrics. In contrast, lifelike sculptures are viewed as art because they idealize aesthetics, form, morality, and ethics rather than realistically portraying an athlete or victor. They represent humanity’s ideal aspects, which do not exist in reality.

Sui Jianguo, Cloth Wrinkle Study—Anatomy, 1998

Painted bronze, 60 × 20 × 40 cm

Courtesy the artist

Beyond the philosophical connections between sports and art since ancient Greece, the two share formal similarities, particularly in the architectural design of museums, theaters, and stadiums. Both sports and art are removed from daily life, a distinction that has persisted throughout history and remains evident today; they require specific venues for participation and appreciation. Compet- itive sports need designated fields, and art requires specific spaces for viewing. Sports fields have defined boundaries, while art is confined to two-dimensional or three-dimensional forms. Both engage audiences and involve performance, regardless of whether the athlete or artist is present. However, even if we bring artistic sports into the realm of art, they cannot be considered art itself. This boundary seems inherent and essential, not just a result of post-Enlightenment knowledge classifications. In classical representations of sports in ancient Greek sculptures, we see a fusion of these two distinct languages.

In the 1990s, the Chinese artist Sui Jianguo created two sculptures named after the ancient Greek sculptures Discobolus and Doryphoros as part of his “Clothes Vein Study” series. Both sports and art in China began to modernize in the 1980s: China has sent national delegations to the Olympics since then, and the “National Sports Art Exhibition” has been held every four years. By the 1990s, artists frequently traveled abroad, blending distinct and contrasting Eastern and Western elements in their works. In Sui’s two sculptures, he placed Chinese-style Zhong- shan suits on the Western classical figures, integrating socialist realism with classical Western sculpture and creating a complex dialogue between Western classical culture and Chinese socialist culture.

In his earlier sculpture work, the artist’s physicality and individuality are fully present. However, after 1997, particularly in the “Clothing Study” series, Sui Jianguo deliberately minimized his bodily presence and distinctive artistic style, opting to recreate well-known classical sculptures. The final images of his works are not merely Discobolus or Doryphoros in Zhongshan suits, but rather new, symbolic forms. This suggests that Western classical sculpture and Chinese Zhongshan suits—classical sculptural language and socialist realism—are not separate but combined to create a new symbol. This symbol, in turn, is endowed with new ideology and public significance within its specific historical and social contexts.

Sui Jianguo’s works offer a unique perspective on the relationship between sports and art. First, they capture a moment of athletic movement and transform it into art. Second, they reinterpret a classical Western artwork as contemporary Chinese art. Two aesthetic transformations occur in this creative process: a sporting action becomes a sculptural image, and a classical sculpture evolves into a new cultural symbol. From a viewing perspective, audiences in various contexts generate diverse public discourses around the same body and motion, influenced by their cultural, social, and historical settings.

Huang Ran, Fake Action Truth, 2009

Single-channel video, 5 min 50 sec

Courtesy the artist

The appropriation, transformation, and deconstruction of original meanings in Huang Ran’s video artwork Fake Action Truth (2009) are particularly complex. In this piece, two male boxers in vintage attire spar in a dark space without making any actual physical contact. The sounds that the audience hears are not boxing-related but instead consist of male breathing sounds extracted from 1970s pornographic films. Sports like boxing and wrestling, as forms of popular culture, embody both sportsmanship and entertainment. They require high physical skill and showcase intimidation and strength through language and body movement. The performance of dominance and power in these sports becomes extreme— athletes display legitimate violence on stage, while the audience channels their own desires. The stage is vibrant with frenzied action, and the audience with clamorous voices.

In Fake Action Truth, Huang Ran uses modern boxing as a vehicle to explore appropriation and deconstruction. The boxers wear vintage clothing, engage in a match with fake, impotent movements, and juxtapose a violent sport with pornographic breathing sounds. The long kiss between the boxers at the end is ambiguously intimate, paying homage to virtues like shared humanity and friendship, reminiscent of athlete camaraderie after a match. This blurs the lines between violence and intimacy, much like how the Olympic flame obscures ongoing wars and conflicts.

Even the binary opposition in competitive sports appears nuanced in Huang Ran’s work. In competition, there are no complete adversaries and no absolute wins or losses; ethically, there is no absolute opposition between people, as violence and intimacy intermingle. In discussing sports, we often separate athletes’ thoughts, feelings, and actions, even though they are unified in a single body. We assume an inverse relationship between muscle and intellect, despite many sports requiring high strategy. Additionally, we tend to view athletes as bodies to be studied and improved, while coaches are seen as the brains overseeing these bodies. Huang Ran’s works bring together different materials through video, breaking down binary oppositional thinking and existing frameworks and balances.

Huang Ran, Turn Over, 2007

Single-channel video, 3 min 21 sec

Courtesy the artist

In Huang Ran’s video work Turn Over (2007), the camera persistently focuses on three pairs of identical twins playing basketball. The audience sees two identical teams competing against each other. The players cannot distinguish teammates from opponents, recognizing only their twin brother as their opponent. Similar to Fake Action Truth, there is no verbal communication, only the sounds made by the players. Deconstruction is omnipresent: the usual relationship between language and communication is absent. How much of sports communication is silent? How much of the interaction between athletes, and between athletes and coaches, is conveyed through actions? Typically, we see sports as a process of self-overcoming and defeating the opponent. But in team sports, achieving this involves cooperation with teammates and overcoming another abstract entity. In Turn Over, this cooperation and victory hit a deadlock: the players find neither partners nor opponents. This reflects the similarity between athletes and artists: both face abstract unknowns before entering the competi- tion or finishing a piece.

Beyond the issue of binary thinking, these works raise significant artistic ques- tions about imagery. Art is inherently visual, and much of modern sports viewing is mediated through images and video. Huang Ran’s pieces challenge the reliability of these images and explore how they, as a medium, shape our actions and behaviors. While Huang uses metaphorical rhetoric to pose this question, the artist Yao Qingmei’s performance video Fight Landscape (2021) addresses it through a formal language.

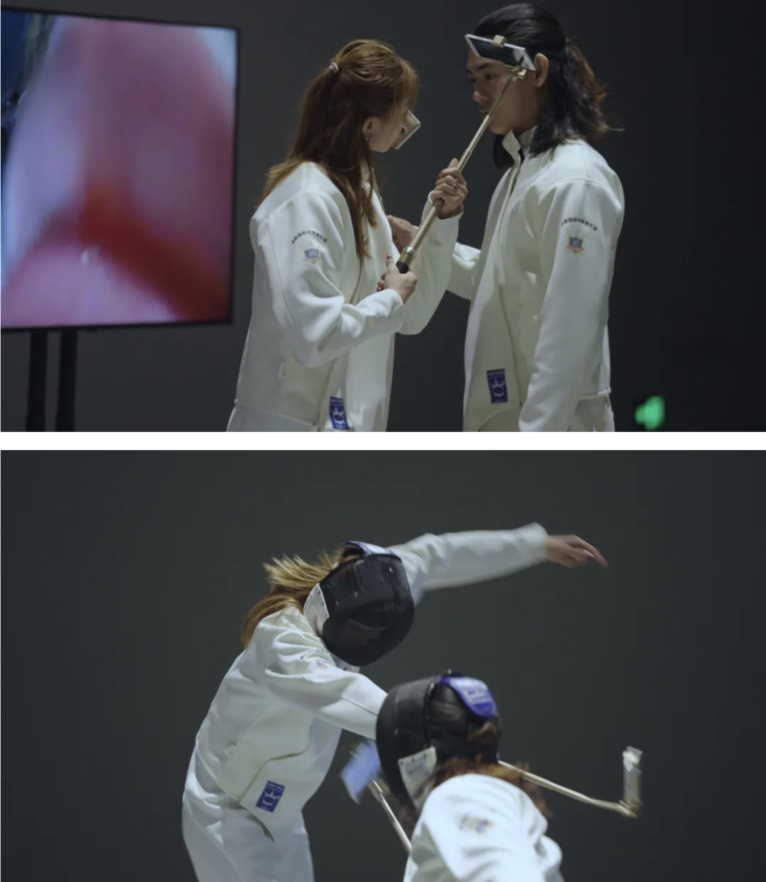

Yao Qingmei, Fencing: Landscape Fight, 2019–2021

Three-channel HD video, color, and sound, 18 min 46 sec

Courtesy the artist

In Fight Landscape, two fencers engage in a match where instead of swords, they wield selfie sticks. These devices record their actions, transmitting them in real-time to screens. The performance merges fencing with filmmaking; it’s a physical duel and an image contest simultaneously. This raises the question: Are they athletes or performers in this moment? What defines these dual identities? Is it solely their tools, the rules, or the venue, or are these identities more fluid than distinct? Returning to imagery, what visual languages define their actions and competitive relationship? How do images and sounds amplify the intensity of their movements? While sports typically emphasize physical prowess and self-overcoming, this work exposes the limitations imposed by our tools, highlighting how technology can restrict our physicality.

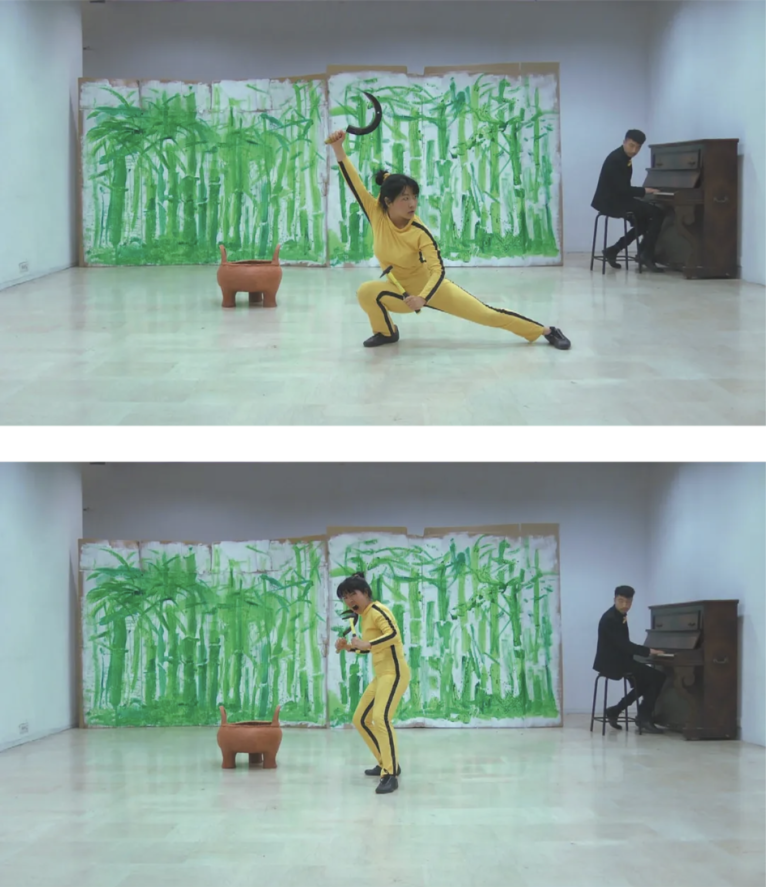

Yao Qingmei, Dance! Dance! Bruce Ling!, 2013

Performance video, 10 min 50 sec

Courtesy the artist

Yao Qingmei’s performance video Dance, Dance, Bruce Ling! (2013) explores further bodily limitations. The title references Dorothy Arzner’s 1940 film Dance, Girl, Dance, which tells the story of a girl striving on stage in New York’s urban culture while openly criticizing the male gaze in the arts. In Dance, Dance, Bruce Ling!, Yao incorporates cultural elements such as Bruce Lee, three-legged cauldrons, bamboo groves, sickles, and hammers into a dance and martial arts performance. While Arzner’s film is a narrative of success, Yao’s work presents a story that embraces failure, or rather a common state: it’s awkward, comical, and far from professional. However, it is precisely this form of performance that challenges the audience’s romanticized perception of athletes and artists as heroes.

We often perceive professionals in both sports and art as naturally gifted individuals, believing that years of training inevitably lead to success. While injury is an unavoidable aspect of competitive sports, failures or injuries are seldom discussed openly. Similarly, art history rarely recounts tales of failure. In our cultural and consumer narratives, sports are often portrayed as a path to achieving physical strength and excellence, while downplaying the inherent risks and potential for failure and injury. Sports education tends to prioritize winning over teaching how to cope with failures, emphasizing overcoming limits rather than acknowledging them.As spectators, we typically identify more readily with victors—the heroic image—rather than with a body that may be scarred or bandaged. Yao’s works spotlight bodily mediocrity, exhaustion, and failure, challenging the symbolic values assigned to the body. Through imperfect imagery and representations of imperfect physical forms and actions, Yao redirects our idealized per- ceptions to confront the reality of the limited physical body itself.

Hu Xiangqian, Reconstructing Michelangelo, 2015, performance

Courtesy the artist and Long March Space

Talent and the body have inherent limits, and skills require dedicated training. The roles of education and learning are crucial in both sports and art, where mastery is essential. These themes are central to Hu Xiangqian’s performance piece Remaking Michelangelo (2015). The work unfolds in two parts: one depicting an artist and an apprentice practicing gymnastic movements in a studio and engaging in discussions about art, and another showing a public performance. The master-apprentice relationship holds significant parallels in sports and art. In this piece, teaching and performance are intertwined, and dialogues between the master and apprentice explore what can be taught and learned, the training needed for professionalization, and whether education flows in a single direction. The work probes deeper, touching on underexplored issues such as the hierarchy in education and the top-down regulation of educational and professional pathways.

Hu Xiangqian, Stick Diagram—Painting, 2015

HD video, 6 min 45 sec

Courtesy the artist and Long March Space

Discussions of body and motion within specific contexts—such as the social historical context in Sui Jianguo’s works, the specific sports in Huang Ran’s works, or the virtual media and cultural context in Yao Qingmei’s works—highlight their distinct roles and meanings. However, in Hu Xiangqian’s work Stick Diagram— Painting (2015), specific contexts dissolve, causing body and motion to lose their references and be reduced to mere tools. The performance video captures the artist performing a stick routine, translating the stick’s path into spatial paint- ing, thereby blurring the boundary between action and painting. Here, body and motion lose their original meanings and become tools for measuring space— vectors of energy release and consumption. Similarly, in his performance Diagram for Speed (2011), Hu Xiangqian sprints between lights turning on and off, using his body as a tool to measure electrical speed. In both works, the significance of body and motion dissolves, transforming into representations of pure energy consumption and visualizations of the abstract.

Zhou Tao, E 6th St to Location One, 2009

Single-channel video: 16:9, with color and sound, 6 min 42 sec

Courtesy the artist and Vitamin Creative Space

Yang Zhenzhong, Cycle Aerobics II, 2005

Color inkjet print, a set of 8, 100 × 100 cm each

Courtesy the artist and ShanghART Gallery

Hu Xiangqian’s works redefine the body and its actions in a context tangentially related to sports, reducing them to mere tools. In contrast, Zhou Tao’s East 6th Street (2009) employs the body and its actions not only as tools to measure space but also as means to intervene in it. Generally, our bodies and actions are constrained by the spaces we occupy; in society, they are restricted by customs and conventions; in sports, by specific rules. East 6th Street seeks to transcend these constraints through unconventional actions. In this work, the artist and his friends navigate city streets in ways that defy pedestrian norms and physical spatial rules. They hold onto each other’s arms, move using points of connection on their bodies, or carry each other on their shoulders to move collectively. Some actions involve using another person’s body or architectural surfaces to move parallel to the ground or defy gravity. These instinctual yet atypical actions distort spatial perceptions and disrupt traditional notions of urban scaling between horizontal and vertical dimensions. Interestingly, these unconventional actions originate from bodily instincts but serve to alter the meaning of the actions themselves within everyday environments. Just as athletes push physical limits in sports, this work demonstrates that the body, even in everyday contexts, can be pushed beyond its perceived limits, transforming everyday spaces through bodily intervention.

The artist Yang Zhenzhong’s photography series “Cycle Aerobic I & II,” created in 1999 and 2005, features a couple riding a bicycle through parks and bustling urban spaces, performing synchronized actions reminiscent of routines in synchronized swimming and rhythmic gymnastics. This series integrates competitive sports into everyday contexts by liberating them from specialized venues and strict regulations, reintroducing them into social environments, human bodies, and intimate spaces. Consequently, confrontation turns into intimacy, and danger becomes an element of daily life.

The integration of sport into everyday life finds its most prominent contemporary manifestation in the rise of fitness culture. This culture inherits its attitude towards the body from sports, viewing it as a machine quantifiable through various metrics: height, weight, body fat percentage, bench press weight, marathon pace, VO2 max, step frequency, and more. This perspective allows us to use artificial tools to monitor physical performance, uncover our body’s secrets, and determine its predispositions—whether for muscle gain, long-distance running, or sprinting. In this context, the body becomes an experimental object, with efforts focused on surpassing current limitations. On one hand, we advocate against doping for fair sportsmanship, yet on the other, we employ medical and scientific methods—ranging from energy drinks to advanced equipment—to push physical boundaries. We simultaneously harbor concerns about the potential alienation of the body while applying various machines and energy substances to enhance it. In artistic creation, the mind may draw on influences like Dionysian fervor, drugs, and machines, while in competitive sports, the body navigates ethical and moral boundaries.

However, despite the myriad benefits that fitness promises, consumerism has driven this form of exercise towards the commodification of the body. This phenomenon has shaped a fitness culture oriented around consumption, giving rise to an entire industry advocating health foods, beverages, scientific equipment, and specialized attire. Consequently, fitness has increasingly detached from genuine health, instead becoming inseparably linked with image, fashion, and sexual allure—a commodified version of “health.”

Fitness has evolved beyond its original purposes of exercise, leisure, or relaxation, transforming into a rigorous discipline focused on the body. This shift reflects how our pursuit of the ideal body, akin to the perfected forms depicted in ancient Greek sculptures, has permeated everyday life. The ideal has transi- tioned from being an object of admiration to becoming a daily goal and lifestyle— a continuous investment of time and effort. Moreover, this ideal no longer merely signifies aesthetics; rather, beauty itself is now portrayed as an achievable reality, influenced by prevailing popularity standards.

The individual body faces collective cultural pressures, now intensified by the internet and its associated technologies. Individual exercise routines have been digitized, with physical actions migrating to virtual realms on electronic interfaces. Our environment is constantly shaped by the internet, thrusting individu- als into vast social spheres. Fitness communities and live streams not only foster emotional connections through exercise but also foster potential competitions.

Li Ming, ME I WE, 2015

Installation: video, sound, text, light, and audience

Dimensions variable

Courtesy the artist and Antenna Space

This contemporary cultural phenomenon is precisely what the artist Li Ming unveils in his video installation ME I WE (2015): the individual “ME” in front of the screen merges into a collective “WE.” However, as depicted in the marathon scene with crowds surging, the individual is simultaneously dissolved into the group, where only relentless and accelerated running allows for personal distinction. While traditional media may have facilitated individuals entering broader collective spaces through exercise imagery, the interface-based society formed over the internet continually compresses individual space. It molds the individual body and refines specific actions through mediated images.

These works from the past decades of Chinese contemporary art illuminate vari- ous facets of the aesthetic transformation of motion in art, highlighting the parallel yet distinctive relationship between sports and art. Both traditions pursue ideal states, embodying the union of body and mind, actions and postures within specific contexts, while their development and dissemination through media are influenced by political and cultural environments. In an era and society marked by diversity, sports and art manifest not as religious forms but in visible, tangible, and practical ways—human expressions in essence. They provide a comprehensive symbolic system that allows us to transcend fragmented realities. Through practice, observation, and imaginative exploration of future possibilities, sports and art offer a transcendent interpretation of our current reality.

*This article is adapted from the author’s speech at the second lecture of the “Motion and Body” serial symposium at the CAFA Art Museum in 2022.

Luan Zhichao is a prolific writer and translator in the fields of visual arts and cultural studies. Her translated works include The Afterlife of Images: Translating the Pathological Body between China and the West, The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood, and the Mind-Baby Problem, and Susan Sontag: The Complete Rolling Stone Interview, among others.

Translated by Pan Min