The Flesh as an Inside-Out Jacket: Body and Illness in Zhang Peili’s Work

| April 11, 2025

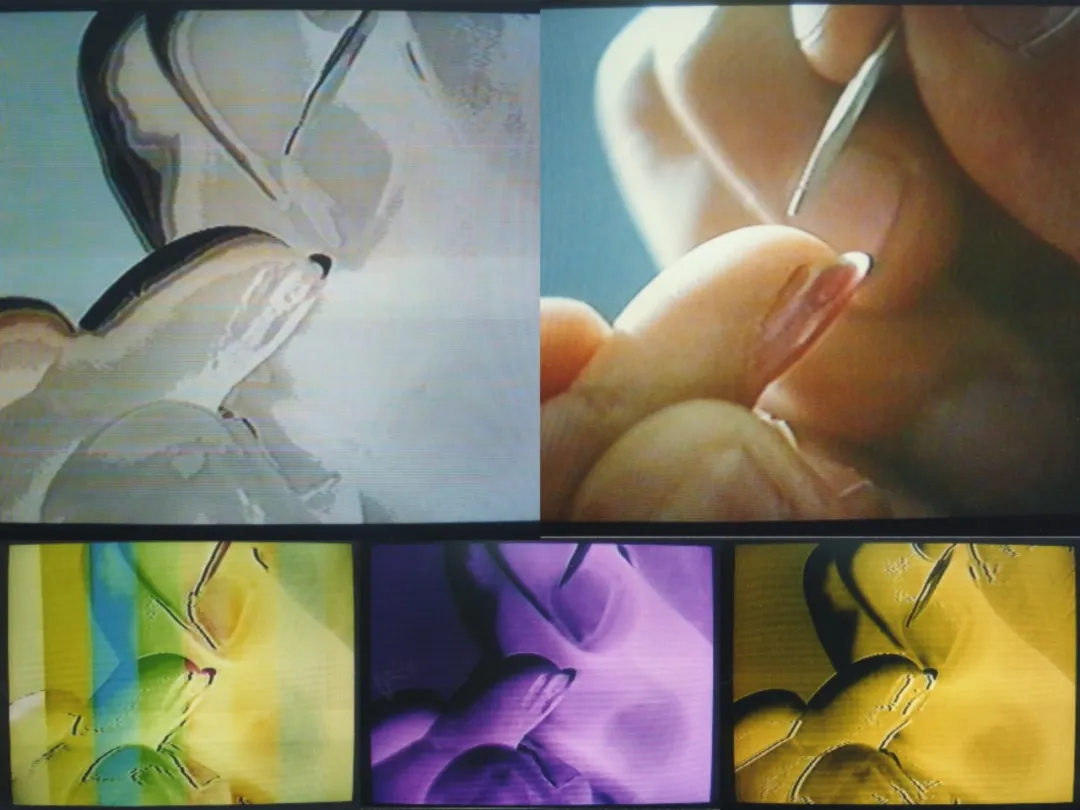

Zhang Peili, Assignment No. 1, 1992

Video installation, 13-14 minutes

All images courtesy of the artist and Taikang Art Museum

“My own flesh and blood to rebel!”

—The Merchant of Venice

Let’s start with a joke, because there is a strange way of short-circuiting here: for Shakespeare’s Venetian merchant, Zhang Peili’s art universe might be a nightmare. Let me explain–as you may remember, in The Merchant of Venice, the moneylender Shylock demands that our protagonist Antonio pay his debt with a pound of his flesh. In order to get his own back, Shylock puts on a show of impartiality in court, demanding that the contract be honoured “to the letter” and refusing to accept even double compensation. Since the contract was indeed worded this way, this put the protagonists in a difficult position. However, they eventually found a way to turn the tables: instead of rejecting it, they doubled down on Shylock’s principle. They argued that Antonio must not only pay Shylock a pound of flesh, but also an exact pound of pure flesh, not a single ounce more or less. Similarly, it must not lead to the person shedding any blood, otherwise Shylock would be found guilty. This impossible task then forced Shylock to admit defeat.

The conflicts in this comedy unfold around the ontological question of “law”. Shylock, the greedy merchant who paranoidly asserts that “The law shows no mercy”, is in fact insisting on an extreme rationalist position. When he exploits this position, “legal facts” replace reality. What he deliberately ignores is that the law is merely a regulatory façade, and beneath it there exists a chaotic, full of exceptions, living reality, the texture of which cannot be replaced by legal provisions. His opponents spotted the flaw in this position and employed a defence strategy of beating someone at their own game—since Shylock demanded a purely rational legal judgement, then, he would only get a piece of flesh that was also purely rational.

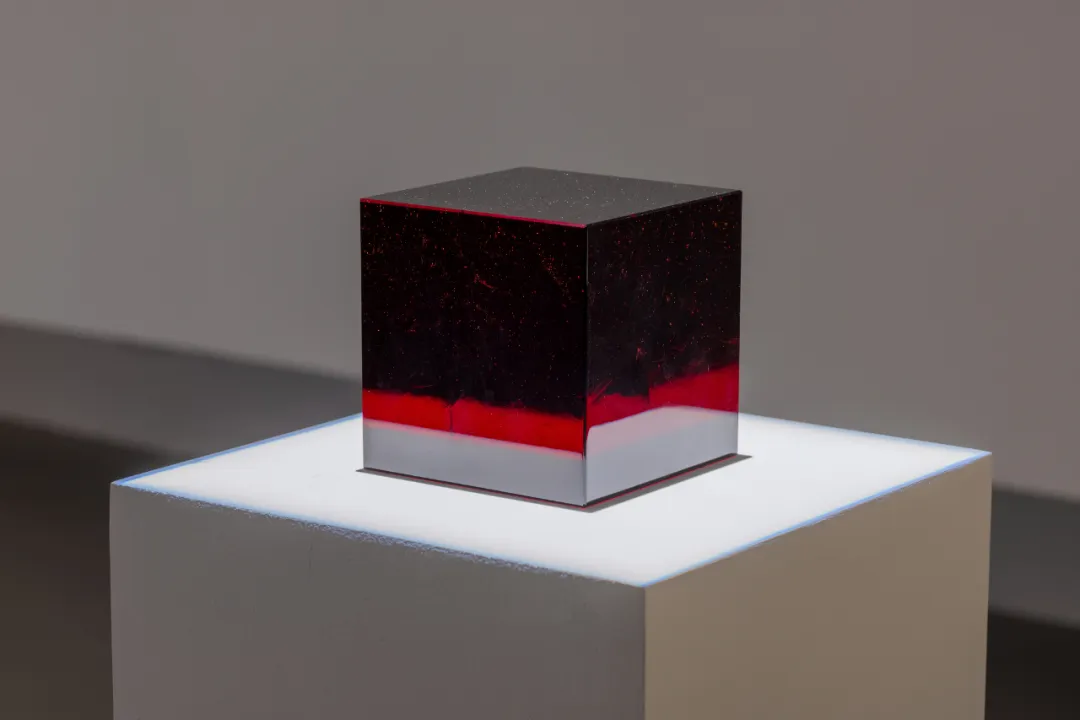

Zhang Peili, Total Fat Volume, 2019

Siena yellow marble, 21 × 21 × 21 cm

© Taikang Collection

View of Zhang Peili’s solo exhibition “2011.4.27—Permanent”

2024, Taikang Art Museum, Beijing

Photo: Yang Hao

The punchline of the opening lame joke was that what Shylock could not find in reality–a piece of purely conceptual flesh—would appear in Zhang Peili’s art universe. In the artist’s recent solo exhibition “2011.4.27—Permanent”, there are three installation works entitled Total Water Volume (2019), Total Blood Volume (2019) and Total Fat Volume (2019). The first is made of colorless, transparent artificial crystal and resembles a pool of water in an irregular bowl-shaped container, although the container itself is no longer visible. The latter two are both presented as regular cubes. In terms of material, Total Blood Volume is made of translucent artificial crystal with a dull reddish color, while the Total Fat Volume is made of marble with a delicate tinge of soft yellow. It is easy to see from the titles that these three works attempt to visually represent the total volume of a certain substance in the human body. Leaving aside the fact that these are merely artificial body fluid, blood and fat, everything can be said to be exactly as Shylock would demand—“pure” pieces of flesh, blood or water, and therefore certainly become Antonio’s disaster. What he was betting on is exactly the non-existence of such blood and flesh. According to Antonio’s belief, the human body should be a continuous manifold from which we cannot abstract any universal elements or purify anything homogeneous. As a result, the body will always be an elusive and ambiguous object. The law is powerless against it, as legal provisions cannot be applied with precision. Or to put it in the words of Giorgio Agamben: What Shylock demands is the absolute application of the law without exception. Yet, for the law, life can only exist as a total exception. Antonio’s counterargument relies precisely on demonstrating that, in the face of the infinite texture of reality, the law is utterly powerless. The contract that Shylock holds is ultimately unenforceable. We cannot really require a pound of pure flesh without “a shred of fat”—in the novel Water Margin, Lu Da makes the same unreasonable demand as Shylock to Zheng Tu. Soon everyone realizes that it is just a provocation and his demand could never be met. However, Zhang Peili literally makes it happen. The pure rational law becomes the reality in his art universe. We see individual body components being summoned and then stuffed into a Cartesian cube, a cube in which the measurements are equal along every dimension. For example, Total Blood Volume is a blood cube measuring 13 cubic centimeters. This is not about representing blood in terms of blood volume, but blood volume in terms of blood. Similarly, popular science articles often include the common knowledge that “the total amount of iron in the human body could make a 7-centimeter-long nail,” or that “the fat in the human body is enough to produce seven bars of soap” and so on. Interestingly, in none of these examples, including Zhang Peili’s 13×13, is a real, specific quantity with decimal places given, but rather a very suspicious integer. The artist has an instinctive desire to keep the data of the cube as concise as the cube itself. It can be said that the noumenon of the work Total Blood Volume is not “blood-fluid,” let alone “blood,” but a value related to blood, in other words, the highest degree of abstraction of “blood.”

Zhang Peili, Total Blood Volume, 2019

Artificial crystal, 13 × 13 × 13 cm

© Taikang Collection

View of Zhang Peili’s solo exhibition “2011.4.27—Permanent”

2024, Taikang Art Museum, Beijing

Photo: Yang Hao

What the artist presents is not a body, but a body that has been violated by a rational order. Apart from its similar color and matching measurements, the cube has actually lost all the substantive content of blood—associations such as flow, penetration, circulation or survival have disappeared. But what is even more interesting is that the artist even blocks its connection to death. In visual instinct, the phenomenon of “blood leaving the body” is almost equivalent to the signal of death, and it is precisely because of this that humans are sensitive to large areas of red. However, in Zhang Peili’s work, we see lifeless blood that has completely left the body, but this does not evoke an image of death. On the contrary, since the connection with life is broken, its connection with death disappears correspondingly. Zhang Peili’s mysophobic “blood extraction” does not come at the cost of life, but at the cost of fundamental existence. The blood that can be summoned without effort is false from the start. It never gives life to the body. The proof is that it does not disperse after leaving the body, does not splatter as a stain or precipitate to form livor mortis and thus mark the existential scene of a life. Conversely, it is even more under control. The blood is arranged in neat arrays for inspection, as if to suggest that the human body is, after all, just a machine. Before we are given life, all the parts of our bodies already exist, they have just not yet been assembled. They are just prefabricated parts. And Zhang Peili’s work simply reduces the body to the sum of these parts. Everything can be quantified because everything is produced in a standardized manner from the beginning.

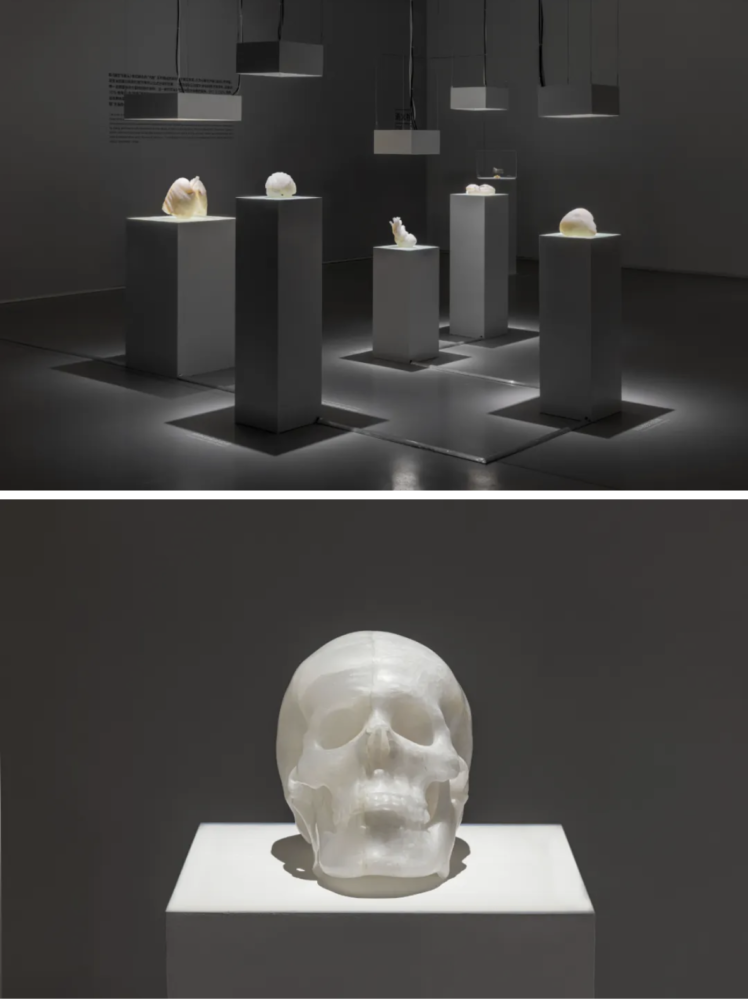

View of Zhang Peili’s solo exhibition “2011.4.27—Permanent”

2024, Taikang Art Museum, Beijing

Photo: Yang Hao

Zhang Peili mentioned his family’s medical background—his mother was a midwife and his father taught anatomy at medical school—and said that it had determined to a large extent the artistic style he has today. However, compared to the apparent inheritance of a family’s career, there is another difference that is more worthy of attention: from father to son, “anatomy” presents itself as two completely different types of work. The former is concerned with the body as the Real, which is characterized by chaos, disorder and decay. In legal terminology, such a body encompasses an infinite series of exceptions; in chemical terms, it is always impure; and to use Zhang Peili’s own words, the real body is never “hygienic.” In contrast, the artist’s anatomy is aimed at the conceptual body, which is more like a database or a matrix; or, to borrow a recent concept, it is more like a metaverse version of a body, a “cloud body,” because everything is quantified and virtualized, then stored in it. Any part can be called up at any time and presented individually, without any noise. In Zhang Peili’s work, the disagreement between Antonio and Shylock is manifested in a father-son relationship, an inheritance relationship—the father has to face reality, while the son only needs to face the father’s laws. Regarding the former, it might be a good idea to read a passage written by the Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgård at the beginning of the first volume of his famous book My Struggle (Min Kamp) :

For the heart, life is simple: it beats for as long as it can. Then it stops. Sooner or later, one day, this pounding action will cease of its own accord, and the blood will begin to run towards the body’s lowest and weakest point, where it will form a small lump, visible from outside as a dark black congested patch on ever paling skin…

The Real of the body is a “Body without Organs”1 (B.w.O.), a form that harbors an exceedingly rich network of internal connections, to the extent that internal distinctions become secondary. What matters is the connection between the heart and the blood, not their separation. Instead of claiming that the body is composed of distinct, autonomous organs, it would be more accurate to say that each part of the body is merely a reflection of the functions of other parts. Blood manifests the function of the heart, and once the heart fails, the reaction of the skin becomes an expression of the loss of control over the blood. Ultimately, this may even visually materialize as a pattern of disorder, known as livor mortis.

But the heart made by Zhang Peili never beats. On the contrary, as we have already seen, the internal distinctions of the body is the First Principle of Zhang Peili’s work. It presents itself as a system of general differences—a system consisting of names. Here one might even say, it is an administrative system that satisfies all the imaginations of Logos about the flesh. Any body composition can be retrieved from the system according to its function, either vertically or horizontally. We can not only divide the body qualitatively according to its material composition, and thus find blood or water in the “lines” of the circulatory and lymphatic systems, but also define it territorially according to its organs, thereby identifying “blocks” such as the heart, liver, or large intestine. Bureaucratic technical terms are appropriate here, because no matter through which classification method, what we get are always independent institutions with specific powers and responsibilities.

View of Zhang Peili’s solo exhibition “2011.4.27—Permanent”

2024, Taikang Art Museum, Beijing

Photo: Yang Hao

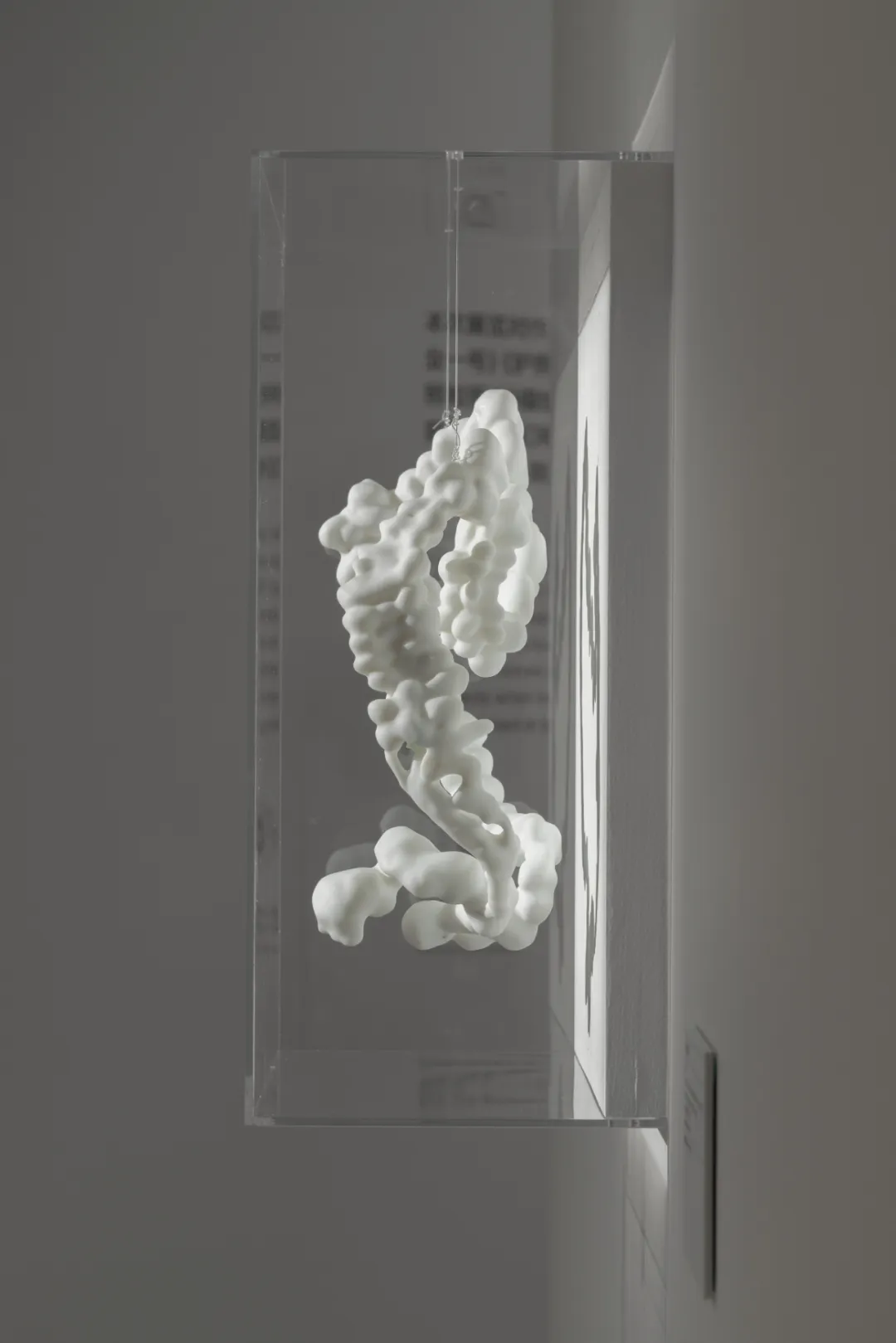

This is particularly evident in Zhang Peili’s organ model installations. In these works, each human organ is made of marble. The artist rather fundamentalistically chooses Carrara white marble from Italy, a stone known by the name of the classical master Michelangelo. What could be more representative of rationalism than such high-end marble? In the history of ideas, this material itself has long since become a classic metaphor, representing Kant between empiricism and idealism, and Einstein between quantum mechanics and the theory of relativity. Whenever chaos against order, it then appears and is used to underpin a rational cosmology. If a rationalist world can be constructed from a symbolic material, then marble is undoubtedly the most suitable building block. In Zhang Peili’s case, it implies an absolute generality arising from absolute distinction, that is, absolute uniformity and absolute indifference. In other words, whether it is the heart, liver, intestines or stomach, they are all atomically composed of the same thing. These organs remain absolutely identical in terms of material, space and even time—precisely because of its consistency in the temporal dimension, the marble is eternal. The reason these marble organs are different is only because an external voice has imposed different regulations on them. It is only the Logos that discerns them from one another. In other words, what we are doing here is merely following the unreflective, everyday usage of language to understand the body. However, for the body itself, the differentiation that distinguishes it implies a transcendent power beyond the body itself. Indeed, it would not be an exaggeration to say that these organs are “interpellated” (interpellé) into existence. At this point, Althusser’s claim naturally comes to mind: contrary to the anatomical content of his father, Zhang Peili’s anatomy is political. It is, in its very constitution, equivalent to an ideological apparatus, regardless of whether it operates smoothly or is already falling apart.

View of Zhang Peili’s solo exhibition “2011.4.27—Permanent”

2024, Taikang Art Museum, Beijing

Photo: Yang Hao

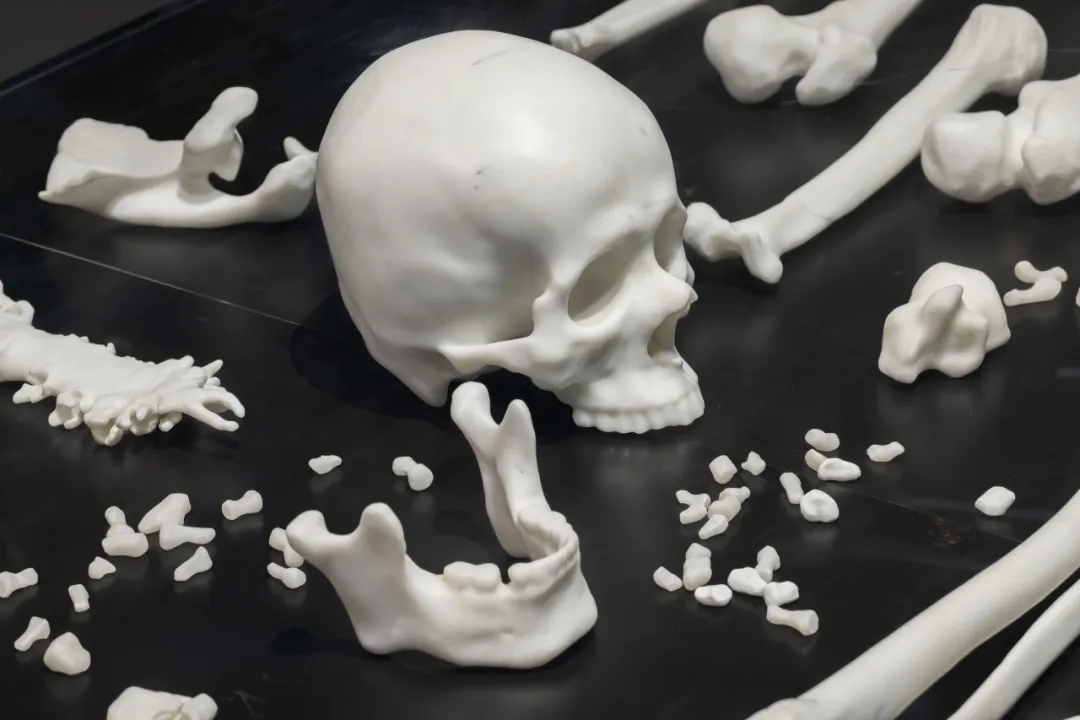

In Bones and Organs (2019), we see nothing less than the most standard and straightforward “Organs without Body”2 (O.w.B.). Rather than an anarchic ruin of the body, what we have here is a purely structural diagram of the body, a mere form, not the debris of a dissolved entity. For, let us not forget, these scattered and floating organs have not only been cut off from their outside connections, they have also been emptied from the inside. It is precisely the noble Carrara marble that has emptied them. The inside of organs is, to a great extent, far more important than the outside. The vocation of organs is to carry and transport matter. Now, having lost both the outside and the inside, they can no longer contain anything or be contained by anything: the blood vessels no longer contain blood, the intestines no longer contain faeces—the blood has been diverted to another work, and the excrement is not acknowledged to have existed. In another work, 19-B004 (2019), a complete human large intestine is also made of white marble and is solid. Can it be said that the excrement in the large intestine is also represented by that clean and elegant stone? This can be considered the ultimate “hygiene,” although it also comes with a subtle anxiety: from now on, we will not be able to tell the difference between marble and faeces. For Zhang Peili, representing the body entails disinfecting it, permanently negating its metabolism and circulation in order to obtain an eternal and immortal body—even if it comes at the cost of ultimately losing the body itself.

Zhang Peili’s body is a political utopian body, such a body carries with it a profound risk. Because we have almost reached this point: discovering that these rational and eternal body organs have already taken the shape of a high-quality commodity. They seem to perfectly meet Shylock’s standards, ready to be weighed and priced by the pound. As previously hinted, if we overlay Nietzsche on top of Leibnizian extreme rationalism, and then overlay Marx once more on Nietzsche, the underlying tone of the matter becomes apparent. Is this differentiation and quantification of reason not precisely the logic of valorization? And is the dazzling display arrangement found in works like Bones and Organs or All the Bones of the Body (2019) not evocative of the distinctive presentation of commodities—be it the jewelry on display in a showcase or the various cuts of meat laid out in a butcher’s shop?

View of Zhang Peili’s solo exhibition “2011.4.27—Permanent”

2024, Taikang Art Museum, Beijing

Photo: Yang Hao

However, there is another context that also points to the necessity of quantifying the body: the medical context. This becomes even more apparent if we look at it in conjunction with other works, such as Data on Lungs, Gallbladder, Common Bile Duct, Arteries, Pulmonary Arteries, and Pulmonary Nodules (2019) or Image Report (2019). Compared to Total Blood Volume or Total Fat, here we get more, excessive values. And unlike the former, here values are nothing more than values; they do not manifest as objects but are deliberately and rigidly arranged on paper. In Image Report, we see the original scene of Zhang Peili’s “extraction” of the body—the kind of extraction that can externalize the contents of the body without showing any damage. In fact, it is a variety of medical examinations. The reason it is harmless is because that is the dream of medicine; the reason that blood, fat and water or the heart, liver and stomach can be abstractly extracted is also because they are the subject of medical examinations, or rather, they are not blood, water or the heart, but just indicators on a medical examination report.

We therefore have to partially revise most of the comments (and perhaps the artist’ own comments as well): what is presented in the exhibition is not anatomy, but rather a huge medical examination report. The difference between anatomy and medical examination is both subtle and decisive: the former implies death, destruction, and therefore also life, while in the latter we do not see any body, merely a simulacrum of the body over and over again from beginning to end.

Zhang Peili, 30×30, 1988

Single-channel video, 32 minutes 9 seconds

In a way, we have thus liberated Zhang Peili’s body from the territorial machine. Now, it can neither be said to be a purely unrealistic virtual archive, nor a poor body that has been monetized, at least not entirely. This is because, although medical examinations only provide copies of reality, they contain a great deal of concern for the real body. Furthermore, medical examinations are not intended to sell the body. Of course, it could be argued that medicine itself is a form of politics imposed on the body. But in any case, this technique of governance points to a more dramatic point: illness. In the late 1980s, the hepatitis virus that ravaged Hangzhou deeply affected Zhang Peili. At that time, China’s public health system was undergoing transformation, and the artist more consciously seized the metaphor of illness. This is where everything converges. All the efforts to abstract, purify, and simulate the body, and then to purify, disinfect, and make it “hygienic,” are all aimed at fighting against illness. All these efforts are an attempt to prove that we have full supervision and control over our own bodies, that the body operates within the framework of our rationality. The illness has no opportunity to infiltrate. It could even be said that mysophobia is at play from beginning to end. In this sense, 30×30 (1988), Wei Zi San Hao (1988) and the subsequent organ installations all reflect the same concern. Gluing back a broken mirror or cleaning a chicken are creative actions that could be considered childish, but they also reveal a unique hysterical tone. In the former, the artist attempts to restore disordered matter to a state of order, but the disorder itself was caused by him. We have already seen him awkwardly breaking the mirror at the beginning of the video—in fact, are the two multiplied integers “30” not a harbinger of the cubes that will come later? When the artist tries to cast blood, body fluid or fat into cubes, he may constantly recall the initial mirror surface. From this perspective, the simplicity of the blood cube comes from a real industrial standard, and “13” sounds more like an echo of “30.” In the latter, by imposing the human act of “bathing” on the animal, the artist shows on the one hand that the chicken is unsanitary, and on the other hand, he implicitly admits that this perception of uncleanliness is itself only his subjective wishful thinking. The desire to obtain a hygienic chicken, a cubic meter of pure blood, or to extract a pound of human flesh from a debtor like it were from an ATM is essentially the same thing.

Zhang Peili, (Wei) Character No. 3, 1991

Single-channel video, 24 minutes 45 seconds

Through illness, we see a new and promising possibility for referring to the body. This is because contemporary art has already provided more than enough expressions regarding the body, yet they always fall short of expectations. As Zhang Peili’s solo exhibition originally presented, if we unthinkingly identify every body-related image as the body, then what we end up with is not so much a number of possibilities for the body as all the impossibilities of the body—whether it is the volume of flesh and blood, organ replicas, medical examination data, or plastic gloves used as medical equipment, they have all moved far away from the body and too quickly become a general description of the body. In this sense, too, the emergence of identity documents (Passport and Visa Endorsement, 2016; Password, 2019) is a matter of course. Because in essence, those materialized organs, in the same way as ID numbers, are all just indifferent determinateness (gleichgültige Bestimmtheit) of one’s own body. Everything is just a code, and is nothing more than the logical result of using various types of rhetoric in turn on the body—organs as synecdoche, gloves as metonymy, documents as metaphor, etc. If, as Zhang Peili himself says, this exhibition embodies a process of “finding oneself,” then we should add: this process is accomplished through a method of elimination. Because this search is destined to be fruitless, with every attempt ending in a dead end. Most contemporary art exploring the body also ends in failure in this way. Those displays of gender, the countless poetic transformations of organs, and the self-abusive attempts to discipline the body in the Foucaultian sense all miss the point—the body with flesh and blood, no matter how bloody the scenes they present are. We are like the scientist in that popular philosophical metaphor—someone who has mastered all knowledge of color but is color-blind themselves.

Zhang Peili, 30% Fat, 70% Lean Meat, 1998

Video recording installation, 7 minutes 53 seconds

Artist’s collection

At the very least, it is necessary to recall a phenomenological perspective and recognize that the first-person body is experienced from within rather than from without. It is not about the shape of organs or the depth of wounds but rather signifies the delimitation of perspective, the point of reference for spatiotemporal shifts, and the possibility of pain and pleasure. In short, from the inside looking out, the body is everything that is non-body. Just as, from the inside looking out, the focal length of a camera lens is not experienced as its physical length but as the degree of distortion present in the resulting image. We come to embody the “body” of perspective through the effects of images. The body is like a jacket worn inside-out upon us. The exploration of the body is a test of incarnation (becoming-flesh), one that can hardly be accomplished by merely displaying certain images of the body. What is called “the body with flesh and blood” is not an objectified body, nor is it the reified flesh and blood that resembles raw ingredients. Rather, it is a body that suffers and endures, a body that lives and dies.

Therefore, although every attempt to “find oneself” failed, this failure itself was fixed, because, as mentioned earlier, the illness served as a meeting point to bring it all together. The obsessive need to be clean—this transcends all contemporary discussions about the body. In this way, all of Zhang Peili’s failures gain a perspective of totality. They are no longer just a bunch of individual failure cases, as we usually see, the blind man’s repeated attempts to feel the elephant (thus implying that such failures will continue to happen in the future)—they are no longer just normal failures, but can be aggregated and reflected as an ultimate failure. We realize that it is ultimately impossible to bridge the gap between subject and body, also to reconcile Shylock and Antonio. It is precisely because Zhang Peili refers to the body in such varied ways that the inevitable impasse becomes all the more obvious. This time, however, the impasse itself also attains embodiment: it is the illness.

It may be worthwhile to recall Nietzsche’s famous perspectivist assertion about illness and health. Nietzsche emphasized that, despite suffering from a range of chronic illnesses, he nevertheless considered himself healthy. In fact, it was precisely because of these illnesses that he felt an even stronger sense of his own health. The more the illness assailed him, the more it revealed itself as an external calamity, and the more justified he felt in declaring: “I am myself, and the illness is the illness.” Proust expressed a similar idea in a more concise manner: “The sick feel closer to their own soul.” In a similar vein, a will plagued by mysophobia and hypochondria ultimately disguises the soul as its own body, thereby producing an absolutely hygienic, imaginary flesh. Isn’t this precisely the same process at work? Hidden behind every failure of embodiment in Zhang Peili’s bodily imagery lies an eternal unease—and this unease is none other than illness itself. Susan Sontag once noted Kafka’s peculiar phrasing when referring to his tuberculosis in a letter to a friend, where he remarked that “my head and my lungs have reached an agreement without my knowledge.” The critical issue is that, no matter how many pathological images Zhang Peili produces, this conspiracy may still persist. We could even bypass all of Susan Sontag’s reflections on illness and arrive directly at the heart of the problem: the ultimate metaphor for illness is the body itself. Or, in the context of this particular example, it should be reversed: the ultimate metaphor for the body can only be illness. Perhaps only illness can simultaneously objectify the body and preserve its first-person embodiment. Because of dysfunction, we become aware of our body; we no longer inhabit it seamlessly as a natural extension of our consciousness but experience it as an object before us. Yet, the inescapable pain of illness reminds us that this cannot be anyone else’s body, for pain cannot be shared. On the other hand, an absolutely pure body is fantastically delivered as an ideal, displayed on the wall. This part of the content remains suspended in the mode of the purely virtual, captured on canvas, with some depictions so extreme that they could not even be included in the same exhibition, otherwise it would be too cruel. Take, for instance, the midsummer swimmers—who are, themselves, nothing more than geometric figures—swimming and resting in pools composed of pure geometric forms, immersed in the clarity of disinfectant water. After the failure to acquire ownership of the body, to catch a glimpse of this “ideal body”—like quenching one’s thirst by gazing at plums—is undoubtedly a desperate thing.

Notes:

1. In Gilles Deleuze’s terminology, the distinction between different organs is merely external. For Deleuze, “organs” are nothing more than artificially demarcated zones, and viewing the body through this mode of partitioning results only in a mechanistic understanding. He advocates for the dismantling of these fixed divisions in order to recognize the body as a full, dynamic, and fluid entity. Deleuze’s use of the term “body” is originally broad in scope, referring not only to biological bodies but also to any organized multiplicity. However, in the context of this article, the term is to be understood in its narrower sense.

2. “Organs without bodies” is a paired concept proposed in relation to Deleuze’s notion of the “Body without Organs.” Slavoj Žižek, in his book Organs Without Bodies: On Deleuze and Consequences, highlights this concept as part of his critique of Deleuze’s later philosophy. According to Žižek, the dimension that distinguishes things cannot be completely eradicated; it ultimately manifests as a conceptual “minimal difference.” This article adopts a somewhat negative usage of the term. For instance, when all the organs of the human body are transformed into marble sculptures and presented in isolation, it implies that the artist, whether intentionally or unintentionally, ignores the internal differences within the body. Instead, he places greater trust in the codification of the body by everyday language—such as heart, liver, or intestines.

Translated by Zhou Jiayu